In most areas of creation, competition often drives innovation, especially when legislation is set in place and specific rules are enforced to be followed. When it comes to cars, competition births innovation but can also lead to regression when too many rules are set in place for one reason or another.

For example, there was a period in Japanese automotive manufacturing history where an unspoken understanding among carmakers led to a unique form of self-regulation in the Land of the Rising Sun as far as cars go.

Known as the Japanese Gentlemen's Agreement, it focused on horsepower and top speed limits for domestically sold vehicles. This agreement, which took place during the late 20th century, primarily the 1990s, saw all major Japanese automakers cap their vehicles' maximum horsepower and top speeds to specific thresholds.

Specifically, all Japanese cars sold in the island country between 1988 and 2004 had their advertised powertrain outputs capped at 276 HP (280 PS). There was no government set of rules to enforce this odd agreement, and plenty of sports cars unofficially broke it, but then again, this is the very definition of a 'gentlemen's agreement.'

With that in mind, I decided to explore this intriguing agreement's origins, implications, and eventual dissolution, which coincidentally happened exactly two decades ago.

The Japanese Gentlemen's Agreement emerged informally among Japan's leading auto manufacturers at the end of 1988, and it included legacy brands like Toyota, Honda, Nissan, Mazda, and Mitsubishi. In theory, it was rooted in a combination of safety concerns, insurance costs, and a desire to avoid potential government-imposed restrictions.

By the late 1980s, Japan's bubble economy had led to a surge in high-performance, technologically advanced cars. As speeds increased, so did concerns over road safety and the potential for regulatory backlash.

The Japanese economic miracle that had started after World War II was also hurling toward a sharp end, which probably precipitated the need for a form of self-regulation in some areas of the industry.

In other words, this method of self-restraint, also known as a strong cultural concept called 'jishu-kisei,' was seen by many as a blessing instead of a killjoy. Oddly enough, the 276-horsepower threshold was rooted in a slightly older rule, which was stipulated over a decade earlier by the Japan Automobile Manufacturers Association (JAMA).

In the mid to late '70s, road fatalities in the Land of the Rising Sun had started to increase exponentially, and many saw this as a result of a growing number of sports cars that were getting faster and faster.

That is when a nationwide ban on cars that can go faster than 112 mph (180 kph) was implemented, regulated by a speed governor installed from the factory in every JDM vehicle built since then.

The '276-horsepower' limit on advertised output came on top of the speed limit rule in 1988, but it was more of a handshake than a signed contract.

Some say these limits were set to promote road safety and offer insurance companies a level playing field, making high-performance cars more accessible to the average Joe.

Others believed that the output limit was introduced simply to avoid a power race that would eventually be negative for both carmakers and consumers.

For example, without the limit, if Nissan introduced a sports car with X horsepower, Toyota would need to counteract with a car rated at X+Y horsepower, while Mazda would need to create an even more powerful sports car, and so on.

In the span of a couple of generations, carmakers would end up spending a massive amount of R&D money to make more powerful cars that consumers can barely use. That would sound particularly useless in a country where the highest top speed is 120 kph (75 mph) and is filled with tight and crowded roads. Oddly enough, a similar 'arms race' ended badly in 1960s USA, which resulted in the death of the original wave of muscle cars.

The 1988 Gentlemen's Agreement profoundly impacted the Japanese automotive landscape. On the one hand, it created a focus on innovation within constraints, leading to advances in engine efficiency, aerodynamics, and vehicle stability.

Most Japanese carmakers found creative ways to enhance performance and driving experience without breaching the agreed-upon limits. Technologies such as sequential turbocharging, variable-valve timing, advanced all-wheel-drive systems, and sophisticated aerodynamics flourished during the era.

On the other hand, the agreement is often credited with sparking a sort of "power war" beneath the surface. Manufacturers tried to get as close to the horsepower ceiling as possible while investing in handling and braking improvements, but many, if not most, of JDM sports cars of the 1990s broke that limit.

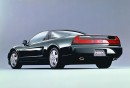

This led to a golden era of Japanese sports cars in the 1990s, including icons like the Nissan Skyline GT-R, Toyota Supra, Honda NSX, Mitsubishi 3000 GT, and Mazda RX-7.

Apart from the NSX, which had a naturally aspirated engine, all these automotive legends are said to have developed more than their advertised outputs. Nobody believed that a 1989 Nissan Skyline GT-R R32 had an identical output to the R34, which came a decade later.

Without the Gentlemen's Agreement, we would likely have never had innovations like Nissan's HICAS or ATTESA systems, which revolutionized the sports car industry, Mitsubishi's active aerodynamics on the 3000GT, or the handling prowess of the Honda/Acura NSX and Mazda RX-7.

The Gentlemen's Agreement began to slowly turn toward its eventual disappearance in the early 2000s, culminating with the introduction of the fourth-generation Honda Legend in 2004. For the first time on a JDM car since 1988, the Legend's 3.5-liter V6 had an advertised output of 296 HP (300 PS), signaling the official end of the agreement.

Several factors probably contributed to the unwritten rule's demise, including advancements in safety technology, better road infrastructure, and consumer demand for more powerful cars.

On top of it, Japanese automakers had started to face increasing pressure to better compete with foreign car brands, which were not subjected to similar restrictions and obviously boasted much higher horsepower figures.

While the Japanese Gentlemen's Agreement on horsepower is no longer in effect, its legacy remains thanks to the awesome sports car it indirectly helped produce. Most Japanese sports cars developed in the 1990s remain highly coveted by enthusiasts today.

Despite the advertised output restriction technically resulting in a level playing field, competition managed to exist, with manufacturers striving to offer the best handling, acceleration, and technological features on a car just shy of the 276 HP ceiling.

That said, while improvements in vehicle safety features, such as advanced airbag systems, electronic stability control, and better road infrastructure, reduced the rationale for maintaining the horsepower cap, the 112 mph speed governors are still in place on JDM cars.

Known as the Japanese Gentlemen's Agreement, it focused on horsepower and top speed limits for domestically sold vehicles. This agreement, which took place during the late 20th century, primarily the 1990s, saw all major Japanese automakers cap their vehicles' maximum horsepower and top speeds to specific thresholds.

Specifically, all Japanese cars sold in the island country between 1988 and 2004 had their advertised powertrain outputs capped at 276 HP (280 PS). There was no government set of rules to enforce this odd agreement, and plenty of sports cars unofficially broke it, but then again, this is the very definition of a 'gentlemen's agreement.'

With that in mind, I decided to explore this intriguing agreement's origins, implications, and eventual dissolution, which coincidentally happened exactly two decades ago.

Origins of the Agreement

By the late 1980s, Japan's bubble economy had led to a surge in high-performance, technologically advanced cars. As speeds increased, so did concerns over road safety and the potential for regulatory backlash.

The Japanese economic miracle that had started after World War II was also hurling toward a sharp end, which probably precipitated the need for a form of self-regulation in some areas of the industry.

In other words, this method of self-restraint, also known as a strong cultural concept called 'jishu-kisei,' was seen by many as a blessing instead of a killjoy. Oddly enough, the 276-horsepower threshold was rooted in a slightly older rule, which was stipulated over a decade earlier by the Japan Automobile Manufacturers Association (JAMA).

In the mid to late '70s, road fatalities in the Land of the Rising Sun had started to increase exponentially, and many saw this as a result of a growing number of sports cars that were getting faster and faster.

That is when a nationwide ban on cars that can go faster than 112 mph (180 kph) was implemented, regulated by a speed governor installed from the factory in every JDM vehicle built since then.

The '276-horsepower' limit on advertised output came on top of the speed limit rule in 1988, but it was more of a handshake than a signed contract.

Official and Unofficial Reasons

Others believed that the output limit was introduced simply to avoid a power race that would eventually be negative for both carmakers and consumers.

For example, without the limit, if Nissan introduced a sports car with X horsepower, Toyota would need to counteract with a car rated at X+Y horsepower, while Mazda would need to create an even more powerful sports car, and so on.

In the span of a couple of generations, carmakers would end up spending a massive amount of R&D money to make more powerful cars that consumers can barely use. That would sound particularly useless in a country where the highest top speed is 120 kph (75 mph) and is filled with tight and crowded roads. Oddly enough, a similar 'arms race' ended badly in 1960s USA, which resulted in the death of the original wave of muscle cars.

Impacts on the Japanese Automotive Industry

Most Japanese carmakers found creative ways to enhance performance and driving experience without breaching the agreed-upon limits. Technologies such as sequential turbocharging, variable-valve timing, advanced all-wheel-drive systems, and sophisticated aerodynamics flourished during the era.

On the other hand, the agreement is often credited with sparking a sort of "power war" beneath the surface. Manufacturers tried to get as close to the horsepower ceiling as possible while investing in handling and braking improvements, but many, if not most, of JDM sports cars of the 1990s broke that limit.

This led to a golden era of Japanese sports cars in the 1990s, including icons like the Nissan Skyline GT-R, Toyota Supra, Honda NSX, Mitsubishi 3000 GT, and Mazda RX-7.

Apart from the NSX, which had a naturally aspirated engine, all these automotive legends are said to have developed more than their advertised outputs. Nobody believed that a 1989 Nissan Skyline GT-R R32 had an identical output to the R34, which came a decade later.

Without the Gentlemen's Agreement, we would likely have never had innovations like Nissan's HICAS or ATTESA systems, which revolutionized the sports car industry, Mitsubishi's active aerodynamics on the 3000GT, or the handling prowess of the Honda/Acura NSX and Mazda RX-7.

The End of the Agreement and its Legacy

Several factors probably contributed to the unwritten rule's demise, including advancements in safety technology, better road infrastructure, and consumer demand for more powerful cars.

On top of it, Japanese automakers had started to face increasing pressure to better compete with foreign car brands, which were not subjected to similar restrictions and obviously boasted much higher horsepower figures.

While the Japanese Gentlemen's Agreement on horsepower is no longer in effect, its legacy remains thanks to the awesome sports car it indirectly helped produce. Most Japanese sports cars developed in the 1990s remain highly coveted by enthusiasts today.

Despite the advertised output restriction technically resulting in a level playing field, competition managed to exist, with manufacturers striving to offer the best handling, acceleration, and technological features on a car just shy of the 276 HP ceiling.

That said, while improvements in vehicle safety features, such as advanced airbag systems, electronic stability control, and better road infrastructure, reduced the rationale for maintaining the horsepower cap, the 112 mph speed governors are still in place on JDM cars.