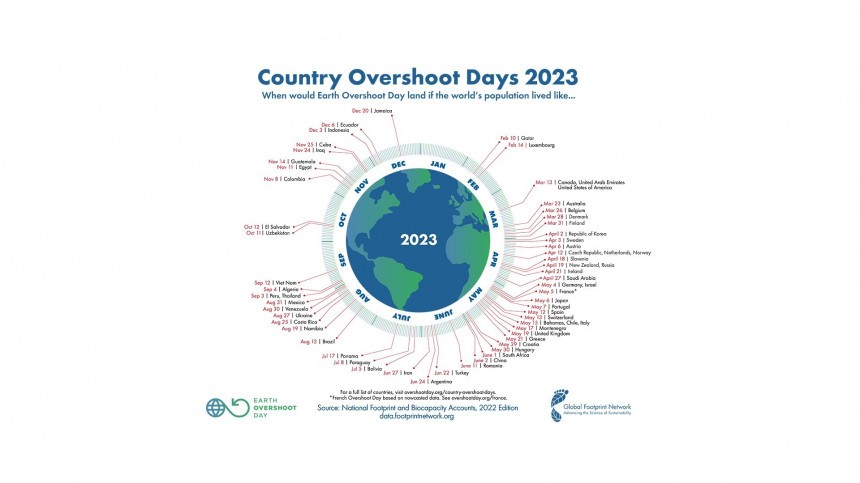

This year's Earth Overshoot Day fell on August 2. Since 2011, it has been happening in the early days of this month, which may give the impression that things have been more or less stable in the past 12 years. However, when you think about what the date means, the only relief would be that it arrived consistently later. How can we exhaust all the planet's natural resources in a given year by August? Circular economy principles could help us avoid that, but they would also break the legs of the traditional industry, especially the automotive.

Stellantis recently took part in the Motor & Equipment Manufacturers Association (MEMA) Sustainability Summit in Troy, Michigan. The company presented its efforts in circular economy with the SUSTAINera brand, which provides remanufactured parts for older cars. According to the carmaker, these goods "provide savings of up to 80% of raw materials and 50% of non-emitted CO2 as compared to their equivalent new parts." Stellantis also said that "remanufacturing in North America makes up 72% of the Circular Economy business, with recycling and repair accounting for 28%." Although this is a valid effort, it is far from enough.

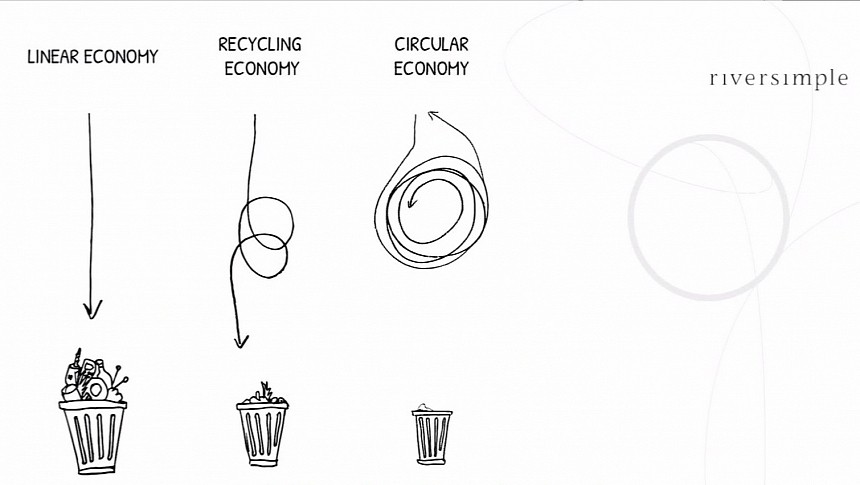

Classic cartoons made in the 1950s explained to children how things were supposed to work: it would start with someone willing to sell new products. The more they sold, the more money this entrepreneur would have to expand the business. Eventually, these goods would be exported, opening new markets for that company. Some cartoons would also talk about the capital market and how selling shares could help make the company bigger. This is called the linear economy model for a good reason: companies take (raw materials), make (their products), and sell them for people to use and eventually discard them. The final destination for these products is disposal (and the pollution that this process creates).

Circular economy preaches that products should last longer, which immediately undermines an incentive on which automakers have relied for most of their careers: new designs and the urge that people have to buy the latest product available. Planned obsolescence would have to end for vehicles to last as much as possible. In other words, we would not have new cars every six years or midcycle refreshes. Buying a new or used vehicle would depend on rational motives because they would be very similar.

What defines the idea as circular is that these cars should be locally refurbished or recycled when they break down. What would be the benefit of transporting waste for recycling? The closer a given product is to the place that can put it to work again or transform it into new things, the less carbon emissions will be involved in the whole thing. Those principles would be a massive issue for the model currently followed by the automotive industry and the idea of exporting vehicles.

Mass production started with Henry Ford in the US, from where the vehicles were first exported on a large scale worldwide. If a given market had enough demand, a local plant would be established there. Europe liked the idea, which was also followed by Japan, South Korea, and, more recently, China. Other countries also export, but not thanks to local companies: foreign automakers produce there and send these products abroad. Exporting is a safeguard for when the internal market is not going well. This is one of the reasons for carmakers to unify their lineups and try to sell the same products everywhere.

Just like factories, American junkyards followed the country's lead and soon spread all over the world. They would probably not exist with a circular economy: the recycling work they perform would be more thorough, turning them into something other than a deposit for old and depleted car bodies. All good parts would be immediately separated and stored somewhere. Those components or body parts without economic value or in a condition that did not allow them to be reused would be sent to recycling companies.

Now imagine any of our major current automakers producing cars only for their local markets. If they wanted to sell vehicles in other countries, they would have to build factories there, which would also be in charge of recycling cars that could not be remanufactured. Exporting as many cars as possible would not be a goal or a relief in a circular economy. How would shipped vehicles be locally available for recycling? That would mean the raw materials to make new cars or refurbish existing ones would not be available. On the other hand, it would also help avoid the risks of transporting vehicles in roll-on/roll-off (RoRo) cargo ships, as the Fremantle Highway recently exposed.

To be frank, the local demand would be quickly fulfilled, which also poses another challenge to the current industrial model: selling goods cannot be the only way to make a profit. Riversimple already addressed that by refusing to sell its cars: it will offer mobility services. In other words, customers will pay to use the vehicles. Everything from hydrogen fueling to insurance will be included in the monthly fee. Would any other car company follow the same idea? At this point and after what Stellantis shared, that's very unlikely. Most automakers want changes that help keep everything as it is.

The enthusiasm people used to feel for cars is vanishing at a fast pace. Some activists even think we would be better off without them. However, most people still like the freedom of getting behind the steering wheel and going wherever they want or need to go. Circular economy principles allow us to keep that without contributing to Earth Overshoot Day as much as the current model does. Although this shift is inevitable, we are left wondering when industries will realize that and who will take the lead. From what we have seen so far, disruption will not come from traditional players, which is a real pity: they will go down trying to defend the way they do things until they can't do them anymore.

Classic cartoons made in the 1950s explained to children how things were supposed to work: it would start with someone willing to sell new products. The more they sold, the more money this entrepreneur would have to expand the business. Eventually, these goods would be exported, opening new markets for that company. Some cartoons would also talk about the capital market and how selling shares could help make the company bigger. This is called the linear economy model for a good reason: companies take (raw materials), make (their products), and sell them for people to use and eventually discard them. The final destination for these products is disposal (and the pollution that this process creates).

Circular economy preaches that products should last longer, which immediately undermines an incentive on which automakers have relied for most of their careers: new designs and the urge that people have to buy the latest product available. Planned obsolescence would have to end for vehicles to last as much as possible. In other words, we would not have new cars every six years or midcycle refreshes. Buying a new or used vehicle would depend on rational motives because they would be very similar.

Mass production started with Henry Ford in the US, from where the vehicles were first exported on a large scale worldwide. If a given market had enough demand, a local plant would be established there. Europe liked the idea, which was also followed by Japan, South Korea, and, more recently, China. Other countries also export, but not thanks to local companies: foreign automakers produce there and send these products abroad. Exporting is a safeguard for when the internal market is not going well. This is one of the reasons for carmakers to unify their lineups and try to sell the same products everywhere.

Just like factories, American junkyards followed the country's lead and soon spread all over the world. They would probably not exist with a circular economy: the recycling work they perform would be more thorough, turning them into something other than a deposit for old and depleted car bodies. All good parts would be immediately separated and stored somewhere. Those components or body parts without economic value or in a condition that did not allow them to be reused would be sent to recycling companies.

To be frank, the local demand would be quickly fulfilled, which also poses another challenge to the current industrial model: selling goods cannot be the only way to make a profit. Riversimple already addressed that by refusing to sell its cars: it will offer mobility services. In other words, customers will pay to use the vehicles. Everything from hydrogen fueling to insurance will be included in the monthly fee. Would any other car company follow the same idea? At this point and after what Stellantis shared, that's very unlikely. Most automakers want changes that help keep everything as it is.

The enthusiasm people used to feel for cars is vanishing at a fast pace. Some activists even think we would be better off without them. However, most people still like the freedom of getting behind the steering wheel and going wherever they want or need to go. Circular economy principles allow us to keep that without contributing to Earth Overshoot Day as much as the current model does. Although this shift is inevitable, we are left wondering when industries will realize that and who will take the lead. From what we have seen so far, disruption will not come from traditional players, which is a real pity: they will go down trying to defend the way they do things until they can't do them anymore.