This history of the Canadian aerospace sector can best be described as a series of proverbial kicks to the nads by countries more powerful than itself. Never mind that the AEA Silver Dart, the first heavier-than-air flying machine to be built largely by Canadians, made the Wright Flyer look like a balsa wood toy. At so many opportunities, ground-breaking Canadian aircraft were cursed to fumble at the CFL-regulation goal line while airplanes from other nations hogged the spotlight.

Want proof positive? Well, the story of Avro Canada C102 Jetliner, to use another sports reference, must have hurt like the 28-3 incident. If you know, you know. Had events gone even slightly different, it would be Canada, not the US or Great Britain, claiming the title of first to bring a turbojet airliner to commercial service. But in a global aviation sector that feels cursed sometimes, the program went all wrong seemingly as soon as the first prototype was finished. But before all of that, at the end of the Second World War, a triumphant Canada was eager to show its fellow victorious allies that they had a place at the post-war aviation table.

Like the United States, Canada's wartime infrastructure remained virtually undamaged by the horrors of the largest war in human history. As hundreds of thousands of Canadian soldiers made their way home from Europe or the Pacific, many became vital cogs in Canada's post-war industrial renaissance. During this time, Canadian engineers and scientists often found themselves poached by American aerospace firms to assist in their Cold War tech race with the Soviet Union. But even more stayed behind, preventing a national brain drain by forming an aerospace sector that mimicked that of the U.S. and Europe.

Among the groups that took advantage of this wealth of aeronautical know-how was Trans-Canada Air Lines (TCA). As Canada's ostensible flag carrier airline since before World War II, TCA was eager to keep pace with international airlines from Great Britain and the United States by offering new and exciting aircraft in a post-war commercial aviation dead-set on innovating like it's going out of style. By war's end, both the Allied and Axis nations had developed novel gas-turbine jet engines far more powerful and capable than piston engines.

More or less aware of turbojet aircraft projects originating in Great Britain, Germany, and the U.S., TAC desired these powerful engines to power the next generation of Canadian airliners. By year's end of 1945, TCA's engineering superintendent, Jim Bain, had already blueprinted a single-aisle, quad-engine airliner that, if all went to plan, would be the first designed from the ground up to run on jet power to enter commercial service. At first, plans called to use four newly minted Armstrong Siddeley Mamba turboprop engines. But proceedings changed in a hurry when Bain and a few TCA colleagues visited Rolls-Royce's aerospace R&D center in England.

At this meeting, Bain met with the head of Rolls-Royce's aero engine division, Ernest Hives. Hives was able to convince his Canadian guests to ditch the Mamba turboprops in favor of the company's under-development AJ65 axial-flow turbojets instead. Ultimately, the AJ65 project became the Rolls-Royce Avon. On April 9th, 1946, TCA and Rolls-Royce finalized plans for a 36-seat jet airliner with a top speed no slower than 425 mph (684 km/h), a range of at least 1,200 m (1,900 km), and a maximum possible single flight of 500 m (800 km) when accounting for loiter times over airports.

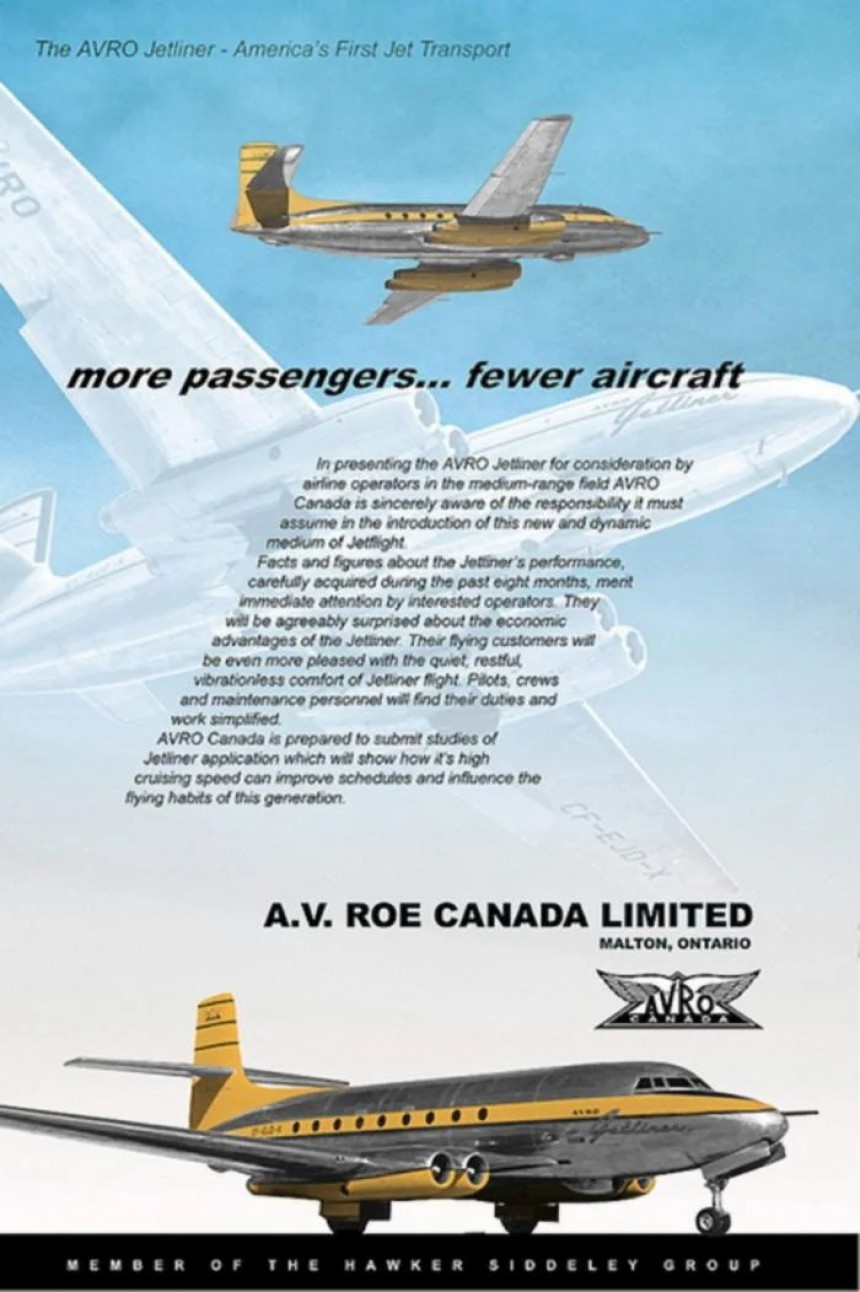

The only question left was who would manufacture this new jet to TCA's specifications. The answer came in the form of A.V. Roe and Company, more commonly known as Avro. Founded out of a former cotton spinning mill in Manchester and headquartered 45 minutes north in Lancashire, it was Avro who, after World War II, acquired former Victory Aircraft firm's production facility in Malton, 35 minutes northwest of Toronto, Ontario. During the war, the facility operated as a shadow factory, building British Avro Lancaster bombers and Hawker Hurricane fighters safely hidden from the German Luftwaffe on North American soil.

By now a fully-owned subsidiary of Hawker-Siddeley, what became Avro Canada made a few more design changes once the plans were in place to build the first Canadian jet airliner in Malton, Ontario. For starters, questions of whether the Rolls-Royce Avon engines would be flight-certified in time to get the jet in the air before the 40s were out prompted an audible in the engine department. Gone were the not-yet-ready Avons; in their place were four Rolls-Royce Dervents famous for their use in the Gloster Meteor, the first Allied jet fighter to enter service during World War II.

The Derwent would power the Meteor fighter from the F.3 variant first flown on September 11th, 1944. Though it was considerably less powerful than the Avon, a four-engine configuration did at least allow for a greater degree of control in the event of a single-engine failure. Certain factions within both Avro Canada and Trans-Canada Air Lines were left rather salty by these proceedings but soon conceded on the above-mentioned grounds that four Derwents were ultimately better than zero Avons.

With dimensions of 82 feet, five inches (25.12 m) long with a 28-foot, one-inch (29.9 m) wingspan, Avro Canada's new jet, soon dubbed the C102 Jetliner, was sized more like a regional puddle jumper than Boeing's leviathan 707 and 747, the aircraft most often associated with quad-jet airliners. Ever-cognizant of British and American aerospace juggernauts like Boeing and de Havilland racing to build the first operational jet airliner, Avro Canada engineers raced against time not just to meet their own deadlines but to beat their allies into the air.

Taxi testing began in 1949 on what was to be the sole C102 Jetliner completed. Problems with its landing gear tires and anti-skid braking system during high-speed taxi tests delayed the Jetliner's first flight. Much to the chagrin of TCA, knowing full well that the British especially were dangerously close to fielding their own jet airliner. Finally, on August 10th, 1949, the C102 coaxed itself into the air for its first test flight. So then, time for champagne and a victory dance, right. Well, no, not quite.

Only 13 days earlier, the prototype de Havilland DH.106 Comet 1 made its maiden flight on July 27th, 1949, out of the Hatfield Aerodrome in Hertfordshire with company test pilot John "Cats Eyes" Cunningham at the controls. By a time span of less than two weeks, the British had sniped the title of the world's first purpose-built jet airliner by the engineering equivalent of a photo finish. To add injury to insult instead of vice-versa, the C102's second flight, six days later on August 16th, nearly ended in complete disaster when its landing gear failed to deploy on final approach.

But with the pride of a nation still behind, the Jetliner proceeded to make its best impression of a hockey puck, gliding across the runway as if on a freshly Zamboni'd rink before coming to a stop with only minor damage. Repairs were completed, and the Jetliner was back flying less than a month later. In April of the following year, the Jetliner hauled a load of mail, the first to be transported from Canada by turbojet power. Its route from Toronto to New York City was reached in just 58 minutes or almost half the previous record by a piston-engined aircraft. Legend has it that ground crews in New York were spooked by the shockingly loud engines, unlike anything they'd heard before.

On paper, at least, it looked like Avro Canada had delivered Trans-Canada Air Line's request with flying colors. Full-scale production was due to begin sometime in the early 1950s, with full-scale commercial service achievable by the middle of the decade. But as potential customers watched Avro Canada struggle to bring the nation's first jet fighter, the CF-101 Canuck, forces within the Royal Canadian Air Force strongly urged Avro Canada to focus whole-heartedly on the CF-101.

The C102 was used as a chase plane in the CF-101 program until 1956, but no production orders ever arrived, and the second prototype was never completed. The Jetliner had its flightworthy status revoked, and its airframe was offered up by Avro Canada to the Canadian National Research Council in the nation's capital of Ottawa, Ontario.

Before its grounding, the eccentric billionaire aviator Howard Hughes tried to arrange for the Jetliner program to be restarted and even sat behind the its flight stick on a few occasions. Still, these bids never materialized anything. Due to a lack of long-term storage at the museum, only the nose section was spared from the scrap yard. Today, the sole Avro Canada Jetliner's remains are on display at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum's Reserve Hangar in Ottawa, where it's remained since being donated in 1967. There, it serves as a somber reminder of what might have been.

Had it not been for the controversial and polarizing demise of the CF-105 Arrow that same decade, the C102 Jetliner would have easily been the greatest missed opportunity in the history of aviation in Canada. For this reason, it makes sense why the considerable advancements made by Avro Canada routinely get left out of the conversation around the Cold War aviation boom. It's why we commend those men and women today, right here, right now.

Check back soon for more vintage aviation profiles here on autoevolution.

Like the United States, Canada's wartime infrastructure remained virtually undamaged by the horrors of the largest war in human history. As hundreds of thousands of Canadian soldiers made their way home from Europe or the Pacific, many became vital cogs in Canada's post-war industrial renaissance. During this time, Canadian engineers and scientists often found themselves poached by American aerospace firms to assist in their Cold War tech race with the Soviet Union. But even more stayed behind, preventing a national brain drain by forming an aerospace sector that mimicked that of the U.S. and Europe.

Among the groups that took advantage of this wealth of aeronautical know-how was Trans-Canada Air Lines (TCA). As Canada's ostensible flag carrier airline since before World War II, TCA was eager to keep pace with international airlines from Great Britain and the United States by offering new and exciting aircraft in a post-war commercial aviation dead-set on innovating like it's going out of style. By war's end, both the Allied and Axis nations had developed novel gas-turbine jet engines far more powerful and capable than piston engines.

More or less aware of turbojet aircraft projects originating in Great Britain, Germany, and the U.S., TAC desired these powerful engines to power the next generation of Canadian airliners. By year's end of 1945, TCA's engineering superintendent, Jim Bain, had already blueprinted a single-aisle, quad-engine airliner that, if all went to plan, would be the first designed from the ground up to run on jet power to enter commercial service. At first, plans called to use four newly minted Armstrong Siddeley Mamba turboprop engines. But proceedings changed in a hurry when Bain and a few TCA colleagues visited Rolls-Royce's aerospace R&D center in England.

The only question left was who would manufacture this new jet to TCA's specifications. The answer came in the form of A.V. Roe and Company, more commonly known as Avro. Founded out of a former cotton spinning mill in Manchester and headquartered 45 minutes north in Lancashire, it was Avro who, after World War II, acquired former Victory Aircraft firm's production facility in Malton, 35 minutes northwest of Toronto, Ontario. During the war, the facility operated as a shadow factory, building British Avro Lancaster bombers and Hawker Hurricane fighters safely hidden from the German Luftwaffe on North American soil.

By now a fully-owned subsidiary of Hawker-Siddeley, what became Avro Canada made a few more design changes once the plans were in place to build the first Canadian jet airliner in Malton, Ontario. For starters, questions of whether the Rolls-Royce Avon engines would be flight-certified in time to get the jet in the air before the 40s were out prompted an audible in the engine department. Gone were the not-yet-ready Avons; in their place were four Rolls-Royce Dervents famous for their use in the Gloster Meteor, the first Allied jet fighter to enter service during World War II.

The Derwent would power the Meteor fighter from the F.3 variant first flown on September 11th, 1944. Though it was considerably less powerful than the Avon, a four-engine configuration did at least allow for a greater degree of control in the event of a single-engine failure. Certain factions within both Avro Canada and Trans-Canada Air Lines were left rather salty by these proceedings but soon conceded on the above-mentioned grounds that four Derwents were ultimately better than zero Avons.

Taxi testing began in 1949 on what was to be the sole C102 Jetliner completed. Problems with its landing gear tires and anti-skid braking system during high-speed taxi tests delayed the Jetliner's first flight. Much to the chagrin of TCA, knowing full well that the British especially were dangerously close to fielding their own jet airliner. Finally, on August 10th, 1949, the C102 coaxed itself into the air for its first test flight. So then, time for champagne and a victory dance, right. Well, no, not quite.

Only 13 days earlier, the prototype de Havilland DH.106 Comet 1 made its maiden flight on July 27th, 1949, out of the Hatfield Aerodrome in Hertfordshire with company test pilot John "Cats Eyes" Cunningham at the controls. By a time span of less than two weeks, the British had sniped the title of the world's first purpose-built jet airliner by the engineering equivalent of a photo finish. To add injury to insult instead of vice-versa, the C102's second flight, six days later on August 16th, nearly ended in complete disaster when its landing gear failed to deploy on final approach.

But with the pride of a nation still behind, the Jetliner proceeded to make its best impression of a hockey puck, gliding across the runway as if on a freshly Zamboni'd rink before coming to a stop with only minor damage. Repairs were completed, and the Jetliner was back flying less than a month later. In April of the following year, the Jetliner hauled a load of mail, the first to be transported from Canada by turbojet power. Its route from Toronto to New York City was reached in just 58 minutes or almost half the previous record by a piston-engined aircraft. Legend has it that ground crews in New York were spooked by the shockingly loud engines, unlike anything they'd heard before.

The C102 was used as a chase plane in the CF-101 program until 1956, but no production orders ever arrived, and the second prototype was never completed. The Jetliner had its flightworthy status revoked, and its airframe was offered up by Avro Canada to the Canadian National Research Council in the nation's capital of Ottawa, Ontario.

Before its grounding, the eccentric billionaire aviator Howard Hughes tried to arrange for the Jetliner program to be restarted and even sat behind the its flight stick on a few occasions. Still, these bids never materialized anything. Due to a lack of long-term storage at the museum, only the nose section was spared from the scrap yard. Today, the sole Avro Canada Jetliner's remains are on display at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum's Reserve Hangar in Ottawa, where it's remained since being donated in 1967. There, it serves as a somber reminder of what might have been.

Had it not been for the controversial and polarizing demise of the CF-105 Arrow that same decade, the C102 Jetliner would have easily been the greatest missed opportunity in the history of aviation in Canada. For this reason, it makes sense why the considerable advancements made by Avro Canada routinely get left out of the conversation around the Cold War aviation boom. It's why we commend those men and women today, right here, right now.