Several cultures tell a story of a little bird that tried to put out a fire carrying water in its even tinier beak. When asked what it was trying to do, the bird said it was doing its part. That represents taking action, which is how people should also look at clean cars. When Transport & Environment (T&E) said plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) are no climate solution, it was correct for the same reason the little bird would not manage to kill the blaze: no passenger car will ever save the environment, regardless of what powers it.

Even if all vehicles were electric, climate change would still happen because fossil fuels are necessary for many other activities. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), transportation is responsible for only 14% of man-made GHG (greenhouse gases). Passenger cars are just a fraction of transportation emissions, reducing the impact a fleet of electric passenger cars could have even more. I wish IPCC had broken down all transportation elements and how they contribute to carbon emissions, but it didn’t.

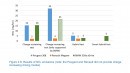

Anyway, the panel helped to demonstrate why entities like T&E must consider the whole scenario before deciding what a climate solution is and what it is not. Most carbon emissions come from electricity and heat production (25%), followed by AFOLU (Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Land Use), with 24%, and industrial activity (21%). That’s 70% of all fossil fuel use. Compare that to the less than 14% of emissions passenger cars generate, and you’ll stop believing cars are the evil guys in climate change. They’re not.

That said, no personal transportation solution will move the needle as much as people think they will when it comes to worsening the greenhouse effect – a necessary phenomenon to keep the planet warm. Most efforts to reduce oil demand have to go to other economic sectors. The focus on electric vehicles should be for different reasons, equally important, such as the health of big cities’ populations and preventing severe-use conditions that make emissions higher and damage crucial car components.

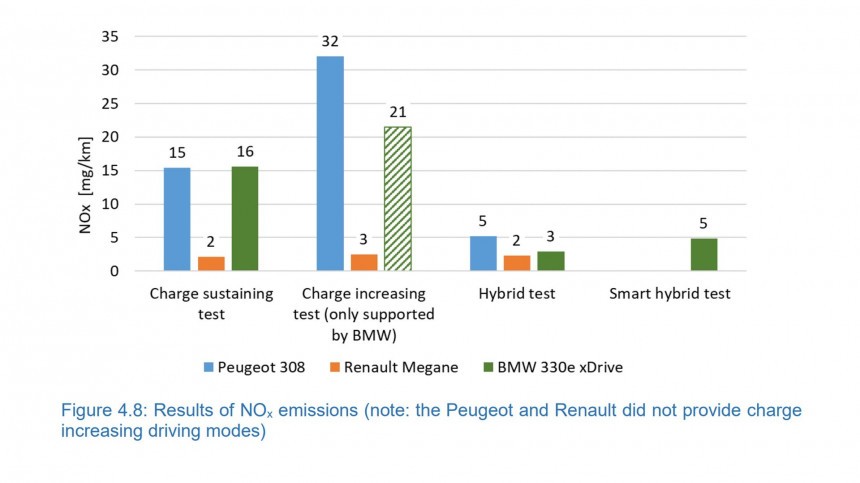

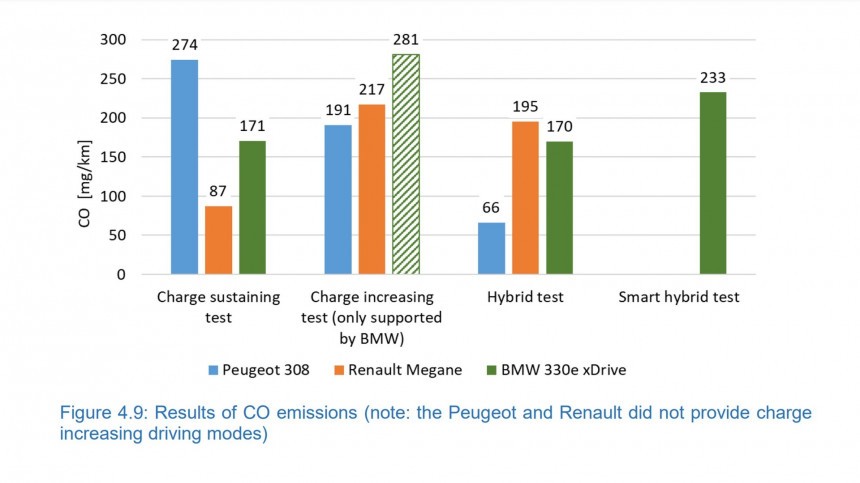

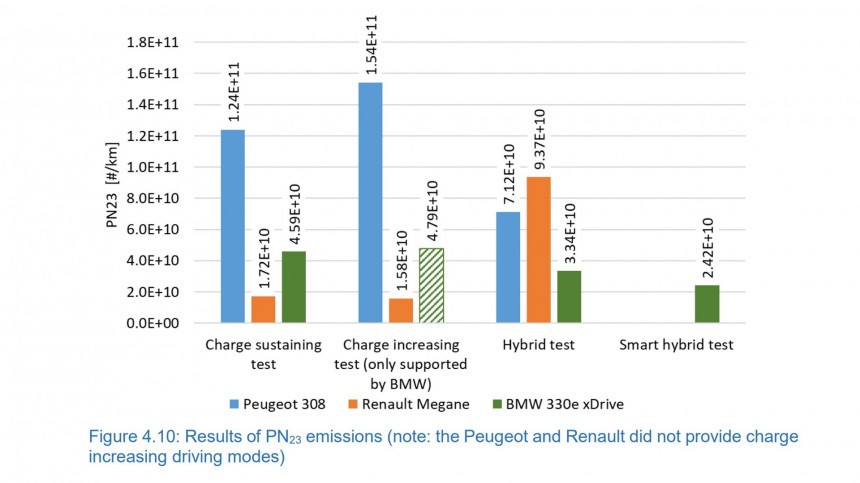

Having thousands or even millions of vehicles in a relatively small area is what creates smog and respiratory diseases. Nitrogen oxides, ozone, particulates, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, and benzene are hazardous to human health. When emitted on highways in rural areas, they tend to dissipate, but that does not happen in traffic jams in ample avenues inside cities. This is where BEVs, FCEVs, and even PHEVs can shine, regardless of what T&E has to say about them.

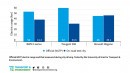

Severe use happens when you only travel short distances with your combustion-engined vehicle. That prevents the engine from reaching its ideal working temperature, directly affecting the lubrication of all mobile parts inside the mill. While the engine heats up, it emits more pollutants because the catalytic converter needs to be at the right (high) temperature to start acting. Most machines and transmissions are conceived to work at higher speeds and on roads – that’s their ideal environment. They even have an optimal rotational speed, which they cannot keep for long periods when the engine is used to power the wheels.

Battery-electric cars do not have that problem because their motors can work just fine without the need to heat up. Their severe-use conditions are pretty different from those combustion-engined vehicles face. They are related to constantly fast charging the battery pack, which can happen for people who do not have the conditions to charge their EVs at home or those traveling farther than a full charge allows.

Curiously, a PHEV can avoid both severe use conditions if it is used correctly. Drivers must use them in electric mode in the city, avoiding pollution emissions in traffic, and do not have to fast charge the battery on long trips. It could be the best of both worlds if adequately used.

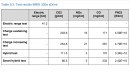

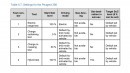

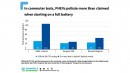

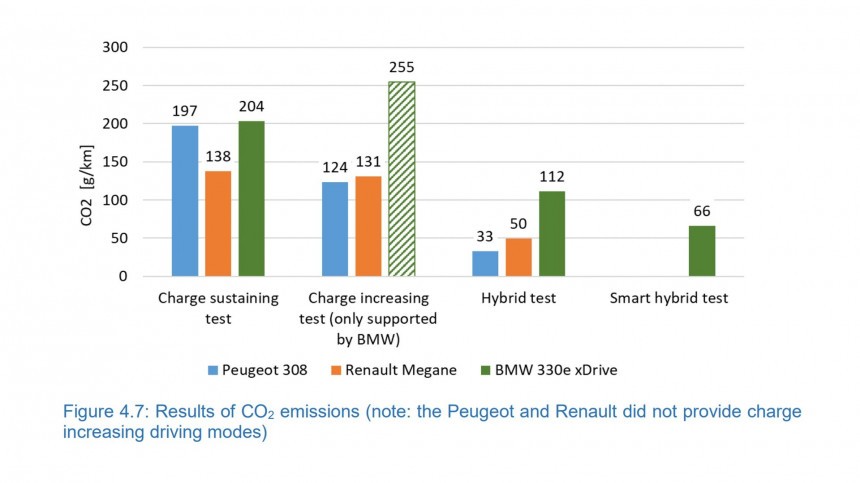

T&E’s main argument against PHEVs is that they pollute way more than claimed. To prove that, it asked the Technical University of Graz (TU Graz) to test three plug-in hybrids that were not SUVs. The BMW 330e xDrive Touring was the only one to go through all tests, and it was also the vehicle with the highest carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. T&E said its official number is 36 g/km of CO2, but that the number obtained in the tests was 112 g/km, 3.4 times the official figure.

The vehicles were simply driven and had their emissions measured. However, the tests did not follow any protocol. When I checked BMW’s information about that, the German carmaker had this statement in its technical data PDF:

“Fuel consumption, CO2 emission figures, power consumption, and range were measured using the methods required according to Regulation VO (EC) 2007 /7 15 as amended. They refer to vehicles on (sic) the automotive market in Germany. (...) All figures are already calculated on the basis of the new WLTP test cycle.”

Testing protocols exist to allow comparisons, which are not possible when tests are made under different conditions and procedures. This is the reason BMW has obtained numbers that are not even close to those TU Graz measured. On top of that, there are so many variables involving PHEVs (especially driving modes) that there is little chance that the results are repeatable without some rules to follow. If the Austrian university followed the same protocol, it would be a scandal if they were not the same or at least pretty similar to those the German carmaker released. But there is more.

T&E said the official CO2 emission number for the 330e was 36 g/km. BMW actually discloses it goes from 35 g/km to up to 48 g/km. That has to do with the fuel consumption its tests presented: from 1.5 l/100 km to 2.1 l/100 km, which translates to 66.7 km/l (156.8 mpg) and 47.6 km/l (112 mpg). Knowing that each liter of gasoline generates around 2.3 kilograms (2,300 g) of carbon dioxide, you can calculate the official numbers disclosed by the German carmaker. It is not clear where T&E read the 330e emitted 36 g/km.

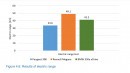

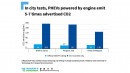

When 112 g/km are compared to 36 g/km, they seem really high. That would be even higher compared to the 35 g/km that BMW also informs. However, when the comparison basis is 48 g/km, that’s 2.3 times higher than this official figure. It still makes the station wagon look kind of dirty, but that’s less than 3.4 times. Now compare the PHEV to the 330 xDrive Touring – the ICE version of the station wagon TU Graz tested – and the plug-in hybrid station wagon will seem pretty clean.

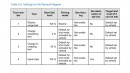

According to the German carmaker, the 330 xDrive Touring has a fuel consumption that ranges from 7.3 l/100 km (32.2 mpg) to up to 8.1 l/100 km (29 mpg). In other words, the vehicle with no electric assistance emits between 164 g/km and 182 g/km. Using BMW’s numbers, obtained under the same test protocols, the 330e is up to 4.7 times cleaner than the 330. Isn’t that a victory for anyone fighting for fewer carbon emissions, less pollution, and more efficient cars?

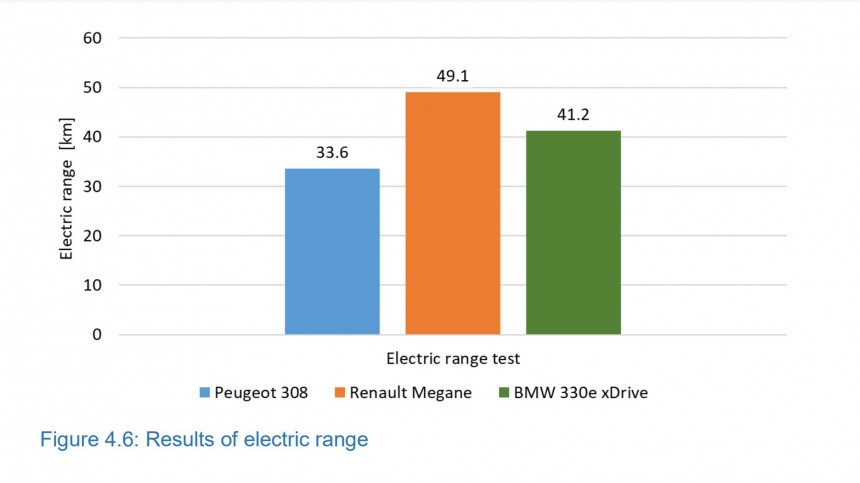

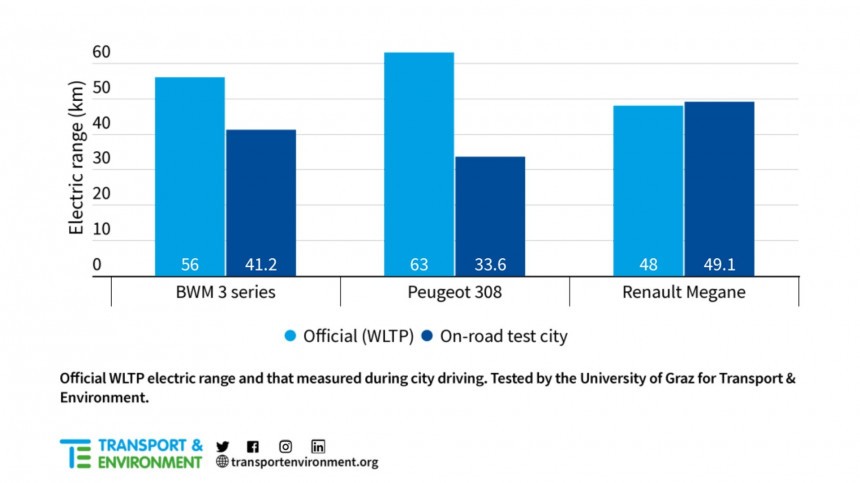

On top of that, the 330e can run exclusively in EV mode, which is what makes it attractive in the city without the need to carry a massive battery pack. T&E said it could run only 41.2 kilometers (25.6 miles) compared to the 56 km (34.8 mi) BMW allegedly states it can run. Again, I could not find the organization’s source. The latest information on the 330e xDrive Touring states it runs 53 km (32.9 mi) to 61 km (37.9 mi) with a full charge, and the company’s German website currently reduces it even further: 47 km (29.2 mi) to 58 km (36 mi). Although it still does not meet the disclosed EV range in TU Graz’s tests, 41.2 km is closer to 47 km than it is to 56 km.

T&E criticized BMW’s geo-fencing capability as something that made the PHEV emit more outside cities, increasing its emissions. Considering the 330e xDrive can use the combustion engine to charge its battery pack, that’s expected and can be a plus for people who do not want to use fossil fuels in populated areas. However, the organization also said that the geo-fencing tech did not prevent the combustion engine from firing up twice in the city. That is a more than pertinent criticism if the battery pack still had the juice to feed the electric motor. While it does, the combustion engine should not kick off.

In the end, T&E wants governments to refrain from giving incentives to PHEVs. They should be exclusive to battery-electric cars because plug-in hybrids would have “artificially low CO2” emissions. To prevent that, the organization defends that these vehicles should match some requirements to be eligible, such as a minimum electric range of 80 km (49.7 mi), fast charging capability, a combustion engine that emits a maximum of 139 g/km, and an electric motor as powerful as their ICEs.

These are excellent requirements for PHEVs anywhere in the world. Anyway, discarding the current ones as mere greenwashing is an error. They are still enough for people that drive short distances. If properly charged and operated, they may prevent the emission of hazardous pollutants where it matters the most: inside cities. Their battery packs are also small, which means they may not cost a fortune to replace when they fail after the warranty is over. That’s not something you can say about BEVs, as a recent story I wrote shows quite well.

If the main goal is to prevent carbon emissions in a meaningful way, T&E is focusing on the wrong target. If the idea is to make cities and their populations healthier, anything that prevents an engine from running in an urban environment should be welcome. Larger battery packs with range extenders would be the sweet spot, but bashing current solutions and stimulating a single one does not sound wise. PHEVs are not "a dangerous distraction," and BEVs are not entirely good. Above all, none of these vehicles will ever save the planet. They may save personal transportation, which is enough for us to celebrate.

Anyway, the panel helped to demonstrate why entities like T&E must consider the whole scenario before deciding what a climate solution is and what it is not. Most carbon emissions come from electricity and heat production (25%), followed by AFOLU (Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Land Use), with 24%, and industrial activity (21%). That’s 70% of all fossil fuel use. Compare that to the less than 14% of emissions passenger cars generate, and you’ll stop believing cars are the evil guys in climate change. They’re not.

Having thousands or even millions of vehicles in a relatively small area is what creates smog and respiratory diseases. Nitrogen oxides, ozone, particulates, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, and benzene are hazardous to human health. When emitted on highways in rural areas, they tend to dissipate, but that does not happen in traffic jams in ample avenues inside cities. This is where BEVs, FCEVs, and even PHEVs can shine, regardless of what T&E has to say about them.

Battery-electric cars do not have that problem because their motors can work just fine without the need to heat up. Their severe-use conditions are pretty different from those combustion-engined vehicles face. They are related to constantly fast charging the battery pack, which can happen for people who do not have the conditions to charge their EVs at home or those traveling farther than a full charge allows.

T&E’s main argument against PHEVs is that they pollute way more than claimed. To prove that, it asked the Technical University of Graz (TU Graz) to test three plug-in hybrids that were not SUVs. The BMW 330e xDrive Touring was the only one to go through all tests, and it was also the vehicle with the highest carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. T&E said its official number is 36 g/km of CO2, but that the number obtained in the tests was 112 g/km, 3.4 times the official figure.

“Fuel consumption, CO2 emission figures, power consumption, and range were measured using the methods required according to Regulation VO (EC) 2007 /7 15 as amended. They refer to vehicles on (sic) the automotive market in Germany. (...) All figures are already calculated on the basis of the new WLTP test cycle.”

T&E said the official CO2 emission number for the 330e was 36 g/km. BMW actually discloses it goes from 35 g/km to up to 48 g/km. That has to do with the fuel consumption its tests presented: from 1.5 l/100 km to 2.1 l/100 km, which translates to 66.7 km/l (156.8 mpg) and 47.6 km/l (112 mpg). Knowing that each liter of gasoline generates around 2.3 kilograms (2,300 g) of carbon dioxide, you can calculate the official numbers disclosed by the German carmaker. It is not clear where T&E read the 330e emitted 36 g/km.

According to the German carmaker, the 330 xDrive Touring has a fuel consumption that ranges from 7.3 l/100 km (32.2 mpg) to up to 8.1 l/100 km (29 mpg). In other words, the vehicle with no electric assistance emits between 164 g/km and 182 g/km. Using BMW’s numbers, obtained under the same test protocols, the 330e is up to 4.7 times cleaner than the 330. Isn’t that a victory for anyone fighting for fewer carbon emissions, less pollution, and more efficient cars?

T&E criticized BMW’s geo-fencing capability as something that made the PHEV emit more outside cities, increasing its emissions. Considering the 330e xDrive can use the combustion engine to charge its battery pack, that’s expected and can be a plus for people who do not want to use fossil fuels in populated areas. However, the organization also said that the geo-fencing tech did not prevent the combustion engine from firing up twice in the city. That is a more than pertinent criticism if the battery pack still had the juice to feed the electric motor. While it does, the combustion engine should not kick off.

These are excellent requirements for PHEVs anywhere in the world. Anyway, discarding the current ones as mere greenwashing is an error. They are still enough for people that drive short distances. If properly charged and operated, they may prevent the emission of hazardous pollutants where it matters the most: inside cities. Their battery packs are also small, which means they may not cost a fortune to replace when they fail after the warranty is over. That’s not something you can say about BEVs, as a recent story I wrote shows quite well.

If the main goal is to prevent carbon emissions in a meaningful way, T&E is focusing on the wrong target. If the idea is to make cities and their populations healthier, anything that prevents an engine from running in an urban environment should be welcome. Larger battery packs with range extenders would be the sweet spot, but bashing current solutions and stimulating a single one does not sound wise. PHEVs are not "a dangerous distraction," and BEVs are not entirely good. Above all, none of these vehicles will ever save the planet. They may save personal transportation, which is enough for us to celebrate.