For most car owners, choosing an electric car is not viable because of short ranges and long charging times. That means the race for much better batteries is already on. But in the meantime, the industry is testing alternatives to ease the pressure on battery research. The question is how feasible are they.

Statistics show that the average American drives around 40 miles (56 km) per day. That’s less than the shortest-range electric vehicle in the worst-case condition. But statistics don’t consider those scenarios when the average American simply wants to go on a hundred- or thousand-mile trip in his car.

They also don’t apply to long-haul freight, especially when perishable goods need to be on time to their destination. Today’s electric vehicles simply can’t match the long range offered by internal combustion engines and the fast way we “charge” the tank at a gas station.

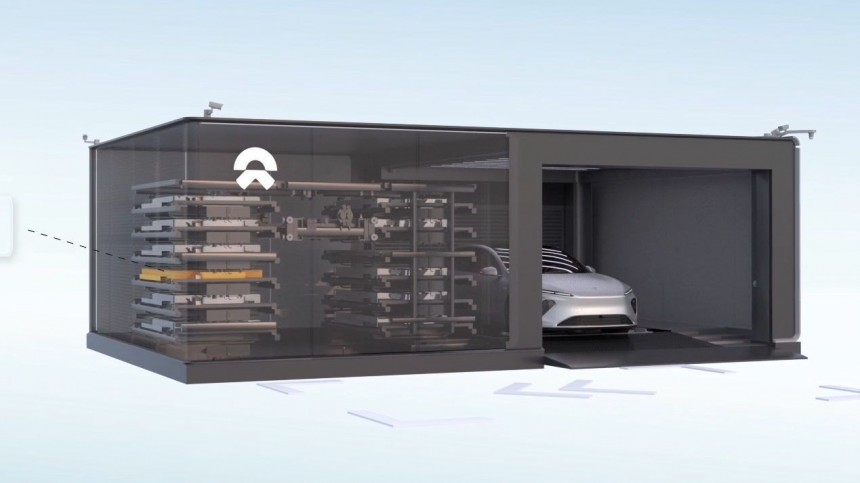

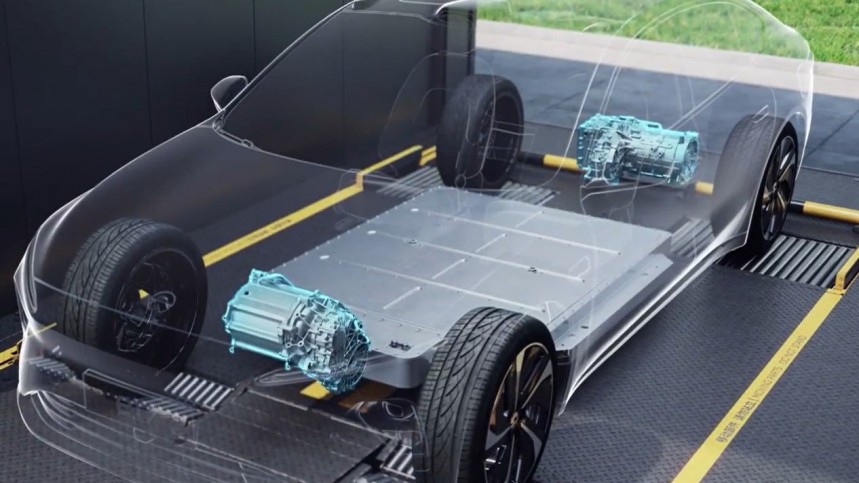

In the case of NIO, it allegedly takes around 3 minutes for the fully automatic system to swap a depleted battery with a fully charged one, good for other hundreds of miles of driving. In the case of Gogoro, the much smaller battery is simply swapped by the rider, and in Taiwan’s capital Taipei, there’s a swap station every kilometer – less than 0.6 miles.

So why hasn't everyone jumped into swap battery already? Well, there’s some history with this technology that doesn’t make it the first choice for everybody. As unbelievable as it may seem, swap battery technology is old. Very old. The first concept appeared in the late 1890s, while the first real-world operating service was put in place in Connecticut.

Between 1910 and 1924, the General Vehicle Company offered a subscription-based battery-swapping service for the customers of its GeVeCo electric trucks. Almost a century later, the U.S.-Israeli start-up Better Place came up with the idea of a battery-swapping station infrastructure, and the first one was opened in 2008, in Tel Aviv.

Soon after, Better Place partnered with Renault-Nissan, and in 2012 they launched Renault Fluence Z.E. in Israel and Denmark. It was the first mass-market battery-swapping electric car, but unfortunately, the business model soon proved not to be economically feasible.

Secondly, the business scenario required the car industry to quickly adopt the swap battery technology, but there were hardly a few carmakers into electromobility at that time. Thirdly, Fluence’s battery cost was around $30,000 (€23,300 in 2012), and stockpiling many of them was too costly.

Finally, although the battery leasing program made Renault and Nissan EVs a little more affordable, the large public wasn’t enthusiastic about it. This is odd because the vast majority of new car customers in the western world prefer paying installments for their new car.

Tesla was interested in swapping battery technology for a while, but in 2015 they gave up on the idea, because “battery swapping is riddled with problems and not suitable for widescale use.” It seems that most problems were caused by worn connecting electronics and the body’s rigidity issues. BMW also showed reluctance by calling this idea “a waste of time.”

Besides, this technology requires standardization, which is very hard to put in place because of the very different types of cars and batteries’ chemistries and capacities and many other technical details. Many fear that such a system would lead to a monopoly in the market because of patent-protected technologies.

Then the government started pouring billions into research for this technology and it sparked a flock of pilot projects. At the end of 2021, China was the first to release industry standards for battery swapping technology.

And now, several Chinese corporations plan to establish a network of 25,000 swapping battery stations in China by 2025. It’s a one-hundred-fold increase than today, in just two years!

But for the moment, no western carmaker is willing to follow in NIO’s footsteps, mainly because of the huge costs and technical issues. Many analysts estimate that plug-in fast-charging station networks are faster, easier, and cheaper to put in place. Especially thanks to government subsidies.

The charging time factor will gradually be solved by rapid advancement in battery tech, so too few investors are willing to bet on swapping battery tech. The U.S. or EU’s subsidy programs don’t cover this field, and many consider a global industry standardization not likely because of economic and political tensions between the U.S. and China.

So, while battery-swapping technology looks easy and convenient for the end user, the background hurdles seem much more serious for western companies and policymakers. However, we should not dismiss this idea just yet, because it could be pretty interesting for the oil companies.

For instance, state-owned Chinese oil company Sinopec is deeply involved in developing swapping battery station networks, along with Aulton, NIO and Geely. It fits conveniently the business-as-usual model of gas station networks, and it keeps users “addicted” to their services.

In 2022, Shell, Repsol and Eneos invested more than $200 million (€189 million) in the San Francisco-based startup Ample, which currently runs pilot programs with Uber. The start-up aims to develop the battery swap tech especially for fleets, where vehicles are heavily utilized and short charging time is of the essence.

We’ll keep an eye on how things will evolve in the following years. In the next part of this material, we’ll take a look at the conductive charging alternative – maybe this is the real deal for getting electric vehicles on par with their ICE counterparts and making “range anxiety” history.

They also don’t apply to long-haul freight, especially when perishable goods need to be on time to their destination. Today’s electric vehicles simply can’t match the long range offered by internal combustion engines and the fast way we “charge” the tank at a gas station.

Swapping battery is the fastest way to “charge” an EV

Chinese carmaker NIO and Taiwanese scooter manufacturer Gogoro are today’s leaders in swapping battery technologies. NIO has already deployed 1,300 stations in China, and this year it aims to add another 1,000 stations in China and Europe. Meanwhile, Gogoro has reached almost 350 million battery swaps since it began operations in 2015.In the case of NIO, it allegedly takes around 3 minutes for the fully automatic system to swap a depleted battery with a fully charged one, good for other hundreds of miles of driving. In the case of Gogoro, the much smaller battery is simply swapped by the rider, and in Taiwan’s capital Taipei, there’s a swap station every kilometer – less than 0.6 miles.

Between 1910 and 1924, the General Vehicle Company offered a subscription-based battery-swapping service for the customers of its GeVeCo electric trucks. Almost a century later, the U.S.-Israeli start-up Better Place came up with the idea of a battery-swapping station infrastructure, and the first one was opened in 2008, in Tel Aviv.

Soon after, Better Place partnered with Renault-Nissan, and in 2012 they launched Renault Fluence Z.E. in Israel and Denmark. It was the first mass-market battery-swapping electric car, but unfortunately, the business model soon proved not to be economically feasible.

The drawbacks of swapping batteries

In 2013, Better Place went bankrupt because of several reasons. Firstly, a swap station cost was estimated at $500,000 (€390,000 in 2012). It was almost half the cost of an average petrol station, but it meant a huge investment upfront for putting up a large infrastructure in a reasonably short time.Secondly, the business scenario required the car industry to quickly adopt the swap battery technology, but there were hardly a few carmakers into electromobility at that time. Thirdly, Fluence’s battery cost was around $30,000 (€23,300 in 2012), and stockpiling many of them was too costly.

Finally, although the battery leasing program made Renault and Nissan EVs a little more affordable, the large public wasn’t enthusiastic about it. This is odd because the vast majority of new car customers in the western world prefer paying installments for their new car.

Besides, this technology requires standardization, which is very hard to put in place because of the very different types of cars and batteries’ chemistries and capacities and many other technical details. Many fear that such a system would lead to a monopoly in the market because of patent-protected technologies.

A whole debate around swap-battery tech feasibility

The battery-swapping solution seems more appropriate for heavy-duty vehicles, like trucks or buses. For instance, at the 2008 Summer Olympics, the Beijing Institute of Technology converted 50 electric buses to allow battery swapping.Then the government started pouring billions into research for this technology and it sparked a flock of pilot projects. At the end of 2021, China was the first to release industry standards for battery swapping technology.

And now, several Chinese corporations plan to establish a network of 25,000 swapping battery stations in China by 2025. It’s a one-hundred-fold increase than today, in just two years!

But for the moment, no western carmaker is willing to follow in NIO’s footsteps, mainly because of the huge costs and technical issues. Many analysts estimate that plug-in fast-charging station networks are faster, easier, and cheaper to put in place. Especially thanks to government subsidies.

The charging time factor will gradually be solved by rapid advancement in battery tech, so too few investors are willing to bet on swapping battery tech. The U.S. or EU’s subsidy programs don’t cover this field, and many consider a global industry standardization not likely because of economic and political tensions between the U.S. and China.

So, while battery-swapping technology looks easy and convenient for the end user, the background hurdles seem much more serious for western companies and policymakers. However, we should not dismiss this idea just yet, because it could be pretty interesting for the oil companies.

For instance, state-owned Chinese oil company Sinopec is deeply involved in developing swapping battery station networks, along with Aulton, NIO and Geely. It fits conveniently the business-as-usual model of gas station networks, and it keeps users “addicted” to their services.

In 2022, Shell, Repsol and Eneos invested more than $200 million (€189 million) in the San Francisco-based startup Ample, which currently runs pilot programs with Uber. The start-up aims to develop the battery swap tech especially for fleets, where vehicles are heavily utilized and short charging time is of the essence.

We’ll keep an eye on how things will evolve in the following years. In the next part of this material, we’ll take a look at the conductive charging alternative – maybe this is the real deal for getting electric vehicles on par with their ICE counterparts and making “range anxiety” history.