We go through life without duly thanking the thousands of people that made it easier and more comfortable. Just think about electric lamps and the telephone. How many times were you grateful to Thomas Edison or Graham Bell? What about now long-lost names of those who invented bricks, cement, plumbing, clothes, and the long etcetera we now take for granted? Anyone reading this had the privilege to live while John B. Goodenough was still around us. On June 25, he passed away – exactly a month from celebrating 101 years.

If you have not connected the dots about who this man was yet, ask your laptop, cell phone, tablet, and even your battery electric vehicle (BEV) more about him. They only work because of what Goodenough developed based on previous work from M. Stanley Whittingham. Before lithium-ion rechargeable cells made their commercial premiere with Sony in 1991, Akira Yoshino made some improvements that are also considered crucial to lithium-ion cells. These guys created the lithium-ion battery that we know today, an achievement that gave them the 2019 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Goodenough was 97, which made him the oldest person ever to receive the award.

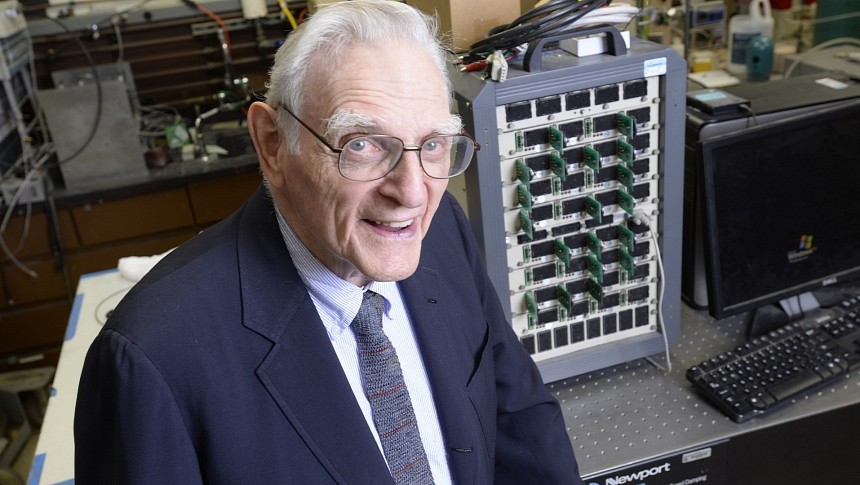

According to the University of Texas, "Goodenough identified and developed the critical cathode materials that provided the high-energy density needed to power electronics such as mobile phones, laptops, and tablets, as well as electric and hybrid vehicles." That happened around 1979 – when he and his team discovered that "by using lithium cobalt oxide as the cathode of a lithium-ion rechargeable battery, it would be possible to achieve a high density of stored energy with an anode other than metallic lithium."

It is curious to see the university mention that the battery had a high energy density when current research efforts want to improve what that original lithium-ion cell offered. That needs more historical context: these batteries were indeed much superior to everything that was available at the time. Contrary to his own name, that never stopped Goodenough to keep searching for improvements.

One of his most recent scientific creations was a glass battery developed in 2016 in partnership with Maria Helena Braga, a Portuguese researcher from the University of Porto. Although it is called that, its main breakthrough is a glass electrolyte that has the potential to create safer and more affordable solid-state batteries. Several researchers said the Braga-Goodenough papers contained basic calculation mistakes. At some point, Braga and Goodenough said the glass battery would self-charge, which was received with a lot of skepticism.

While people were discussing this, the two researchers sold their patents in 2020 to Hydro-Quebec. The Canadian hydroelectric power company committed to delivering a commercial version of that battery in around two years. Matthew Lacey, a scientist from Uppsala University, bet that people would forget about this new cell because it was based on "claims that are completely unsupportable." Three years later, either Lacey was right, or Hydro-Quebec is facing some delays.

Goodenough was born on July 25, 1922, in Jena, Germany. His parents were American, and he got back to the US in his childhood. In 1944, the scientist achieved a degree in mathematics from Yale University, going to the Army shortly after that to serve as a meteorologist. After he got back, he completed a master's degree and a PhD in Physics from the University of Chicago in 1952. Goodenough started working for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the same year and only left 24 years later. In 1954, the scientist married Irene Wiseman, and they stayed together until she died in 2016. They did not have children.

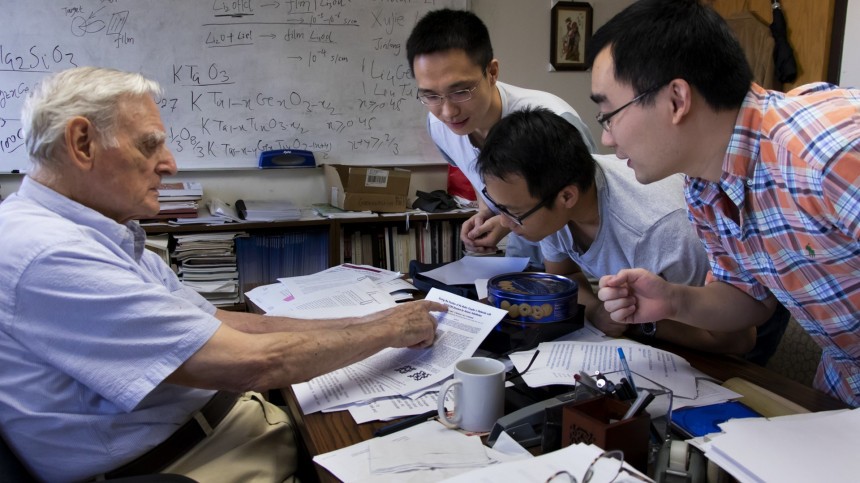

At MIT, Goodenough helped develop random-access memory (RAM) – yes, that one you have in your computer and in anything that runs software. He also came up with concepts of cooperative orbital ordering, also known as a cooperative Jahn–Teller distortion, among other critical scientific achievements. After leaving MIT, the scientist joined the University of Oxford, where he headed the Inorganic Chemistry Laboratory until he joined the University of Texas in 1986. In interviews when he received the Nobel Prize, Goodenough said that he would not have to retire in Texas. He worked there until he was 98.

His colleagues remember him for his characteristic laugh – which you can check in the video below – and for being a humble genius. They also said he was a fantastic mentor for new scientists. Work certainly helped him live that much, even if his body may have failed him before he felt he had done all he could. For a man who contributed so much to science, I just hope he did not feel frustrated he couldn't do more. May this brilliant man forgive me for the pun wherever he is, but what he achieved was more than Goodenough. Above all, may he know we are grateful for everything he did.

According to the University of Texas, "Goodenough identified and developed the critical cathode materials that provided the high-energy density needed to power electronics such as mobile phones, laptops, and tablets, as well as electric and hybrid vehicles." That happened around 1979 – when he and his team discovered that "by using lithium cobalt oxide as the cathode of a lithium-ion rechargeable battery, it would be possible to achieve a high density of stored energy with an anode other than metallic lithium."

One of his most recent scientific creations was a glass battery developed in 2016 in partnership with Maria Helena Braga, a Portuguese researcher from the University of Porto. Although it is called that, its main breakthrough is a glass electrolyte that has the potential to create safer and more affordable solid-state batteries. Several researchers said the Braga-Goodenough papers contained basic calculation mistakes. At some point, Braga and Goodenough said the glass battery would self-charge, which was received with a lot of skepticism.

Goodenough was born on July 25, 1922, in Jena, Germany. His parents were American, and he got back to the US in his childhood. In 1944, the scientist achieved a degree in mathematics from Yale University, going to the Army shortly after that to serve as a meteorologist. After he got back, he completed a master's degree and a PhD in Physics from the University of Chicago in 1952. Goodenough started working for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the same year and only left 24 years later. In 1954, the scientist married Irene Wiseman, and they stayed together until she died in 2016. They did not have children.

His colleagues remember him for his characteristic laugh – which you can check in the video below – and for being a humble genius. They also said he was a fantastic mentor for new scientists. Work certainly helped him live that much, even if his body may have failed him before he felt he had done all he could. For a man who contributed so much to science, I just hope he did not feel frustrated he couldn't do more. May this brilliant man forgive me for the pun wherever he is, but what he achieved was more than Goodenough. Above all, may he know we are grateful for everything he did.