‘Aerodynamics are for people who can’t build engines.’ This outrageous saying belongs to the Godfather of automotive arrogance, and horsepower cowboy Enzo Ferrari, and it was whiplashed as a response to one of his drivers. In 1960, the Prancing Horse dominated the racing spectrum. Paul Frère, one of Scuderia’s drivers, inquired about the not-so-slipstreaming windshield of his 250 Testa Rossa, which had a capped top speed at Le Mans.

Old man Enzo was so confident in the superiority of his motoring creations that he discarded the car's aerodynamics as unnecessary to beat the competition. Then Ford knocked the winner’s champagne bottle out of the Italian’s hands in 1966 (and the following three Le Mans races). Powertrains alone weren’t enough to take checkered flags.

Ferrari was wrong – it wasn’t his only time – and carmakers had relied on cheating air resistance long before 1960. Chrysler developed the Airflow in the early 30s using a wind tunnel and turned to space engineers to shape out the famous winged warriors of 1969 and 1970 (the Dodge Charger Daytona and Plymouth Road Runner Superbird).

Aerodynamics isn’t just for going fast(er/est); it’s also for burning less fuel/draining less battery power over a given distance at a given speed. In other words, money- and planet-saving purposes. However, certain speed lords discard money out of the equation entirely because they build cars for filthy-rich customers. Summarized in a single word, this paragraph would be spelled like this: B u g a t t i.

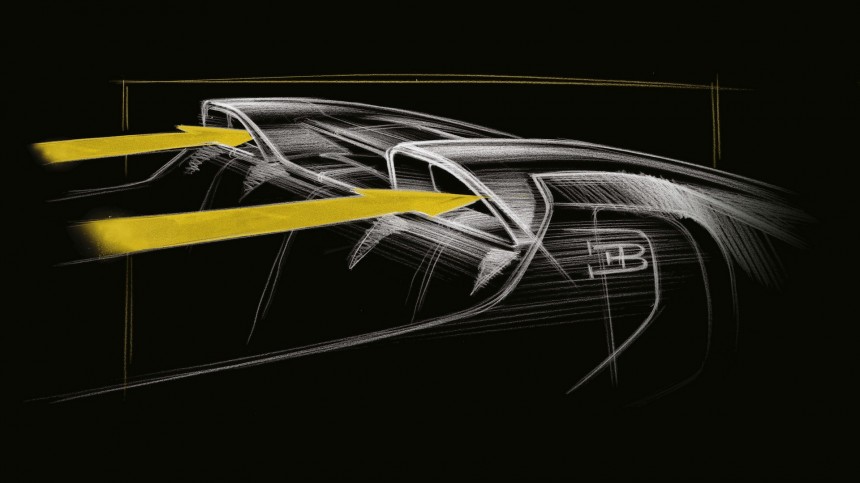

Bugatti doesn’t simply make obscenely expensive and fast automobiles by adding more cylinders to the engines (although it sure seems like it if we look at the last two decades). The absurdly rapid machines rely primarily on aerodynamics to push the land speed milestone ever higher. And splitting the air at 400 kph (250 mph) is vital when there’s no roof over the two occupants.

This year, the W16 Mistral will begin delivery to the 99 customers who coughed up the €5 million ($5.4 million at the February 2024 exchange rate) for one. The hypercar is the final bow to the iconic sixteen-cylinder engine that debuted in 2004 on the ungodly Veyron.

Ranging in power from 1,000 to 1,618 PS (986 to 1,600 hp), depending on its Bugatti application, the famous W16 engine bids farewell to the Combustion Age in the W16 Mistral open-top bullet. The car was built with aerodynamics as its foundation, with digital simulations allowing the teams of engineers and designers to direct the air streams with microscopic accuracy.

To be fair, it wasn’t as much as getting to that speed of 420 kph (261 mph) that was the challenge (the Chiron Super Sport 300+ raised the bar at over 300 mph). The goal was to get there without shattering the driver’s and passenger’s eardrums from either noise or air pressure.

The brainiacs fiddled with the Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) software before going to the analog wind tunnel. The result was a profile that deviates airflow around and over the cabin and straight into the gaping intakes for the engine and its lubricant, transmission, and coolant radiators. That’s the main reason for the car’s reshaped horseshoe grille. The widened center-front intake forces air toward the central radiator, thus cooling the quad-turbo eight-liter W16 monster.

The exhaust-gasses-actuated compressors get air directly from the ram induction inlets situated less than eight inches (20 cm) behind the occupants’ heads. Despite this closeness, the passengers are undisturbed by the currents of air being scooped into the engine bay. Connecting the two carbon-fiber-enforced ducts, the spoiler channels air to the rear wing for optimal downforce.

The air intakes also serve as crash bars thanks to their super-strong carbon core. Each ‘humpback’ air tunnel is strong enough to support the entire car's weight in case of a rollover. When pushing speeds that would send an airplane flying, the W16 heart of the Mistral produces tremendous amounts of heat – the exhaust gasses reach 980°C (1,796°F). It takes an ultra-performing thermodynamic design to keep it running at full throttle.

The hot air exits the radiators through ducts in the rear. The low-pressure zone effectively sucks the air out of the car through its iconic taillights. The air-taming games start right at the front of the Mistral, with the headlamps design funneling air through the lights and out through the wheel arch to optimize aerodynamic drag. The two side intakes beneath the main grille channel cold air to the intercoolers.

When the final example leaves the Molsheim Atelier, it will carry with it the last of the legendary W16 engines that came to be over two decades ago when the Bugatti Veyron was conceived. Over the course of two decades, the engineers have managed to upgrade the colossal powerplant by over 60% in terms of raw output.

The original speed-record breaker motor installed in the Veyron scored 1,001 PS on the dyno from the first try in 2002. In 2019, the Chiron Super Sport 300+ made a low fly-by at 304.773 mph (490.484 kph), raising the bar for production cars to peaks that have yet to be conquered by the other top-tier players in the fast-driving business.

Ferrari was wrong – it wasn’t his only time – and carmakers had relied on cheating air resistance long before 1960. Chrysler developed the Airflow in the early 30s using a wind tunnel and turned to space engineers to shape out the famous winged warriors of 1969 and 1970 (the Dodge Charger Daytona and Plymouth Road Runner Superbird).

Aerodynamics isn’t just for going fast(er/est); it’s also for burning less fuel/draining less battery power over a given distance at a given speed. In other words, money- and planet-saving purposes. However, certain speed lords discard money out of the equation entirely because they build cars for filthy-rich customers. Summarized in a single word, this paragraph would be spelled like this: B u g a t t i.

This year, the W16 Mistral will begin delivery to the 99 customers who coughed up the €5 million ($5.4 million at the February 2024 exchange rate) for one. The hypercar is the final bow to the iconic sixteen-cylinder engine that debuted in 2004 on the ungodly Veyron.

Ranging in power from 1,000 to 1,618 PS (986 to 1,600 hp), depending on its Bugatti application, the famous W16 engine bids farewell to the Combustion Age in the W16 Mistral open-top bullet. The car was built with aerodynamics as its foundation, with digital simulations allowing the teams of engineers and designers to direct the air streams with microscopic accuracy.

The brainiacs fiddled with the Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) software before going to the analog wind tunnel. The result was a profile that deviates airflow around and over the cabin and straight into the gaping intakes for the engine and its lubricant, transmission, and coolant radiators. That’s the main reason for the car’s reshaped horseshoe grille. The widened center-front intake forces air toward the central radiator, thus cooling the quad-turbo eight-liter W16 monster.

The exhaust-gasses-actuated compressors get air directly from the ram induction inlets situated less than eight inches (20 cm) behind the occupants’ heads. Despite this closeness, the passengers are undisturbed by the currents of air being scooped into the engine bay. Connecting the two carbon-fiber-enforced ducts, the spoiler channels air to the rear wing for optimal downforce.

The hot air exits the radiators through ducts in the rear. The low-pressure zone effectively sucks the air out of the car through its iconic taillights. The air-taming games start right at the front of the Mistral, with the headlamps design funneling air through the lights and out through the wheel arch to optimize aerodynamic drag. The two side intakes beneath the main grille channel cold air to the intercoolers.

When the final example leaves the Molsheim Atelier, it will carry with it the last of the legendary W16 engines that came to be over two decades ago when the Bugatti Veyron was conceived. Over the course of two decades, the engineers have managed to upgrade the colossal powerplant by over 60% in terms of raw output.

The original speed-record breaker motor installed in the Veyron scored 1,001 PS on the dyno from the first try in 2002. In 2019, the Chiron Super Sport 300+ made a low fly-by at 304.773 mph (490.484 kph), raising the bar for production cars to peaks that have yet to be conquered by the other top-tier players in the fast-driving business.