Bigger is better in the U.S. Military. Be it artillery pieces, missiles, machine guns, and, yes, airplanes. But what happens when an aircraft is so huge, so ungodly massive, and certifiably chunky that even U.S. Army Air Forces struggled to figure out what to do with it? Believe it or not, such a situation really did unfold. It didn't have anything to do with the Boeing B-29 Superfortress either, but rather an entirely different airframe that's all but forgotten nowadays. This is the story of the Douglas XB-19, an experimental mega-bomber you've probably never heard of.

Even in the late 1930s, in the days immediately before the United States formally entered the Second World War, the Army Air Corps, the precursor to the modern-day USAF, could see the writing on the wall. Sooner rather than later, the United States was going to be at war, and they'd be damned if foreign aggressors perceived the American armed forces as being incapable of innovation on the scale of Germany or Japan. What the Army Air Corps required was an aerial weapon, the likes of which were nearly unheard of in Axis-aligned air forces.

One such weapon was large strategic bombers. Enormous warpanes capable of taking off from Allied airspace in Europe or Asia, dropping massive amounts of high-explosive ordinance, potentially fighting their way out of danger if need be, and carrying enough fuel to fly back home again. This is in stark contrast to Axis bombers of the war, often consisting of swarms of smaller, twin-engine bombers instead of quad-engine leviathans. In the span of a single decade, American heavy bombers had evolved from rickety biplanes with open cockpits to sleek, imposing beasts of machines sprawling with defensive machine guns and internal weapons bays big enough to carry several tons of bombs, making radical designs once unthinkable suddenly within the realm of possibility. Indeed, it was the Army Air Corps' wish to learn more about the flight characteristics of "giant bombers" beginning in the mid-1930s that spurred the C.

One American aerospace contractor who answered the call to fulfill the Army Air Corps' request for a giant bomber was the Douglas Aircraft Company of Southern California in 1935. By this time, Douglas was gearing up to introduce the iconic DC-3 twin-engine airliner and its military cousin, the C-47 Skytrain, into service. Becoming one of the most successful single aircraft lineages in the history of flight in the process. This newly-tapped revenue stream would come in handy for designing more ambitious and specialized aircraft, such as what the USAAC desired with a giant strategic bomber.

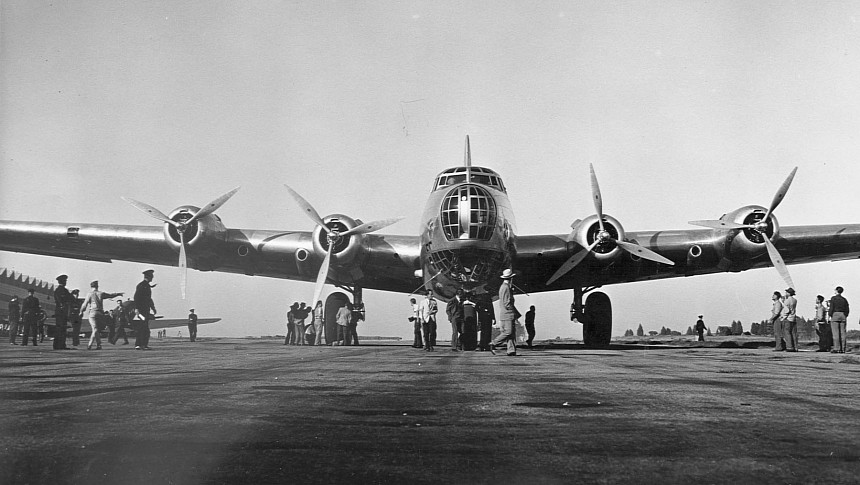

Other key innovations like a tricycle-style landing gear, onboard AC electrical power, and power-actuated control surfaces also ran across Douglas' desk during this period. These were traits and qualities that directly led to the blueprints for what was first christened the XBLR-2 and later the Douglas XB-19. With dimensions of just over 132 feet (40.3 m) long and a staggering 212-foot (64.6-m) wingspan, the prototype XB-19 was almost double the width of operational American strategic bombers like the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress or the Consolidated B-24 Liberator. A maximum takeoff weight of over 160,000 lbs (72,574.7 kg) on the part of the XB-19 was nothing to sneeze at either. That's over three times the maximum takeoff weight of a B-17.

At the heart of the Douglas XB-19 was an engine just as new on the scene as the bomber itself was, four Wright R-3350 Duplex Cyclone 18-cylinder radials. Though most famous for its use on the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, the R-3350 originally cut its teeth on the XB-19, at least at first. With 2,000 horsepower per engine to work with, this was only enough for the XB-19 to cruise at around 125 mph (217 km/h, 117 kn) and top out at just over 220 mph (354 kph). Perhaps impressive for a massive bomber, but still mince meat for even a gingerly flown single-engine fighter of the day. But what the XB-19 lacked in speed or any semblance of agility, it more than made up for in range and firepower.

On just its main fuel tank alone, the XB-19 could fly for up to 5,200 mi (8,400 km, 4,500 nmi) at a time. With its auxiliary wing tanks filled, this range extended to a scarcely believable 7,710 mi (12,410 km, 6,700 nmi). Easily enough to take off from air bases in England or the Pacific Islands, fly to target cities in German or Japanese-occupied territory, unleash a torrent of up to 18,700 lb (8,500 kg) of ordnance from its internal bomb bay, and then fly its way home again with fuel to spare. If things ever got out of hand, a defensive array of five M2 Browning 50 caliber machine guns, M1919 30 caliber machine guns, and two 37mm autocannons could have made mince meat out of lightly armored interceptors.

It all looked tempting, at least on paper, and the sheer spectacle of such a massive airplane in the early 1940s attracted considerable fanfare wherever the XB-19 flew. But the truth of the matter was far, far different. Because no sooner did the XB-19 make its first flight in June 1941 was the platform already pretty much totally obsolete. Douglas had intended to have the XB-19 in the air far sooner. But consistent delays in manufacturing and development of the airframe combined with reliability problems with the new R-3350 engines to the point where even Douglas themselves wanted to cancel the program.

But, like a spoiled, petulant child who doesn't want to eat vegetables, the Army Air Corps compelled Douglas to finish the program. This resulted in the XB-19's radial engines being swapped for the experimental Allison V-3420-11 W24 engines, most famous for their use in the catastrophic Fisher P-75 Eagle program in 1943. Of course, this was most likely because Boeing needed a few extra R-3350 engines for their own far more successful B-29 Superfortress production. Of course, bigger and better bomber prototypes like the Northrop YB-35 flying wing and the truly colossal YB-36 Peacemaker were already under development by this stage. Meaning that the XB-19s days were well and truly numbered even well before the end of the war.

With its flight testing complete by the end of World War II, a half-baked attempt was made at making the XB-19 a cargo aircraft. But, with more efficient and powerful turboprop transport planes on the horizon, these modifications were never completed. The sole XB-19 manufactured made its final flight on August 17th, 1946, before being transported to the Davis-Monthan Army Air Base in Tucson, Arizona, for long-term storage later that year. By the time the plane was retired, it'd served as a proof of concept for even larger strategic bombers going forward, like the B-36, while also testing vital flight components for Douglas' real post-war money maker, the DC-4 quad-engine airliner.

With this in mind, it'd be wrong to call the XB-19 program a complete failure. Even if it itself didn't spawn a lineage of its own strategic bombers, the lessons learned from the program paid dividends in the end. The XB-19 sat collecting dust in storage for three long years before it was finally scrapped in 1949. By this point, the first XB-36 Peacemaker had already made its maiden flight the year before. An attempt was made to preserve the XB-19 before its ultimate fate. But because the National Museum of the United States Air Force was still in its infancy at that time, these attempts failed.

Today, only a handful of artifacts from the great plane still exist, including two of its colossal main tires. One of which currently resides at the Hill Aerospace Museum next to Hill Air Force Base in Ogden, Utah, while the other is in the collection of the above-mentioned National Museum of the U.S. Air Force near Dayton, Ohio. Thanks to this preservation, it's at least possible to appreciate the scale of Douglas' achievement. To have manufactured an aircraft of that size in the late 30s and early 40s is nothing short of remarkable.

One such weapon was large strategic bombers. Enormous warpanes capable of taking off from Allied airspace in Europe or Asia, dropping massive amounts of high-explosive ordinance, potentially fighting their way out of danger if need be, and carrying enough fuel to fly back home again. This is in stark contrast to Axis bombers of the war, often consisting of swarms of smaller, twin-engine bombers instead of quad-engine leviathans. In the span of a single decade, American heavy bombers had evolved from rickety biplanes with open cockpits to sleek, imposing beasts of machines sprawling with defensive machine guns and internal weapons bays big enough to carry several tons of bombs, making radical designs once unthinkable suddenly within the realm of possibility. Indeed, it was the Army Air Corps' wish to learn more about the flight characteristics of "giant bombers" beginning in the mid-1930s that spurred the C.

One American aerospace contractor who answered the call to fulfill the Army Air Corps' request for a giant bomber was the Douglas Aircraft Company of Southern California in 1935. By this time, Douglas was gearing up to introduce the iconic DC-3 twin-engine airliner and its military cousin, the C-47 Skytrain, into service. Becoming one of the most successful single aircraft lineages in the history of flight in the process. This newly-tapped revenue stream would come in handy for designing more ambitious and specialized aircraft, such as what the USAAC desired with a giant strategic bomber.

Other key innovations like a tricycle-style landing gear, onboard AC electrical power, and power-actuated control surfaces also ran across Douglas' desk during this period. These were traits and qualities that directly led to the blueprints for what was first christened the XBLR-2 and later the Douglas XB-19. With dimensions of just over 132 feet (40.3 m) long and a staggering 212-foot (64.6-m) wingspan, the prototype XB-19 was almost double the width of operational American strategic bombers like the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress or the Consolidated B-24 Liberator. A maximum takeoff weight of over 160,000 lbs (72,574.7 kg) on the part of the XB-19 was nothing to sneeze at either. That's over three times the maximum takeoff weight of a B-17.

On just its main fuel tank alone, the XB-19 could fly for up to 5,200 mi (8,400 km, 4,500 nmi) at a time. With its auxiliary wing tanks filled, this range extended to a scarcely believable 7,710 mi (12,410 km, 6,700 nmi). Easily enough to take off from air bases in England or the Pacific Islands, fly to target cities in German or Japanese-occupied territory, unleash a torrent of up to 18,700 lb (8,500 kg) of ordnance from its internal bomb bay, and then fly its way home again with fuel to spare. If things ever got out of hand, a defensive array of five M2 Browning 50 caliber machine guns, M1919 30 caliber machine guns, and two 37mm autocannons could have made mince meat out of lightly armored interceptors.

It all looked tempting, at least on paper, and the sheer spectacle of such a massive airplane in the early 1940s attracted considerable fanfare wherever the XB-19 flew. But the truth of the matter was far, far different. Because no sooner did the XB-19 make its first flight in June 1941 was the platform already pretty much totally obsolete. Douglas had intended to have the XB-19 in the air far sooner. But consistent delays in manufacturing and development of the airframe combined with reliability problems with the new R-3350 engines to the point where even Douglas themselves wanted to cancel the program.

But, like a spoiled, petulant child who doesn't want to eat vegetables, the Army Air Corps compelled Douglas to finish the program. This resulted in the XB-19's radial engines being swapped for the experimental Allison V-3420-11 W24 engines, most famous for their use in the catastrophic Fisher P-75 Eagle program in 1943. Of course, this was most likely because Boeing needed a few extra R-3350 engines for their own far more successful B-29 Superfortress production. Of course, bigger and better bomber prototypes like the Northrop YB-35 flying wing and the truly colossal YB-36 Peacemaker were already under development by this stage. Meaning that the XB-19s days were well and truly numbered even well before the end of the war.

With this in mind, it'd be wrong to call the XB-19 program a complete failure. Even if it itself didn't spawn a lineage of its own strategic bombers, the lessons learned from the program paid dividends in the end. The XB-19 sat collecting dust in storage for three long years before it was finally scrapped in 1949. By this point, the first XB-36 Peacemaker had already made its maiden flight the year before. An attempt was made to preserve the XB-19 before its ultimate fate. But because the National Museum of the United States Air Force was still in its infancy at that time, these attempts failed.

Today, only a handful of artifacts from the great plane still exist, including two of its colossal main tires. One of which currently resides at the Hill Aerospace Museum next to Hill Air Force Base in Ogden, Utah, while the other is in the collection of the above-mentioned National Museum of the U.S. Air Force near Dayton, Ohio. Thanks to this preservation, it's at least possible to appreciate the scale of Douglas' achievement. To have manufactured an aircraft of that size in the late 30s and early 40s is nothing short of remarkable.