Does anyone else get the impression Stratolaunch is cheating a little bit when it comes to its "largest aircraft ever built by wingspan" title? Well, it's essentially two airliner fuselages fused together, is it not? One can only assume that's just semantics when there's a man or woman in a suit from the Guinness Book of World Records waiting with a placard standing around. But what tons of people probably don't know is the Stratolaunch concept is far from new. As far back as the mid-1970s, a man named John M. Conroy had the same idea. This is the story of the Conroy Vitrus, the Stratolaunch's long-forgotten, unbuilt ancestor.

In truth, John Michael Conroy is a man who deserves his own spotlight feature at some point. Born in Buffalo, New York, on December 14th, 1920, Conroy earned his aerial stripes as a B-17 Flying Fortress bomber pilot during World War II. After 12 years as an airline pilot and a bit of time flying with the California Air National Guard after the war, Conroy developed a keen sense of design for novel airplanes he'd dreamed up in his head. In his spare time, he'd even jot down rough sketches of what these airplanes might look like. It was through a conversation Conroy held one night with a fellow aviation entrepreneur and close friend, Lee Mansdorf, about transporting rocket booster stages for NASA via the air that spawned Conroy's first aircraft design.

Known the world over today as the Aero Spacelines Pregnant Guppy, the iconic outsized cargo plane derived from a standard Boeing 377 airliner is still one of the most instantly recognizable silhouettes of any airframe built in the 20th century. Thus began John Conroy's ascent to the undisputed king of outsized cargo aircraft, a role he further fulfilled by designing follow-ups to the Pregnant Guppy. Dubbed the Mini Guppy and the Super Guppy, respectively, the latter of the two is still in service today under contract with NASA. Conroy even developed a penchant for engine swaps during this time, creating special turboprop-engined conversions of icons like the Grumman Albatross flying boat, the Cessna 337 Skymaster, and even the iconic Douglas DC-3 airliner.

In 1968, John Conroy set off on his own and founded his own eponymously-named aircraft manufacturing business with his own hangar at Santa Barbara Airport in California. Though his first product was another outsized cargo liner based on a Canadair CL-44 and dubbed the Conroy Skymonster, John Conroy would soon devise a far more radical and special design for a rapidly approaching new issue. As NASA geared up to manufacture the new Space Shuttle orbiters, the question of how to transport this proverbial flying brick around became a consistent thorn in their side. Of course, the Space Shuttle was originally designed with turbofan engines integrated into its airframe. But their deletion from the final product made this issue one of the most pressing matters of the Space Shuttle program outside the orbiter itself.

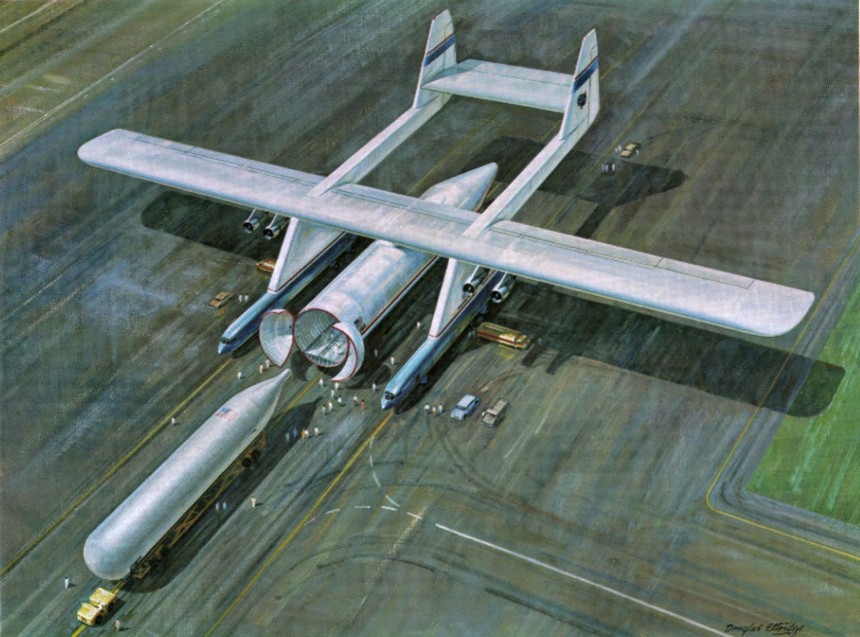

It was from this problem that John Conroy first devised the idea for a new aircraft he simply called the Vitrus. Even from just a cursory glance, it's hard not to look at rough sketches of the Conroy Vitrus and not immediately be reminded of the modern-day Scaled Composites Stratolaunch it bares a striking resemblance to. Both designs utilize twin fuselages fused together via a common wing and multiple engines to transport high-priority cargo, usually a spacecraft of some kind, which can't get off the ground under their own power. But a closer inspection reveals a few key differences between the two aircraft.

Firstly, Conroy's Vitrus was set to utilize a massive twin-boom arrangement and four Pratt & Whitney JT9D engines from the Boeing 747-100. Meanwhile, the Stratolaunch's twin-fuselage pods use separate rudder and elevator controls with six Pratt & Whitney PW4000s from the newer 747-400 and Airbus A330. Unlike the Stratolaunch, whose twin fuselages are of an entirely new design, Conroy hoped to save considerable costs by the Vitrus' fuselages from the bodies of two Boeing B-52 Stratofortress bombers joined together via a common wing.

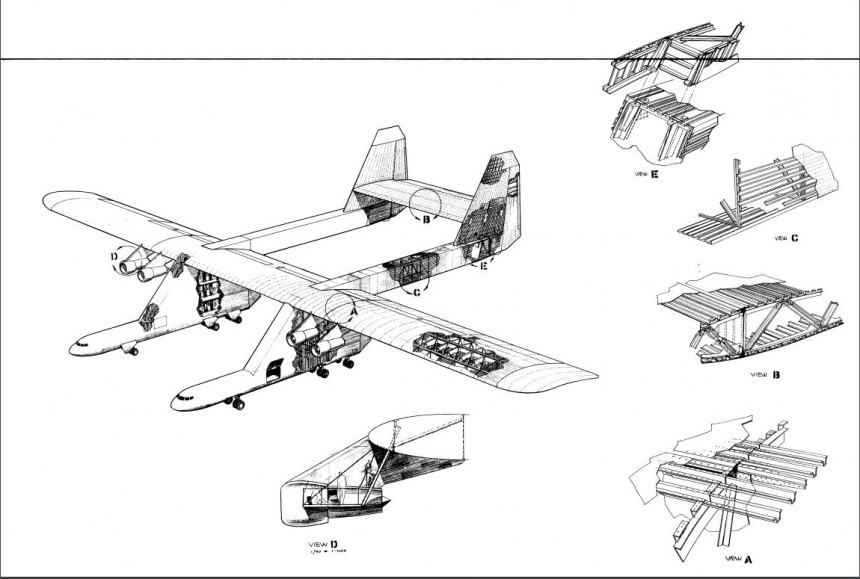

Both the Stratolaunch and the Vitrus were designed to carry cargo underneath the shared wing truss, which joins both fuselages together. In the case of the Vitrus, the airframe would have been tailor-made specifically to accommodate NASA's Space Shuttle orbiters with the ability to take on other projects whenever necessary. With projected dimensions of a scarcely-believable 450 feet (140 m), the Vitrus would have even had the Stratolaunch on the ropes in terms of raw scale. Had the Vitrus been built, it would have been a full 65 feet (19.8 m) longer in its wingspan than Stratolaunch, and that's the largest aircraft ever built by a country mile.

With help from NASA's Langley Research Center in Virginia, John Conroy began developing the finer details of the Vitrus concept. Everything from the Space Shuttle orbiters themselves to its massive external fuel tank and solid rocket boosters were slated to be hauled under the Vitrus' undercarriage. There were even plans for a special cargo pod to accommodate just about any outsized cargo imaginable. The new design was even allowed to undergo wind-tunnel testing at the same facility at Langley where the Space Shuttle's design was once tested. On paper, at least, Conroy appeared to have the formula for an all-time classic aircraft. A vehicle that could reasonably be described as one of the most important machines in the history of aviation.

But unfortunately, NASA appeared to have other plans in mind. For one thing, Conroy's Vitrus wasn't the only proposal for a Space Shuttle transport vehicle. Established juggernauts like Lockheed and Boeing also submitted design proposals for the same NASA initiative. One such competitor was a twin-fuselage variant of the Lockheed C-5 Galaxy similar to the design of the Vitrus, but also a more traditional Boeing 747 airframe modified to carry the Shuttle on its roof rather than its undercarriage. It was this design, named the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA), which NASA chose to ferry its prized spaceplanes around for the next 35 years. Only stopping once the Shuttle program came to an end in 2011.

Meanwhile, John Conroy, not ready to give up quite yet after his rejection by NASA, still had a trick or two up his sleeve. If NASA wasn't going to take advantage of his design, then perhaps the private sector would. With a few modifications to the original design, Conroy proposed a civil cargo liner variant based upon the Vitrus, internally named the Colossus and aimed at much the same market space that Stratolaunch services to great effect today. But sadly, private commercial spaceflight simply wasn't possible in the mid-1970s the same way it is today, and not a single private investor showed an interest in the Colossus. By the end of the 1970s, the Vitrus program had been all but abandoned.

Tragically, John Conroy died of colon cancer in December 1979, his work with the Vitrus unfulfilled. But in defense of one of the most skilled aircraft designers of the second half of the 20th century, Conroy was absolutely onto something when he designed the Vitrus. As is self-evident by the success of the Stratolaunch, there indeed is a profitable market for twin-fuselage, super heavy transport aircraft that spend most of their service life launching spaceplanes for high-paying aerospace contractors. From this point of view, the only great sin the Conroy Vitrus ever committed was being designed before the industry it was meant to cater to had gotten off the ground.

It's likely because John Conroy was so forward-thinking in his aircraft designs that Scaled Composites could take the same basic idea, modernize it just a little bit, and make its way into the history books. If you ask us, don't be surprised if more aircraft of this configuration take to the skies sometime soon. If they do, you can thank Mr. Conroy for getting the ball rolling.

Known the world over today as the Aero Spacelines Pregnant Guppy, the iconic outsized cargo plane derived from a standard Boeing 377 airliner is still one of the most instantly recognizable silhouettes of any airframe built in the 20th century. Thus began John Conroy's ascent to the undisputed king of outsized cargo aircraft, a role he further fulfilled by designing follow-ups to the Pregnant Guppy. Dubbed the Mini Guppy and the Super Guppy, respectively, the latter of the two is still in service today under contract with NASA. Conroy even developed a penchant for engine swaps during this time, creating special turboprop-engined conversions of icons like the Grumman Albatross flying boat, the Cessna 337 Skymaster, and even the iconic Douglas DC-3 airliner.

In 1968, John Conroy set off on his own and founded his own eponymously-named aircraft manufacturing business with his own hangar at Santa Barbara Airport in California. Though his first product was another outsized cargo liner based on a Canadair CL-44 and dubbed the Conroy Skymonster, John Conroy would soon devise a far more radical and special design for a rapidly approaching new issue. As NASA geared up to manufacture the new Space Shuttle orbiters, the question of how to transport this proverbial flying brick around became a consistent thorn in their side. Of course, the Space Shuttle was originally designed with turbofan engines integrated into its airframe. But their deletion from the final product made this issue one of the most pressing matters of the Space Shuttle program outside the orbiter itself.

It was from this problem that John Conroy first devised the idea for a new aircraft he simply called the Vitrus. Even from just a cursory glance, it's hard not to look at rough sketches of the Conroy Vitrus and not immediately be reminded of the modern-day Scaled Composites Stratolaunch it bares a striking resemblance to. Both designs utilize twin fuselages fused together via a common wing and multiple engines to transport high-priority cargo, usually a spacecraft of some kind, which can't get off the ground under their own power. But a closer inspection reveals a few key differences between the two aircraft.

Both the Stratolaunch and the Vitrus were designed to carry cargo underneath the shared wing truss, which joins both fuselages together. In the case of the Vitrus, the airframe would have been tailor-made specifically to accommodate NASA's Space Shuttle orbiters with the ability to take on other projects whenever necessary. With projected dimensions of a scarcely-believable 450 feet (140 m), the Vitrus would have even had the Stratolaunch on the ropes in terms of raw scale. Had the Vitrus been built, it would have been a full 65 feet (19.8 m) longer in its wingspan than Stratolaunch, and that's the largest aircraft ever built by a country mile.

With help from NASA's Langley Research Center in Virginia, John Conroy began developing the finer details of the Vitrus concept. Everything from the Space Shuttle orbiters themselves to its massive external fuel tank and solid rocket boosters were slated to be hauled under the Vitrus' undercarriage. There were even plans for a special cargo pod to accommodate just about any outsized cargo imaginable. The new design was even allowed to undergo wind-tunnel testing at the same facility at Langley where the Space Shuttle's design was once tested. On paper, at least, Conroy appeared to have the formula for an all-time classic aircraft. A vehicle that could reasonably be described as one of the most important machines in the history of aviation.

But unfortunately, NASA appeared to have other plans in mind. For one thing, Conroy's Vitrus wasn't the only proposal for a Space Shuttle transport vehicle. Established juggernauts like Lockheed and Boeing also submitted design proposals for the same NASA initiative. One such competitor was a twin-fuselage variant of the Lockheed C-5 Galaxy similar to the design of the Vitrus, but also a more traditional Boeing 747 airframe modified to carry the Shuttle on its roof rather than its undercarriage. It was this design, named the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA), which NASA chose to ferry its prized spaceplanes around for the next 35 years. Only stopping once the Shuttle program came to an end in 2011.

Tragically, John Conroy died of colon cancer in December 1979, his work with the Vitrus unfulfilled. But in defense of one of the most skilled aircraft designers of the second half of the 20th century, Conroy was absolutely onto something when he designed the Vitrus. As is self-evident by the success of the Stratolaunch, there indeed is a profitable market for twin-fuselage, super heavy transport aircraft that spend most of their service life launching spaceplanes for high-paying aerospace contractors. From this point of view, the only great sin the Conroy Vitrus ever committed was being designed before the industry it was meant to cater to had gotten off the ground.

It's likely because John Conroy was so forward-thinking in his aircraft designs that Scaled Composites could take the same basic idea, modernize it just a little bit, and make its way into the history books. If you ask us, don't be surprised if more aircraft of this configuration take to the skies sometime soon. If they do, you can thank Mr. Conroy for getting the ball rolling.