If you follow the news around space travel these days, you'll be liable to be inundated up to your eyeballs with claims that NASA's SLS rocket, the heart, and soul behind the Artemis program, is an overpriced, unaffordable albatross that could be put to better use building something else. Never mind that these kinds of arguments have been thrown around since the Apollo days. But rest assured, NASA's new Moon rocket could've been an even bigger mess had they not radically changed course.

This is the story of NASA's Ares-class super-heavy lift vehicle. Before SLS, before Artemis, and before the Artemis Accords that promised to bring dozens of countries to the Moon and beyond, this was the booster rocket slated to bring humanity back beyond low-Earth orbit. Safe to say, things never went smoothly, hence why we're talking about it in hindsight right now. But to understand the impetus behind the Ares rocket, we need to understand what being a NASA rocket engineer was like in the days post-Apollo.

You'd be astonished at the downright ambitious human-crewed space missions planned in the Apollo program's immediate aftermath. Plans established by American aerospace contractors and a consortium of NASA scientists and engineers led by Wernher Von Braun called for a nuclear-powered, crewed mission to Mars, which could've landed as soon as the early 1980s had NASA's Apollo budget stayed at the funding levels it received in the mid-to-late 1960s. But, as space fans 50 years later still can't get over, the Nixon administration's plans for NASA after Apollo 17 had almost nothing to do with human-crewed space exploration whatsoever.

With the exception of the Space Shuttle program, another historically expensive space initiative, NASA's presence in deep space was restricted to un-crewed probes for the rest of the 20th century and into the 21st. The rationale behind why the only U.S. President ever to resign seemingly nuked NASA's deep space initiatives on his way out the door is up for debate. Some claim that a wave of anti-NASA sentiment from working-class urban Americans was the primary culprit. A small but very vocal minority of folks claimed American tax money was better off feeding the needy was a better use of government funding.

Others claim that it was President Nixon himself who declared there was no point in funding a space program with an enthusiast base who was more likely than not to vote Democrat in the next election anyway. Regardless, what resulted was a period where no human being has left the confines of low-Earth orbit since the early 1970s. A few design proposals did pass across NASA's desk in that time, most notably the Comet HHLV of the early 1990s, which used a great deal of Apollo hardware like the core stage of the Saturn V rocket.

Of course, Comet HHLV never got off the ground. It wouldn't be until 2004 that a genuine, good-faith effort to put humans back on the Moon finally took shape in the form of the Constellation program. Signed into law by then-President George W. Bush, Constellation took the basic ideas formulated by Apollo and attempted to modify them to fit 21st-century sensibilities. Unlike Apollo, where one massive booster rocket carried crew and cargo beyond LEO, Constellation aimed to employ two bespoke boosters, one for the crew and one for the payload, to forge humankind's first lunar colony.

Like the Comet HHLV, Constellation's launch vehicles were due to employ a breadth of hardware developed for previous NASA initiatives, in this case, the Space Shuttle. From the Shuttle's iconic orange main fuel tank to its Aerojet-Rocketdyne main engines and its unmistakable solid rocket boosters, NASA's plan to repurpose old Shuttle tech should have theoretically saved billions in R&D costs throughout Constellation's service life. With the program's Altair lunar lander and Lockheed Martin Orion command module in tow, NASA figured if all went to plan, they could land humans on the Moon by the end of the 2010s.

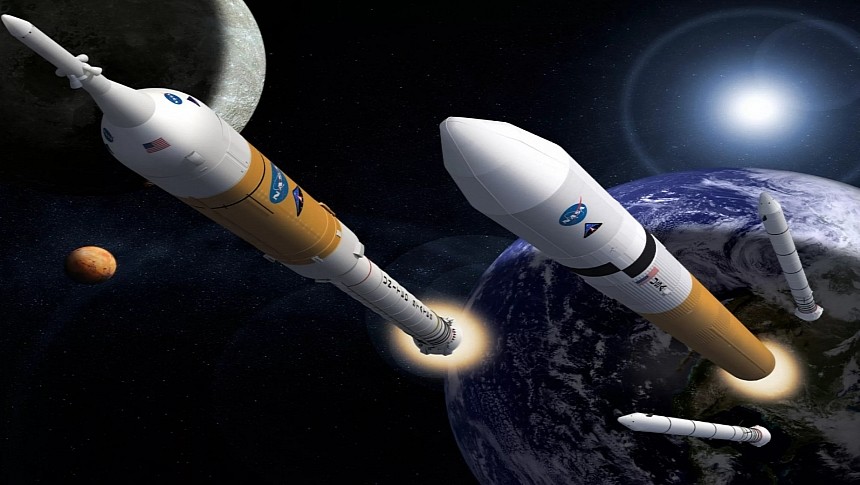

Yeah, that didn't wind up happening. But you can't argue the renderings and blueprints weren't impressive. The two booster rockets designed for Constellation, Ares I, and Ares V, did at least have the horsepower on paper to bring these lunar ambitions to fruition. With dimensions of 94 meters (308 ft) tall and five-and-a-half meters (18 ft) in diameter, the Ares I human-crewed launch vehicle was a proverbial pencil-neck of a machine. One that looked demonstrably like a scaled-up solid-rocket booster, mostly because its first stage was indeed a reworked Space Shuttle SRB with an added five solid-fuel segments over the standard four to account for the weight of the Orion capsule.

Its second stage, a single Aerojet-Rocketdyne J-2X liquid-fueled rocket engine, was selected to help the Orion capsule break the Earth's gravity and make it to orbit. With 294,000 lbs of thrust at its disposal (1,307 kN), Ares I was designed to be far more capable than its needle-thin silhouette might indicate. While Ares I handled human-crewed ascent to orbit, the larger Ares V cargo lifter handled the real heavy lifting. Even from just looking at renderings of what NASA's Cargo Launch Vehicle (CaLV), later named the Ares V, would have looked like, it's impossible not to draw parallels to the super-heavy launch vehicle NASA ultimately produced, the SLS.

With a slated height of between 358 and 381 feet (109-116m), depending on the payload fairing, Ares V would have been far and away the largest launch vehicle ever constructed. Even in comparison to the SLS Block I at 322 feet (98 m) tall, Ares V would have been unlike nothing else ever launched in terms of height, assuming the vehicle launched on its original schedule years ahead of SpaceX's Starship. Between its two beefier five-stage SRBs from the Virginia-based Alliant Techsystems and five Aerojet-Rocketdyne RS-25 engines borrowed from the Space Shuttle, Ares V had the theoretical grunt of no machine real or conceptual in the mid-to-late 2000s.

We're talking a bare minimum of 7.3 million lbs (31,115.09 kN) of thrust at launch. Sure, it's not as impressive as the 8.8 million lbs (39,000 kN) of thrust the SLS pushed out during Artemis I, but it was still head and shoulders above anything flying in the 2000s, real or theoretical. More excitingly, Aerojet Rocketdyne even developed an all-new, liquid-fueled rocket engine specifically for the purpose of providing a more cost-effective means of launching NASA heavy launch vehicles in the form of the RS-68.

Admittedly, the RS-68 origins began as an alternate engine for the Delta IV launch vehicle. But when the Ares program came knocking, the pairing was a match made in heaven to NASA. With as much as 80 percent fewer moving parts than the multi-use RS-25s, the RS-68B model designed just for the Ares V took an almost top fuel dragster-like approach to putting cargo into space. I.e., go balls to the wall for one glorious launch before a complete rebuild or even being full-on scrapped. Had Ares V flown with four RS-68Bs, it stood a chance of surpassing the thrust figures generated even by the SLS.

Combined with 3.4 million lbs (15,000 kN) of thrust produced by the Ares I's first stage and 294,000 lbs (1,308 kN) made by its second stage, project Constellation seemed slated to have world-class rocket horsepower at its back. Add in a promising design for a lunar module successor in the form of the Altair lander and a genuinely workable command capsule from Lockheed Martin in Orion, and it looked like everything was in place to proceed with the first flight of the Ares I rocket under the Ares I-X mission, and from there, to the Moon.

On October 28th, 2009, with a dummy fifth stage and a mock payload, the first launch of Ares I went off without a hitch from launch pad 39B at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Pad Abort tests related to the Orion capsule proceeded with this successful flight in May of the following year. Even so, powerful oscillation and vibrations during both flights were found to have likely shaken the crew of an Orion capsule like a paint can. In a long enough time span, these issues could have been worked out. But the U.S. Government had other plans.

Just as plans were being finalized to test fly Ares V by 2018 and land Americans on the Moon by the end of the decade, a single stroke of U.S. President Barack Obama's pen brought everything crashing down. It's said that an internal NASA research group, the Review of the United States Human Space Flight Plans Committee's findings released in October 2009 damned the Ares program as too cost ineffective, citing the adoption of two separate launch platforms in a single program as one of the key contributing factors.

Just like that, Lockheed Martin's Orion capsule was the only piece of Constellation hardware that survived the death of the Constellation program and made it into the subsequent Artemis program founded in 2017. Even so, NASA's critics still bemoan Artemis' SLS rocket as an overpriced albatross. Little do they know, things could have been even worse. So please appreciate SLS for what it is, and remember that spaceflight runs more on stacks of Ben Franklins than it does LOX and H2.

You'd be astonished at the downright ambitious human-crewed space missions planned in the Apollo program's immediate aftermath. Plans established by American aerospace contractors and a consortium of NASA scientists and engineers led by Wernher Von Braun called for a nuclear-powered, crewed mission to Mars, which could've landed as soon as the early 1980s had NASA's Apollo budget stayed at the funding levels it received in the mid-to-late 1960s. But, as space fans 50 years later still can't get over, the Nixon administration's plans for NASA after Apollo 17 had almost nothing to do with human-crewed space exploration whatsoever.

With the exception of the Space Shuttle program, another historically expensive space initiative, NASA's presence in deep space was restricted to un-crewed probes for the rest of the 20th century and into the 21st. The rationale behind why the only U.S. President ever to resign seemingly nuked NASA's deep space initiatives on his way out the door is up for debate. Some claim that a wave of anti-NASA sentiment from working-class urban Americans was the primary culprit. A small but very vocal minority of folks claimed American tax money was better off feeding the needy was a better use of government funding.

Others claim that it was President Nixon himself who declared there was no point in funding a space program with an enthusiast base who was more likely than not to vote Democrat in the next election anyway. Regardless, what resulted was a period where no human being has left the confines of low-Earth orbit since the early 1970s. A few design proposals did pass across NASA's desk in that time, most notably the Comet HHLV of the early 1990s, which used a great deal of Apollo hardware like the core stage of the Saturn V rocket.

Like the Comet HHLV, Constellation's launch vehicles were due to employ a breadth of hardware developed for previous NASA initiatives, in this case, the Space Shuttle. From the Shuttle's iconic orange main fuel tank to its Aerojet-Rocketdyne main engines and its unmistakable solid rocket boosters, NASA's plan to repurpose old Shuttle tech should have theoretically saved billions in R&D costs throughout Constellation's service life. With the program's Altair lunar lander and Lockheed Martin Orion command module in tow, NASA figured if all went to plan, they could land humans on the Moon by the end of the 2010s.

Yeah, that didn't wind up happening. But you can't argue the renderings and blueprints weren't impressive. The two booster rockets designed for Constellation, Ares I, and Ares V, did at least have the horsepower on paper to bring these lunar ambitions to fruition. With dimensions of 94 meters (308 ft) tall and five-and-a-half meters (18 ft) in diameter, the Ares I human-crewed launch vehicle was a proverbial pencil-neck of a machine. One that looked demonstrably like a scaled-up solid-rocket booster, mostly because its first stage was indeed a reworked Space Shuttle SRB with an added five solid-fuel segments over the standard four to account for the weight of the Orion capsule.

Its second stage, a single Aerojet-Rocketdyne J-2X liquid-fueled rocket engine, was selected to help the Orion capsule break the Earth's gravity and make it to orbit. With 294,000 lbs of thrust at its disposal (1,307 kN), Ares I was designed to be far more capable than its needle-thin silhouette might indicate. While Ares I handled human-crewed ascent to orbit, the larger Ares V cargo lifter handled the real heavy lifting. Even from just looking at renderings of what NASA's Cargo Launch Vehicle (CaLV), later named the Ares V, would have looked like, it's impossible not to draw parallels to the super-heavy launch vehicle NASA ultimately produced, the SLS.

We're talking a bare minimum of 7.3 million lbs (31,115.09 kN) of thrust at launch. Sure, it's not as impressive as the 8.8 million lbs (39,000 kN) of thrust the SLS pushed out during Artemis I, but it was still head and shoulders above anything flying in the 2000s, real or theoretical. More excitingly, Aerojet Rocketdyne even developed an all-new, liquid-fueled rocket engine specifically for the purpose of providing a more cost-effective means of launching NASA heavy launch vehicles in the form of the RS-68.

Admittedly, the RS-68 origins began as an alternate engine for the Delta IV launch vehicle. But when the Ares program came knocking, the pairing was a match made in heaven to NASA. With as much as 80 percent fewer moving parts than the multi-use RS-25s, the RS-68B model designed just for the Ares V took an almost top fuel dragster-like approach to putting cargo into space. I.e., go balls to the wall for one glorious launch before a complete rebuild or even being full-on scrapped. Had Ares V flown with four RS-68Bs, it stood a chance of surpassing the thrust figures generated even by the SLS.

Combined with 3.4 million lbs (15,000 kN) of thrust produced by the Ares I's first stage and 294,000 lbs (1,308 kN) made by its second stage, project Constellation seemed slated to have world-class rocket horsepower at its back. Add in a promising design for a lunar module successor in the form of the Altair lander and a genuinely workable command capsule from Lockheed Martin in Orion, and it looked like everything was in place to proceed with the first flight of the Ares I rocket under the Ares I-X mission, and from there, to the Moon.

Just as plans were being finalized to test fly Ares V by 2018 and land Americans on the Moon by the end of the decade, a single stroke of U.S. President Barack Obama's pen brought everything crashing down. It's said that an internal NASA research group, the Review of the United States Human Space Flight Plans Committee's findings released in October 2009 damned the Ares program as too cost ineffective, citing the adoption of two separate launch platforms in a single program as one of the key contributing factors.

Just like that, Lockheed Martin's Orion capsule was the only piece of Constellation hardware that survived the death of the Constellation program and made it into the subsequent Artemis program founded in 2017. Even so, NASA's critics still bemoan Artemis' SLS rocket as an overpriced albatross. Little do they know, things could have been even worse. So please appreciate SLS for what it is, and remember that spaceflight runs more on stacks of Ben Franklins than it does LOX and H2.