If you thought the era of re-useable space planes ended after Space Shuttle Atlantis touched down after STS-135, you've got another thing coming. Not only is the practice of designing spaceplanes alive and well, but an exciting second renaissance, a venerable post-Space Shuttle era of spaceplanes, is due to get underway any day now. When it does, Sierra Space's small but mighty Dream Chaser looks poised to get things started.

But don't be fooled. Dream Chaser isn't just the fruit of the ambitions of 21st-century engineers and scientists looking to reinvent the "wheel." Its origins are collected from a group of as many as seven different vehicle designs, some making it off the ground and others not. This is the story of the HL-20 Personnel Launch System, the long-defunct NASA spaceplane whose effort wasn't at all for nothing. In fact, it's pretty difficult to differentiate between Dream Chaser and the HL-20 on first impressions alone.

Only the HL-20's traditional front landing gear, compared to Dream Chaser's front landing skid, plus the different decal set and a less pronounced vertical stabilizer can tell the two apart unless you're already intimately familiar. From the blended lifting-body airframe to the shape of the cockpit and the overall diminutive size of both spaceplanes, it's hard not to tie the story of Dream Chaser to that of the HL-20. But to understand the impetus behind both spaceplanes, we need to remember the conditions in place at NASA during the late 1980s.

This period in NASA's history is one solidly within the Space Shuttle supremacy era at the agency. A time after former U.S. President Richard Nixon decreed the Shuttle was NASA's priority numero uno after the end of the Apollo program. It was a time when smaller annual budgets compared to the four-plus-percent or more of national GDP the agency took advantage of during the 60s necessitated a rapid shift towards un-crewed space probes in order to maintain any presence in deep space beyond low-Earth orbit.

In the earliest days of the Shuttle program, NASA envisioned a fleet of orbiters that could make trips into space as many as a hundred times or more per orbiter. A far cry away from the measly 135 missions flown across a fleet of six orbiters, we had to make do with reality. Studies conducted after the Shuttle's retirement in 2011 found that across all its launches, the average cost per launch of one Space Shuttle mission worked out to $1.6 billion per flight. It doesn't take a certified IRS teaching instructor to know cost figures like that weren't long-term sustainable.

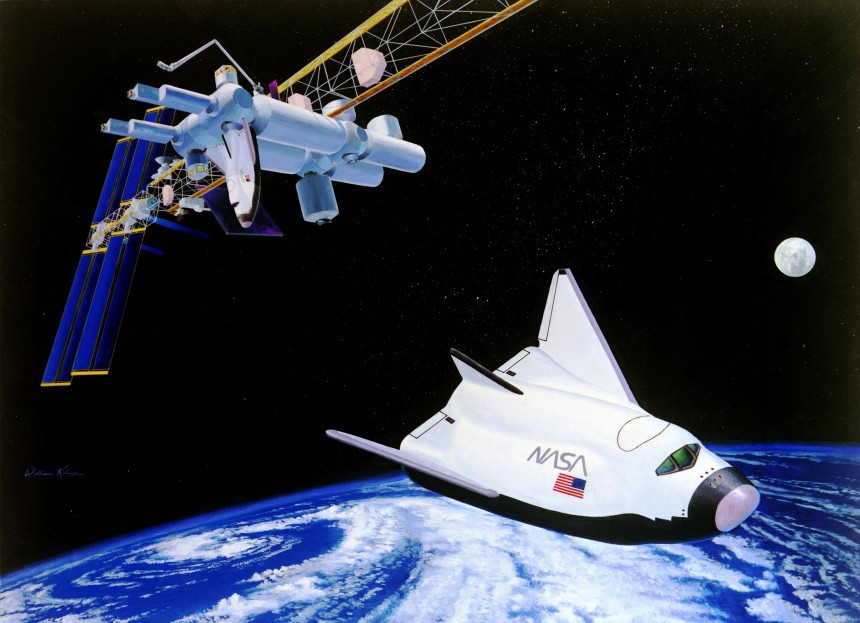

With this in mind, it makes sense why NASA and its associated aerospace contractors sought a smaller, less costly alternative to the Space Shuttle starting around the mid-to-late 1980s. At the same time these research initiatives were getting underway, NASA was beginning the blueprint phase for its second-generation national orbital space station, then dubbed Space Station Freedom. Safe to say, the prospects of a cost-effective, small vehicle capable of bringing astronauts and a paltry sum of cargo up to low-Earth orbit with a minimum of fuss was something tantalizing to a space agency perpetually at odds with the accounting department.

However, the question of where NASA engineers could draw inspiration for their new spacecraft still permeated the program. Ultimately, this spark came not from the Space Shuttle directly but from some of the prototype aircraft and spacecraft designed beforehand. Particularly, specialized lifting body aircraft whose entire fuselage and undercarriage provide the bulk of the lift in flight were of particular interest to NASA for use in a miniature space plane, a program initially dubbed the Personnel Launch System (PLS) program.

Novel airplanes like Northrop's M2-F2, M2-F3, and HL-10, as well as Martin Marietta's X-24A and X-24B, proved to be vital in the development of NASA's next-gen mini-shuttle. But perhaps no other vehicle, built or otherwise, played a more integral role in what ultimately became the HL-20 than the Boeing X-20 Dyna-Soar of the late 1960s. Though it canceled itself just as construction was getting underway, the Dyna-Soar introduced a spaceplane form factor vital not just to the HL-20 but to Dream Chaser as well.

I.e., a small, compact space plane capable of being launched atop a medium-lift launch vehicle like a Titan III, rendevous with other man-made objects in low Earth before re-entering the atmosphere and landing like an airplane back on the surface. Even the Soviets had the same idea in the form of the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-105, which was later developed into the un-crewed Bor-4 atmospheric test vehicle. Rivaled only to the Dyna-Soar in terms of its importance to the HL-20 program; it's said that NASA engineers were heavily inspired by the photographs of the Bor-4 when the time came to finalize the blueprints for the new spacecraft.

At NASA's Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, work began on bringing together all of HL-20's inspirations into a single mockup prototype, which, hopefully, would be ferrying American astronauts into low-Earth orbit by the time the 21st century came around. In 1990, the Langley Research Center employed engineering students at North Carolina A&T University as well as North Carolina State University to construct a one-to-one scale mockup of the HL-20 to present to the press and the awaiting public.

With dimensions of 8.84 meters (29.002 ft) long and a wingspan of 7.16 meters (23.5 ft) with the wing tips fully extended, the HL-20 could've fit comfortably inside the payload bay of a Space Shuttle orbiter with room to spare, assuming the wing tips were retracted. At nine meters (30 ft) long with a 7.01-meter (23-ft) wingspan fully extended, Dream Chaser's dimensions are within inches of that of the HL-20. As for the type of launch vehicle that could have been employed in the HL-20 program, it's hard to say definitively.

Even in the years before SpaceX and the great private space vehicle revolution, a litany of medium-to-heavy-lift booster rockets like the Delta II, Ariane 4, Atlas V, and even the legacy Titan III series could have realistically done the job. Plans called for a spaceplane capable of a litany of different missions from space station rendevous to low-Earth orbit satellite servicings and even deploying fleets of microsatellites from inside the HL-20's paltry payload compartment. As a machine that could fill the gaps should the Space Shuttle program find itself compromised (which it later would after the loss of Orbiter Columbia), the HL-20 stood alone.

At least, it would have had the project ever made it past the mockup phase. Sadly, NASA never gave the green light on the project, despite attempts by private aerospace firms like Rockwell International and Lockheed Skunk Works to introduce further layers of feasibility to the project. Even a radical proposal to scale up the HL-20 spacecraft by 42 percent, creating the HL-42 concept, was rejected by NASA without funding. In most cases, that would have been a wrap for project HL-20.

Instead, the design entered a profound period of limbo where its design became the inspiration for future space projects with no real concrete plans for execution in place. That was until 2004. That year, a Southern California-based upstart firm called SpaceDev commenced development on a project called Dream Chaser. With the basic design for the HL-20 in hand, SpaceDev, flanked with help by Lockheed Martin, Aerojet, and the University of Colorado at Boulder, among others, attempted to complete what the HL-20 had started.

With a bare minimum of modifications over the base design, including the front landing skid mentioned above, SpaceDev took the HL-20 formula and made it even more practical. So when the time came for the massive Sierra Nevada Corporation to buy out SpaceDev in late 2008, the company already had a capable set of spaceplane blueprints at its disposal. Today, the Dream Chaser, now under the control of SNC's legally separate offshoot corporation Sierra Space, anticipates Dream Chaser will conduct its first test launch in April 2024 aboard the equally brand-new Vulcan Centaur rocket from United Launch Alliance.

Safe to say, when Dream Chaser makes its first trip to space, it'll have the benefit of roughly 30 years of R&D behind its back when it's all said and done. If you ask us, it'll be one of the most feel-good, cathartic moments in the history of modern spaceflight. Oh, what we'd give to be at the launch pad the day that happens.

Only the HL-20's traditional front landing gear, compared to Dream Chaser's front landing skid, plus the different decal set and a less pronounced vertical stabilizer can tell the two apart unless you're already intimately familiar. From the blended lifting-body airframe to the shape of the cockpit and the overall diminutive size of both spaceplanes, it's hard not to tie the story of Dream Chaser to that of the HL-20. But to understand the impetus behind both spaceplanes, we need to remember the conditions in place at NASA during the late 1980s.

This period in NASA's history is one solidly within the Space Shuttle supremacy era at the agency. A time after former U.S. President Richard Nixon decreed the Shuttle was NASA's priority numero uno after the end of the Apollo program. It was a time when smaller annual budgets compared to the four-plus-percent or more of national GDP the agency took advantage of during the 60s necessitated a rapid shift towards un-crewed space probes in order to maintain any presence in deep space beyond low-Earth orbit.

In the earliest days of the Shuttle program, NASA envisioned a fleet of orbiters that could make trips into space as many as a hundred times or more per orbiter. A far cry away from the measly 135 missions flown across a fleet of six orbiters, we had to make do with reality. Studies conducted after the Shuttle's retirement in 2011 found that across all its launches, the average cost per launch of one Space Shuttle mission worked out to $1.6 billion per flight. It doesn't take a certified IRS teaching instructor to know cost figures like that weren't long-term sustainable.

However, the question of where NASA engineers could draw inspiration for their new spacecraft still permeated the program. Ultimately, this spark came not from the Space Shuttle directly but from some of the prototype aircraft and spacecraft designed beforehand. Particularly, specialized lifting body aircraft whose entire fuselage and undercarriage provide the bulk of the lift in flight were of particular interest to NASA for use in a miniature space plane, a program initially dubbed the Personnel Launch System (PLS) program.

Novel airplanes like Northrop's M2-F2, M2-F3, and HL-10, as well as Martin Marietta's X-24A and X-24B, proved to be vital in the development of NASA's next-gen mini-shuttle. But perhaps no other vehicle, built or otherwise, played a more integral role in what ultimately became the HL-20 than the Boeing X-20 Dyna-Soar of the late 1960s. Though it canceled itself just as construction was getting underway, the Dyna-Soar introduced a spaceplane form factor vital not just to the HL-20 but to Dream Chaser as well.

I.e., a small, compact space plane capable of being launched atop a medium-lift launch vehicle like a Titan III, rendevous with other man-made objects in low Earth before re-entering the atmosphere and landing like an airplane back on the surface. Even the Soviets had the same idea in the form of the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-105, which was later developed into the un-crewed Bor-4 atmospheric test vehicle. Rivaled only to the Dyna-Soar in terms of its importance to the HL-20 program; it's said that NASA engineers were heavily inspired by the photographs of the Bor-4 when the time came to finalize the blueprints for the new spacecraft.

With dimensions of 8.84 meters (29.002 ft) long and a wingspan of 7.16 meters (23.5 ft) with the wing tips fully extended, the HL-20 could've fit comfortably inside the payload bay of a Space Shuttle orbiter with room to spare, assuming the wing tips were retracted. At nine meters (30 ft) long with a 7.01-meter (23-ft) wingspan fully extended, Dream Chaser's dimensions are within inches of that of the HL-20. As for the type of launch vehicle that could have been employed in the HL-20 program, it's hard to say definitively.

Even in the years before SpaceX and the great private space vehicle revolution, a litany of medium-to-heavy-lift booster rockets like the Delta II, Ariane 4, Atlas V, and even the legacy Titan III series could have realistically done the job. Plans called for a spaceplane capable of a litany of different missions from space station rendevous to low-Earth orbit satellite servicings and even deploying fleets of microsatellites from inside the HL-20's paltry payload compartment. As a machine that could fill the gaps should the Space Shuttle program find itself compromised (which it later would after the loss of Orbiter Columbia), the HL-20 stood alone.

At least, it would have had the project ever made it past the mockup phase. Sadly, NASA never gave the green light on the project, despite attempts by private aerospace firms like Rockwell International and Lockheed Skunk Works to introduce further layers of feasibility to the project. Even a radical proposal to scale up the HL-20 spacecraft by 42 percent, creating the HL-42 concept, was rejected by NASA without funding. In most cases, that would have been a wrap for project HL-20.

With a bare minimum of modifications over the base design, including the front landing skid mentioned above, SpaceDev took the HL-20 formula and made it even more practical. So when the time came for the massive Sierra Nevada Corporation to buy out SpaceDev in late 2008, the company already had a capable set of spaceplane blueprints at its disposal. Today, the Dream Chaser, now under the control of SNC's legally separate offshoot corporation Sierra Space, anticipates Dream Chaser will conduct its first test launch in April 2024 aboard the equally brand-new Vulcan Centaur rocket from United Launch Alliance.

Safe to say, when Dream Chaser makes its first trip to space, it'll have the benefit of roughly 30 years of R&D behind its back when it's all said and done. If you ask us, it'll be one of the most feel-good, cathartic moments in the history of modern spaceflight. Oh, what we'd give to be at the launch pad the day that happens.