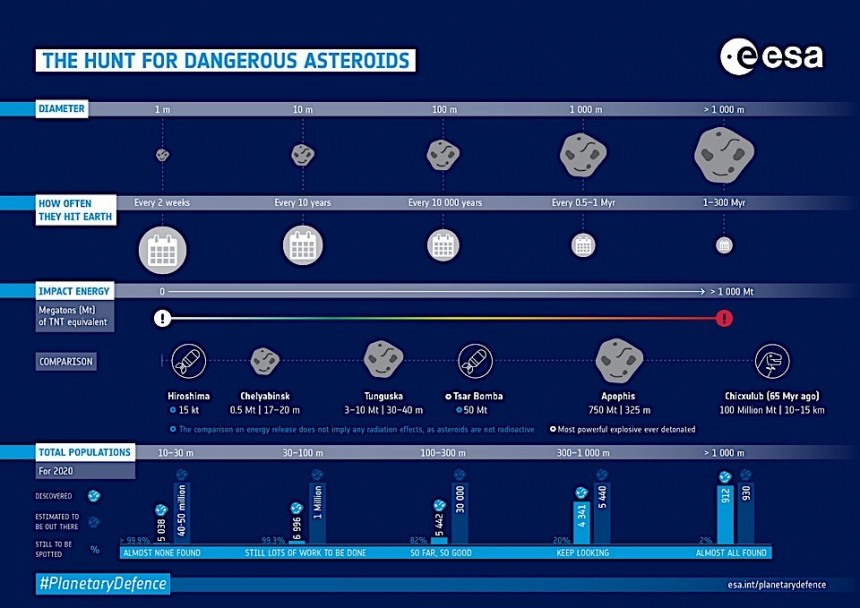

Earlier this week, the world remembered how exactly ten years ago an 18-meter (59 feet) asteroid entered our planet’s atmosphere and detonated over the Russian city of Chelyabinsk. Scores of cameras caught it doing that, and we were all left in awe at the power these things pack, despite their relatively small size.

The Chelyabinsk meteor, as it’s come to be known, exploded with enough force to make it brighter than the Sun for a few short moments. It did so almost 30 km (19 miles) above the ground, but even with such distance involved, it injured close to 1,500 people, both from the blast itself and from debris that was thrown around when the shockwave hit.

The February 2013 detonation was one of the most significant events of this kind we humans have ever experienced firsthand, and the only one to have taken place in the contemporary era over a populated area. Chances are, though, we’ll experience more such detonations, and possibly even impacts, in the years that lie ahead.

One of the biggest problems with asteroids this size is that they’re almost impossible to detect with enough time to spare to get people to safety. Nobody really knows how many of them are out there, nobody really knows their trajectories, and nobody really knows if and when they’ll cross paths with our Earth. And that despite the many tools we now have at our disposal for exactly this purpose.

One of the main issues preventing us from finding potentially dangerous asteroids is the fact many of them come at us from the direction of the Sun. That’s exactly what the one in Chelyabinsk did, approaching under cover of the Sun’s powerful light, and turning into the largest asteroid strike on Earth in over a century.

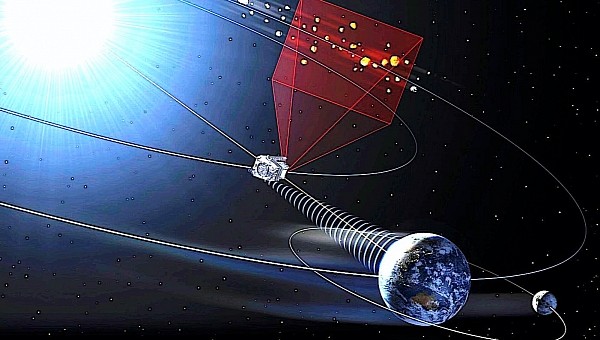

One way around this issue would be placing an observatory in space, at a point from where threats approaching our planet could be detected without the Sun’s glare stopping us from doing that. And that’s exactly the kind of mission the European Space Agency (ESA) is currently planning.

The mission is called NEOMIR, a term which stands for Near Earth Object Mission in the Infrared. As its name partially reveals, it’s centered on a telescope observing its surroundings in infrared.

Not impressive in size, the telescope will rely on a mirror just half a meter in diameter (that’s 1.6 feet, and for comparison, keep in mind the mirror on the James Webb Space Telescope is 6.5 meters/21.6 feet across), sporting a corrected focal plane. Two infrared channels will be covering light in the 5-10 micrometer waveband.

What that means is that NEOMIR will spot asteroids by looking for the heat they emit. This approach makes it possible to detect them regardless of how much sunlight our star throws at the telescope.

All of the above would be relatively useless if NEOMIR were deployed randomly in space. ESA, however, plans to place it at Lagrange point 1 (L1). That’s a place in space between Earth and the Sun where the gravities of the two bodies allow an object to maintain the same position relative to both of them.

From there, the telescope will look on a constant basis at an imaginary ring (one that is impossible to monitor from the surface of our planet) around the Sun, one any asteroid heading for Earth from that direction will have to pass through.

Now, we're pretty confident almost all asteroids larger than one km (0.62 miles) circling our solar system have already been discovered, so those are not the prime targets for NEOMIR. Instead, the telescope will be on the lookout for pieces of space rock slightly larger than the one that exploded over Russia, going as low as 20 meters (66 feet) across.

As per ESA’s estimates, and taking into account the position of the imaginary ring and the telescope itself, asteroids should be spotted at least three weeks in advance. That’s more than enough time to prepare for the impact or detonation, but probably not enough to mount a redirection operation in space.

Even if, in the worst-case scenario, an asteroid should somehow escape NEOMIR’s infrared and only be spotted as it passes L1, that should still give humans a three-day heads up.

With that in mind, it’s safe to say the European mission will probably prove invaluable in our quest to remain safe from space dangers. And it’s another big step taken toward humanity’s stated goal of truly mapping as many as possible of the dangerous asteroids lurking out there in the dark.

At the time of writing, NEOMIR is still in early mission study phase, with the details “currently being fleshed out.” ESA plans to launch it sometime in 2030, on board an Ariane 6 rocket.

When fully deployed, NEOMIR will complement NASA’s NEO Surveyor, which is scheduled to launch in 2026 with the goal of looking for asteroids at least 140 meters (459 feet) across.

The February 2013 detonation was one of the most significant events of this kind we humans have ever experienced firsthand, and the only one to have taken place in the contemporary era over a populated area. Chances are, though, we’ll experience more such detonations, and possibly even impacts, in the years that lie ahead.

One of the biggest problems with asteroids this size is that they’re almost impossible to detect with enough time to spare to get people to safety. Nobody really knows how many of them are out there, nobody really knows their trajectories, and nobody really knows if and when they’ll cross paths with our Earth. And that despite the many tools we now have at our disposal for exactly this purpose.

One of the main issues preventing us from finding potentially dangerous asteroids is the fact many of them come at us from the direction of the Sun. That’s exactly what the one in Chelyabinsk did, approaching under cover of the Sun’s powerful light, and turning into the largest asteroid strike on Earth in over a century.

The mission is called NEOMIR, a term which stands for Near Earth Object Mission in the Infrared. As its name partially reveals, it’s centered on a telescope observing its surroundings in infrared.

Not impressive in size, the telescope will rely on a mirror just half a meter in diameter (that’s 1.6 feet, and for comparison, keep in mind the mirror on the James Webb Space Telescope is 6.5 meters/21.6 feet across), sporting a corrected focal plane. Two infrared channels will be covering light in the 5-10 micrometer waveband.

What that means is that NEOMIR will spot asteroids by looking for the heat they emit. This approach makes it possible to detect them regardless of how much sunlight our star throws at the telescope.

From there, the telescope will look on a constant basis at an imaginary ring (one that is impossible to monitor from the surface of our planet) around the Sun, one any asteroid heading for Earth from that direction will have to pass through.

Now, we're pretty confident almost all asteroids larger than one km (0.62 miles) circling our solar system have already been discovered, so those are not the prime targets for NEOMIR. Instead, the telescope will be on the lookout for pieces of space rock slightly larger than the one that exploded over Russia, going as low as 20 meters (66 feet) across.

As per ESA’s estimates, and taking into account the position of the imaginary ring and the telescope itself, asteroids should be spotted at least three weeks in advance. That’s more than enough time to prepare for the impact or detonation, but probably not enough to mount a redirection operation in space.

With that in mind, it’s safe to say the European mission will probably prove invaluable in our quest to remain safe from space dangers. And it’s another big step taken toward humanity’s stated goal of truly mapping as many as possible of the dangerous asteroids lurking out there in the dark.

At the time of writing, NEOMIR is still in early mission study phase, with the details “currently being fleshed out.” ESA plans to launch it sometime in 2030, on board an Ariane 6 rocket.

When fully deployed, NEOMIR will complement NASA’s NEO Surveyor, which is scheduled to launch in 2026 with the goal of looking for asteroids at least 140 meters (459 feet) across.