According to Merriam-Webster, evolution is the scientific theory explaining the appearance of new species and varieties through the action of various biological mechanisms, such as natural selection or genetic mutation.

Coincidentally, a somewhat similar definition can be appropriated to the development of cars, especially in the last two decades or so.

Welcome to the 21st century, a digital age when most of these lovable mechanical chariots we call cars have almost nothing in common with their slightly more analog forebearers despite looking largely the same and not having grown wings or magnetic levitation devices.

Firstly, I realize that a good slice of the more recent technological advancements in the automotive realm has been shaped by a myriad of usually trendy and variable factors rather than the sole influence of engineers and inventors.

The majority of these factors revolve around shifts in market demand and legislative changes or were driven by the influence of financial decision-makers and investors seeking rapid returns.

Developing products that strictly follow market demand, which may or may not have been created by marketing teams belonging to the same companies that build those products, seems like a great way of staying in business and growing, doesn't it?

Well, yes and no, and this wouldn't be the first time marketing ruins a perfectly good thing.

No, I don't subscribe to the notion of a conspiracy designed to inundate our roads and parking spaces with giant crossovers, cars exclusively equipped with automatic transmissions, or appliances on wheels that combine these two characteristics with heavy batteries and electric powertrains. That said, I wouldn't call a conspiracy theorist of the above crazy.

Sure, you will say that some of these vehicles are poised to become self-driving in just a few years (or decades) anyway, so what's the point in crying about the wolf when the sheep themselves are becoming carnivorous.

Until that time arrives - hopefully never at a large scale - many carmakers have already started to gradually lean toward an excessive introduction of features that, among their positives, also diminish the pleasure of driving or simply operating a car.

No, I'm not just talking about the downright invasion of heavy SUVs in every conceivable segment or the slow but inevitable death of the manual transmission, especially since these two developments kind of follow Darwin's theory of natural selection anyway.

My main issue is with a lot of modern cars, no matter their performance, segment, or price range, which have been perpetually filled to the brim with maybe too many driving assistance systems and all kinds of electronic nannies.

While in theory, this part of automotive evolution is of a positive nature, as it has vastly decreased the number of accidents due to human error, in reality, it also brings a fair share of negatives.

I'm not against automotive progress, especially since it includes safer, more efficient, and quicker cars. To give an example, a modern hyper-hatch like the Mercedes-AMG A 45 S is about a second quicker to 62 mph (100 kph) than a friggin' Ferrari F40 supercar.

No, part of the issue is the distancing of the driver from the fundamental act of driving. In the previous example, even your grandma can run circles with the A 45 S around an F40 driven by a racing driver in a drag race.

So, what's the issue, then? Well, the biggest problem lies elsewhere. You see, an increasingly large part of this huge jump in efficiency, safety, and especially performance comes from the advancements in assistance systems. Most of these systems are mainly governed by chips and software, not by a well-engineered mechanical device, such as suspension, steering, or brakes.

The biggest evolution in car design in the last couple of decades hasn't been a new way of building a chassis or a steering system - apart from the materials used in building them, they're still pretty much identical to those of the past.

An increasing number of modern vehicles, including sports cars, derive a significant portion of their performance and excitement through artificial means.

The F40 mentioned before and other similar 'vintage' driver's cars based their handling and behavior on mostly analog mechanical systems developed under the guidance of downright Renaissance men and women.

What is the A 45 S' performance and driving pleasure based on? That's easy: a whole lot of power from a turbo that's almost bigger than its four-cylinder engine and a gimmicky all-wheel-drive system that's electronically controlled and has an artificially induced 'drift mode.' Not to downrate its abilities, but we're still talking about a mainstream hatchback on steroids created by bean counters, not a handful of passionate engineers and designers.

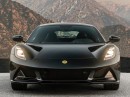

That said, it's not about the cars themselves but the original idea behind their development. You could put the exact same powertrain in a sexy, limited-edition sports car, and it would only improve it, not make it worse. Oh, wait, the Lotus Emira is exactly that, so there is hope!

With that in mind, I understand and welcome the creation of launch-control systems, torque-vectoring differentials, electronic stability systems with 'aggressivity levels', or decouplable AWD systems with 'Drift Modes.'

Those were all developed in the quest of performance, I get it. But what about the joy of driving? How do you think a 400+ HP, FWD-based AWD hatchback would feel behind the wheel whenever you put your foot down if it didn't have an electronically controlled multi-clutch differential governed by software and chips? I'm thinking of the word 'pathetic,' and most of you will probably agree.

In other words, I'm all against the ultimately fake driving pleasure and performance that is the equivalent of using stock CGI in an action movie.

To give a counter-example to this trend of dialing-in handling using software instead of the mind of a great chassis engineer like in the old days, let's take a look at an inexpensive sports car like the Mazda MX-5 Miata.

The tiny roadster, soon to be replaced by a new generation, belongs to a diminishing group of contemporary sports cars that don't rely on sophisticated electronics to deliver speed or the sensation of speed.

Instead, Mazda learned the ways of the old and gave the MX-5 a perfect weight distribution thanks to an engine pushed far back, the mass of a feather, and a manual gearbox to give you all the control you need.

Other automakers have become complacent in the design of sports cars, letting software engineers dictate a significant portion of their performance features instead of relying on chassis engineers.

Don't believe me? Allow me to elaborate. This can be attempted in nearly all modern sports cars that permit you to fully deactivate the electronic stability and engage in a session of "catch the oversteer before you crash," otherwise known as drifting.

Yeah, you can have multiple levels of ESC intervention, and some BMW M cars even score your drift angles in the infotainment system, but isn't that as fake as the engine sounds pumped through the speakers? You're not drifting, the car is - you're just a passenger that's helping it do that.

This becomes evident when pushing a car to its limits on the track and comparing the experience between having all those trick systems on and off. In the latter scenario, the car may give the sensation of driving an overpowered go-kart, and you're no longer the drift king you thought you were with those systems engaged.

Whether we're talking about the amount of understeer or oversteer in a car, weight distribution, or aerodynamics, the result is chassis balance. That sense of control and driving pleasure shouldn't be faked by computer programmers following orders from bean counters but by automotive engineers and racers.

Welcome to the 21st century, a digital age when most of these lovable mechanical chariots we call cars have almost nothing in common with their slightly more analog forebearers despite looking largely the same and not having grown wings or magnetic levitation devices.

Firstly, I realize that a good slice of the more recent technological advancements in the automotive realm has been shaped by a myriad of usually trendy and variable factors rather than the sole influence of engineers and inventors.

The majority of these factors revolve around shifts in market demand and legislative changes or were driven by the influence of financial decision-makers and investors seeking rapid returns.

Developing products that strictly follow market demand, which may or may not have been created by marketing teams belonging to the same companies that build those products, seems like a great way of staying in business and growing, doesn't it?

Well, yes and no, and this wouldn't be the first time marketing ruins a perfectly good thing.

No, I don't subscribe to the notion of a conspiracy designed to inundate our roads and parking spaces with giant crossovers, cars exclusively equipped with automatic transmissions, or appliances on wheels that combine these two characteristics with heavy batteries and electric powertrains. That said, I wouldn't call a conspiracy theorist of the above crazy.

Sure, you will say that some of these vehicles are poised to become self-driving in just a few years (or decades) anyway, so what's the point in crying about the wolf when the sheep themselves are becoming carnivorous.

Until that time arrives - hopefully never at a large scale - many carmakers have already started to gradually lean toward an excessive introduction of features that, among their positives, also diminish the pleasure of driving or simply operating a car.

No, I'm not just talking about the downright invasion of heavy SUVs in every conceivable segment or the slow but inevitable death of the manual transmission, especially since these two developments kind of follow Darwin's theory of natural selection anyway.

My main issue is with a lot of modern cars, no matter their performance, segment, or price range, which have been perpetually filled to the brim with maybe too many driving assistance systems and all kinds of electronic nannies.

While in theory, this part of automotive evolution is of a positive nature, as it has vastly decreased the number of accidents due to human error, in reality, it also brings a fair share of negatives.

I'm not against automotive progress, especially since it includes safer, more efficient, and quicker cars. To give an example, a modern hyper-hatch like the Mercedes-AMG A 45 S is about a second quicker to 62 mph (100 kph) than a friggin' Ferrari F40 supercar.

No, part of the issue is the distancing of the driver from the fundamental act of driving. In the previous example, even your grandma can run circles with the A 45 S around an F40 driven by a racing driver in a drag race.

So, what's the issue, then? Well, the biggest problem lies elsewhere. You see, an increasingly large part of this huge jump in efficiency, safety, and especially performance comes from the advancements in assistance systems. Most of these systems are mainly governed by chips and software, not by a well-engineered mechanical device, such as suspension, steering, or brakes.

The biggest evolution in car design in the last couple of decades hasn't been a new way of building a chassis or a steering system - apart from the materials used in building them, they're still pretty much identical to those of the past.

An increasing number of modern vehicles, including sports cars, derive a significant portion of their performance and excitement through artificial means.

The F40 mentioned before and other similar 'vintage' driver's cars based their handling and behavior on mostly analog mechanical systems developed under the guidance of downright Renaissance men and women.

What is the A 45 S' performance and driving pleasure based on? That's easy: a whole lot of power from a turbo that's almost bigger than its four-cylinder engine and a gimmicky all-wheel-drive system that's electronically controlled and has an artificially induced 'drift mode.' Not to downrate its abilities, but we're still talking about a mainstream hatchback on steroids created by bean counters, not a handful of passionate engineers and designers.

That said, it's not about the cars themselves but the original idea behind their development. You could put the exact same powertrain in a sexy, limited-edition sports car, and it would only improve it, not make it worse. Oh, wait, the Lotus Emira is exactly that, so there is hope!

With that in mind, I understand and welcome the creation of launch-control systems, torque-vectoring differentials, electronic stability systems with 'aggressivity levels', or decouplable AWD systems with 'Drift Modes.'

Those were all developed in the quest of performance, I get it. But what about the joy of driving? How do you think a 400+ HP, FWD-based AWD hatchback would feel behind the wheel whenever you put your foot down if it didn't have an electronically controlled multi-clutch differential governed by software and chips? I'm thinking of the word 'pathetic,' and most of you will probably agree.

In other words, I'm all against the ultimately fake driving pleasure and performance that is the equivalent of using stock CGI in an action movie.

To give a counter-example to this trend of dialing-in handling using software instead of the mind of a great chassis engineer like in the old days, let's take a look at an inexpensive sports car like the Mazda MX-5 Miata.

The tiny roadster, soon to be replaced by a new generation, belongs to a diminishing group of contemporary sports cars that don't rely on sophisticated electronics to deliver speed or the sensation of speed.

Instead, Mazda learned the ways of the old and gave the MX-5 a perfect weight distribution thanks to an engine pushed far back, the mass of a feather, and a manual gearbox to give you all the control you need.

Other automakers have become complacent in the design of sports cars, letting software engineers dictate a significant portion of their performance features instead of relying on chassis engineers.

Don't believe me? Allow me to elaborate. This can be attempted in nearly all modern sports cars that permit you to fully deactivate the electronic stability and engage in a session of "catch the oversteer before you crash," otherwise known as drifting.

Yeah, you can have multiple levels of ESC intervention, and some BMW M cars even score your drift angles in the infotainment system, but isn't that as fake as the engine sounds pumped through the speakers? You're not drifting, the car is - you're just a passenger that's helping it do that.

This becomes evident when pushing a car to its limits on the track and comparing the experience between having all those trick systems on and off. In the latter scenario, the car may give the sensation of driving an overpowered go-kart, and you're no longer the drift king you thought you were with those systems engaged.

Whether we're talking about the amount of understeer or oversteer in a car, weight distribution, or aerodynamics, the result is chassis balance. That sense of control and driving pleasure shouldn't be faked by computer programmers following orders from bean counters but by automotive engineers and racers.