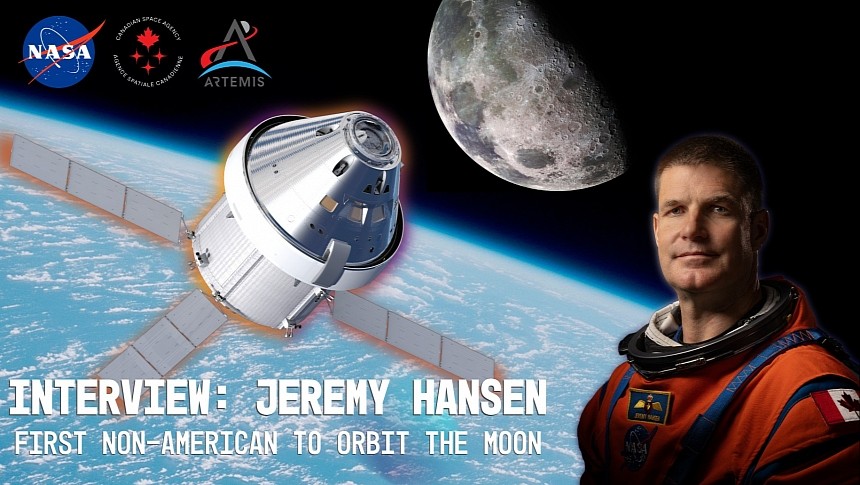

We bet you never thought Americans would finally return to the Moon, let alone a national of some other country. But if you haven't been paying attention recently, and no shame if you haven't, the future of human-crewed spaceflight will look remarkably different than it did in the 60s. A diverse mix from across the globe will soon head to deep space, and we at autoevolution had the distinction of talking one-on-one with the man chosen to be the first non-American to orbit the Moon.

This is Canadian Space Agency (CSA) astronaut Col. Jeremy Hansen, Mission Specialist for Artemis II. Before being recruited by the CSA, he was a Royal Canadian Air Force CF-18 fighter pilot. There was no guarantee that Mr. Hansen had the time to conversate with a re-incarnated Walter Cronkite, let alone with us. But in a gesture that won't soon be forgotten, the fine folks in the CSA's media relations team were able to book a 30-minute Zoom meeting right before Hansen was due to leave from a conference in Washington D.C. to get on a flight back to Houston.

But for all you hear about stories of Apollo and Space Shuttle astronauts not getting too emotional until they're strapped into their spacecraft mere minutes from launch, Hansen is doing everything in his power to take things in stride and enjoy the ride while it lasts. "I can relate to that sentiment, although I don't think I could necessarily answer whether it's going to be like that or not for me until I get all the way through it," Hansen said of his upcoming Artemis II launch, only ten or so months away at the time of this interview. "I do have these sorts of moments of realization along the way, and for me, there's been a lot of emotions associated with it, especially in the beginning, it was very humbling."

With Mission Commander Reid Weisman, Mission Specialist Christina Koch, and the Orion space capsule's Pilot, Victor Glover, alongside him, Artemis II's crew is due to bring the first person of color, the first woman, and the first non-American national to space for the first time in human history. As far as the non-American astronaut side of things goes, none of it would've been possible had it not been for a piece of international collaboration known as the Artemis Accords.

Signed by Canada in October 2020, this non-binding international agreement will soon permit astronauts from 33 signatories and counting from across Europe, Asia, Oceania, and the Americas to share in the spoils of a new-age space race quite unlike the original. But the Artemis Accords is not a free ride on NASA spacecraft to whichever countries align ideologically with the United States. In fact, the Artemis program and the Artemis Accords are two separate entities totally independent of one another.

Every signatory nation, large or small, is expected to make a material contribution on journeys to the Moon and, eventually, Mars and beyond. For Canada to punch the first international ticket to the Moon, its contribution to NASA's ambitions in deep space was nothing short of substantial. "We at the CSA committed to a partnership with NASA, as did the ESA and Japan in respect to the Lunar Gateway station. We said we'd provide a third generation of space robotics in the Canadarm3 for Gateway, and in exchange for that, we negotiated two flights to deep space, of which Artemis II is the first."

Hansen and his crew will be distinguished guests aboard a slew of new spacecraft hardware benefiting from the latest advancements in aeronautical engineering, computing performance, and launch vehicle hardware. From the 322-foot (98.1-m) tall SLS launch vehicle with 8.8 million lbs of thrust at its disposal at liftoff to the ESA's European Service module, whose engine, battery cells, and life support systems form the heart and soul of the Artemis program, there's no shortage of astonishing technology at Hansen and company's disposal once they're up in space.

But to many, no other vehicle involved with Artemis II is more noteworthy than Lockheed Martin's Orion space capsule. With a striking silhouette reminiscent of an upsized Apollo Command Module, Orion is 50 percent more voluminous and can comfortably accommodate a fourth crew member as a result. As Orion demonstrated during its first trip around the Moon during the un-crewed Artemis I mission, NASA's priced space capsule's autopilot can do the job all on its own with ease.

But flight computers can never fully replace a human hand behind the stick when astronauts are allowed on board. With this in mind, intensely studying and becoming acclimated to Orion's intricate hardware is still just as vital as it was during the Apollo program. As Canada's first part-time resident of deep space can attest to, that's one heck of an intricate process. "We've been spending a lot of time learning everything about Orion," Hansen said of his duties while training at the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

Like Apollo, the Artemis program employs contractors and personnel from all walks of life across 50 U.S. States and many countries abroad. This list of worthy names could go on for ages, but Jeremy was more than happy to name some key players. "We have an enormous team of people that help us; Lockheed certainly is a part of that. We have flight controllers at NASA who actually controlled Artemis I, who were at Mission Control, sending the commands and making those decisions. But we have experts from each individual domain and discipline of the vehicle from Mission Control who come and spend time with us, teaching us each individual system. Then, they'll put us through simulator sessions to work with each system."

More than 29,000 total hours of simulator time took place across 15 different NASA-run simulation facilities during the Apollo program. In time, Artemis II's crew will begin racking up hours in their own simulators. Through cutting-edge, real-time simulation of every feasible scenario at each point in the ten-day mission, each of the four crew will cram what once took a year or more of sim time into just under ten months. This means for Hansen and company, the grueling work ahead has a no-doubt historic end prize.

"I actually haven't done an integrated sim with Mission Control yet, I'm still sort of learning the vehicle. But in the new year, we'll be getting to that point where we'll be simulating aspects of the mission, putting in failures, having to overcome the failures while working with Mission Control. All of that is still evolving," Hansen said of the break-neck pace for Artemis II. With its launch date of September 2025, there's no time to lose. While the astronauts train up, so too will every other aspect of the mission, every space suit, every valve, computer, and every line of code, be developed in parallel.

"We're putting together a training flow that the next astronauts will follow, but we're sort of making that up as we go along. As things change, we'll just adapt our understanding," Hansen said of the relaxed yet undeniably thoughtful approach to Artemis II's mission development over the next year. "We sort of learn along with the developers, if you will." Of course, you'd hope Artemis II's crew would be doing plenty of scientific experiments while in transit to and in orbit around the Moon. The lunar dark side hasn't been observed by human eyes since Apollo 17 left the Moon's orbit back in 1973, after all.

But because Artemis II is the first human-crewed mission for a wholly bespoke new spacecraft, the name of the game for the mission is oriented more around optimizing Orion's systems for future lunar landings rather than conducting much hard science. "Science is a driving factor behind our reason to go back to the Moon, and we'll do as much science as we can on Artemis II," Hansen said of his upcoming mission. "But to be fair, we're quite limited because it's the first test flight, and we have a lot of mass restrictions and volume restrictions."

With so little of Artemis' key infrastructure ready by the time the second mission launches, including the Gateway space station, a restriction on its ability to conduct science makes sense. But in Jeremy Hansen's own words, the strongest data points of the entire mission could be the crew themselves. "The biggest research facilities will be us, the four humans on board. So that will enable some really fascinating research opportunities. That will start a new dataset for human research in deep space. Speaking of the dark side of the Moon, because they wanted the near side lit, large portions of the dark side were typically dark during the Apollo program. Depending on when we launch, we may be able to see parts of the dark side of the Moon in a lighted condition that the Apollo astronauts never saw."

Under the right conditions, it's possible the astronauts on board could observe these portions of the lunar dark side in ways nothing other than a satellite has ever seen, let alone human eyes. "The geologists have explained to us that the human eye observation is very interesting to them. Apollo astronauts did have some observations that caught the eye that you don't necessarily pick up in a satellite observation, and they were very interested in what we might observe. We don't know if we will, but we definitely will be looking, and that's fun to think about."

With so many achievements and footnotes soon to pass in the leadup to Artemis II's launch, many questions about the intricate details still need to be answered. Or, at least, they'll be answered very soon. But Jeremy Hansen's previous career as a fighter jet jockey for the RCAF is just as fascinating as his work as an astronaut. As a veteran pilot of Canada's decades-long premiere twin-engine jet fighter, the CF-18 Hornet, Hansen is especially qualified to explain why this 40-year-old airframe continues to dominate Canadian airspace.

"I think what's important to understand is that fighter jets evolve over time, even though initial production may have started that long ago. You may have an airframe that's decades old and still flying, but it's not the same airplane it was when it was originally manufactured," Hansen said of the CF-18, Canada's longest-serving, multi-role fighter. "We've replaced so many aspects of the CF-18s in the inventory in Canada; they're really a completely different airplane than they were initially with respect to the radar, weapon systems, communication links, navigation equipment, Night Vision Goggles and Joint Helmet-Mounted Cuing System. These things are absolute game changers, and that's what makes them continue to be relevant today."

But there's a new kid on the block in the RCAF's arsenal, and you can't have a conversation about a modern NATO-aligned air force without talking about the F-35 Lightning II Joint Strike Fighter. With 1,000 F-35s produced, over 800 in service across the globe, Canada will receive the first of its 88 CF-35s in 2026 at Luke AFB, in the Unites States, in order to start training its aircrew. Though not privy to any of the F-35's classified RCAF operations, you better believe Jeremy Hansen's been paying attention to what's in the hangars at his old stomping grounds in between NASA meetings.

"It's hard for me to comment on the F-35 because I'm not read into the program, and I just don't need to know," Hansen said of the F-35 in RCAF service. "But just with unclassified conversations I've had with people, what stands out to me is the F-35 is an evolutionary leap in connectivity and networking. It's much more than just the airplane and what it physically can do; it's actually what it enables from the point of view of a network and sharing of information, providing a view of the battlespace and information for an intelligence network."

"There are all these cool aspects with a fifth-generation fighter that you just don't have available in the previous generation. I wish I knew more, but that's a very fascinating aspect of the F-35 program." An RCAF pilot of Jeremy's caliber will surely have a categoric knowledge of his country's most famous warbirds. But in 110-plus years of Canadian-powered flight, which was Canada's first lunar astronaut's all-time favorite? Is it the CF-100, Canuck, the only native-Canadian jet fighter produced in large numbers? His pride and joy CF-18? Or maybe the Avro CF-105 Arrow, widely believed to be the most capable jet interceptor in the world in the late 1950s before the project was abruptly halted.

Well, Jeremy Hansen's answer might surprise you. "I had the very extraordinary opportunity to fly the Canadair CL-13 Sabre. I took it to a few air shows and probably logged about 12 hours in it," Hansen said, reminiscing about his time at the stick of arguably the finest jet fighter of the very early Cold War, one which even the US Air Force employed at points during the conflict in Korea. "It was an extraordinary airplane. I was shocked by how well it flew and how dated the technology was. The leading edge slats move out and in with the airflow; I thought it was very elegant and a very easy airplane to fly. It also just looks the part of a jet fighter."

Hansen declined to pick a favorite Canadian fighter but noted that in his experience, people who've flown the full gambit of Canada's native jet fighters point to the CL-13 Sabre as the most remarkable. He also wrote a university paper about the CF-105 Arrow as a thinly veiled justification to learn more about the program. As Hansen pointed out, many of those scientists were recruited by NASA to work on the Apollo program.

So many of Artemis II's particulars remain up in the air at this juncture. But after spending half an hour talking with one of its astronauts, it's safe to say no faults lie in the selection of the crew whatsoever. It's also apt to say the mission's tentative success will be owed to its crew's keen problem-solving skills and in spite of anything that might go wrong.

Many thanks to Jeremy Hansen and the Canadian Space Agency's public relations team for giving us the time to sit down with the scientific equivalent of a rock star. From a certain point of view, no profession will ever be as effortlessly cool as being a literal astronaut. The next time we hear from Jeremy, there's a good chance the next destination is lunar orbit in short order.

But for all you hear about stories of Apollo and Space Shuttle astronauts not getting too emotional until they're strapped into their spacecraft mere minutes from launch, Hansen is doing everything in his power to take things in stride and enjoy the ride while it lasts. "I can relate to that sentiment, although I don't think I could necessarily answer whether it's going to be like that or not for me until I get all the way through it," Hansen said of his upcoming Artemis II launch, only ten or so months away at the time of this interview. "I do have these sorts of moments of realization along the way, and for me, there's been a lot of emotions associated with it, especially in the beginning, it was very humbling."

With Mission Commander Reid Weisman, Mission Specialist Christina Koch, and the Orion space capsule's Pilot, Victor Glover, alongside him, Artemis II's crew is due to bring the first person of color, the first woman, and the first non-American national to space for the first time in human history. As far as the non-American astronaut side of things goes, none of it would've been possible had it not been for a piece of international collaboration known as the Artemis Accords.

Signed by Canada in October 2020, this non-binding international agreement will soon permit astronauts from 33 signatories and counting from across Europe, Asia, Oceania, and the Americas to share in the spoils of a new-age space race quite unlike the original. But the Artemis Accords is not a free ride on NASA spacecraft to whichever countries align ideologically with the United States. In fact, the Artemis program and the Artemis Accords are two separate entities totally independent of one another.

Hansen and his crew will be distinguished guests aboard a slew of new spacecraft hardware benefiting from the latest advancements in aeronautical engineering, computing performance, and launch vehicle hardware. From the 322-foot (98.1-m) tall SLS launch vehicle with 8.8 million lbs of thrust at its disposal at liftoff to the ESA's European Service module, whose engine, battery cells, and life support systems form the heart and soul of the Artemis program, there's no shortage of astonishing technology at Hansen and company's disposal once they're up in space.

But to many, no other vehicle involved with Artemis II is more noteworthy than Lockheed Martin's Orion space capsule. With a striking silhouette reminiscent of an upsized Apollo Command Module, Orion is 50 percent more voluminous and can comfortably accommodate a fourth crew member as a result. As Orion demonstrated during its first trip around the Moon during the un-crewed Artemis I mission, NASA's priced space capsule's autopilot can do the job all on its own with ease.

But flight computers can never fully replace a human hand behind the stick when astronauts are allowed on board. With this in mind, intensely studying and becoming acclimated to Orion's intricate hardware is still just as vital as it was during the Apollo program. As Canada's first part-time resident of deep space can attest to, that's one heck of an intricate process. "We've been spending a lot of time learning everything about Orion," Hansen said of his duties while training at the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

More than 29,000 total hours of simulator time took place across 15 different NASA-run simulation facilities during the Apollo program. In time, Artemis II's crew will begin racking up hours in their own simulators. Through cutting-edge, real-time simulation of every feasible scenario at each point in the ten-day mission, each of the four crew will cram what once took a year or more of sim time into just under ten months. This means for Hansen and company, the grueling work ahead has a no-doubt historic end prize.

"I actually haven't done an integrated sim with Mission Control yet, I'm still sort of learning the vehicle. But in the new year, we'll be getting to that point where we'll be simulating aspects of the mission, putting in failures, having to overcome the failures while working with Mission Control. All of that is still evolving," Hansen said of the break-neck pace for Artemis II. With its launch date of September 2025, there's no time to lose. While the astronauts train up, so too will every other aspect of the mission, every space suit, every valve, computer, and every line of code, be developed in parallel.

"We're putting together a training flow that the next astronauts will follow, but we're sort of making that up as we go along. As things change, we'll just adapt our understanding," Hansen said of the relaxed yet undeniably thoughtful approach to Artemis II's mission development over the next year. "We sort of learn along with the developers, if you will." Of course, you'd hope Artemis II's crew would be doing plenty of scientific experiments while in transit to and in orbit around the Moon. The lunar dark side hasn't been observed by human eyes since Apollo 17 left the Moon's orbit back in 1973, after all.

With so little of Artemis' key infrastructure ready by the time the second mission launches, including the Gateway space station, a restriction on its ability to conduct science makes sense. But in Jeremy Hansen's own words, the strongest data points of the entire mission could be the crew themselves. "The biggest research facilities will be us, the four humans on board. So that will enable some really fascinating research opportunities. That will start a new dataset for human research in deep space. Speaking of the dark side of the Moon, because they wanted the near side lit, large portions of the dark side were typically dark during the Apollo program. Depending on when we launch, we may be able to see parts of the dark side of the Moon in a lighted condition that the Apollo astronauts never saw."

Under the right conditions, it's possible the astronauts on board could observe these portions of the lunar dark side in ways nothing other than a satellite has ever seen, let alone human eyes. "The geologists have explained to us that the human eye observation is very interesting to them. Apollo astronauts did have some observations that caught the eye that you don't necessarily pick up in a satellite observation, and they were very interested in what we might observe. We don't know if we will, but we definitely will be looking, and that's fun to think about."

With so many achievements and footnotes soon to pass in the leadup to Artemis II's launch, many questions about the intricate details still need to be answered. Or, at least, they'll be answered very soon. But Jeremy Hansen's previous career as a fighter jet jockey for the RCAF is just as fascinating as his work as an astronaut. As a veteran pilot of Canada's decades-long premiere twin-engine jet fighter, the CF-18 Hornet, Hansen is especially qualified to explain why this 40-year-old airframe continues to dominate Canadian airspace.

But there's a new kid on the block in the RCAF's arsenal, and you can't have a conversation about a modern NATO-aligned air force without talking about the F-35 Lightning II Joint Strike Fighter. With 1,000 F-35s produced, over 800 in service across the globe, Canada will receive the first of its 88 CF-35s in 2026 at Luke AFB, in the Unites States, in order to start training its aircrew. Though not privy to any of the F-35's classified RCAF operations, you better believe Jeremy Hansen's been paying attention to what's in the hangars at his old stomping grounds in between NASA meetings.

"It's hard for me to comment on the F-35 because I'm not read into the program, and I just don't need to know," Hansen said of the F-35 in RCAF service. "But just with unclassified conversations I've had with people, what stands out to me is the F-35 is an evolutionary leap in connectivity and networking. It's much more than just the airplane and what it physically can do; it's actually what it enables from the point of view of a network and sharing of information, providing a view of the battlespace and information for an intelligence network."

"There are all these cool aspects with a fifth-generation fighter that you just don't have available in the previous generation. I wish I knew more, but that's a very fascinating aspect of the F-35 program." An RCAF pilot of Jeremy's caliber will surely have a categoric knowledge of his country's most famous warbirds. But in 110-plus years of Canadian-powered flight, which was Canada's first lunar astronaut's all-time favorite? Is it the CF-100, Canuck, the only native-Canadian jet fighter produced in large numbers? His pride and joy CF-18? Or maybe the Avro CF-105 Arrow, widely believed to be the most capable jet interceptor in the world in the late 1950s before the project was abruptly halted.

Hansen declined to pick a favorite Canadian fighter but noted that in his experience, people who've flown the full gambit of Canada's native jet fighters point to the CL-13 Sabre as the most remarkable. He also wrote a university paper about the CF-105 Arrow as a thinly veiled justification to learn more about the program. As Hansen pointed out, many of those scientists were recruited by NASA to work on the Apollo program.

So many of Artemis II's particulars remain up in the air at this juncture. But after spending half an hour talking with one of its astronauts, it's safe to say no faults lie in the selection of the crew whatsoever. It's also apt to say the mission's tentative success will be owed to its crew's keen problem-solving skills and in spite of anything that might go wrong.

Many thanks to Jeremy Hansen and the Canadian Space Agency's public relations team for giving us the time to sit down with the scientific equivalent of a rock star. From a certain point of view, no profession will ever be as effortlessly cool as being a literal astronaut. The next time we hear from Jeremy, there's a good chance the next destination is lunar orbit in short order.