Space stations, big metal tubes in low-Earth orbit pressurized to roughly the same atmospheric pressure you'd find on sea level so a bunch of squishy, fragile meat sacks can conduct science experiments and learn to live in an environment our Lord almighty never fathomed we'd wind up making inhabiting. We might take the modern International Space Station for granted after 30 years in orbit, but it would have never been possible without its lesser-known, less celebrated ancestor, Skylab.

On the 50th anniversary of Skylab's historic launch aboard the same Saturn V rocket that put human beings on the Moon, let's take a deep dive into what made America's first occupied orbital workshop the gold standard for human-crewed space stations for the next decade and a half. It's a story that foundations in the existing Apollo program but didn't quite get off the ground until its dog days. But even before Apollo, as early as the 1950s, rocket engineers like Wernher Von Braun and sci-fi writers like Arthur C. Clarke were already envisioning space stations as a vital part of mankind's transition to a space-fairing species.

Ideas of a massive, ring-shaped orbital space station with enough centrifugal force to within to generate artificial gravity may have sounded great on paper, but in an era where NASA accounted for a staggering four percent of the U.S. Government's GDP during the 1960s due to the Apollo program, all these designs accomplished was inspiring some awesome sci-fi movies. Ever marvel at the massive, rotating leviathan Space Station V from 2001: A Space Odyssey? The one with the Pan-Am SSTO shuttle that docks to a station that sports a Howard Johnson Hotel and picturephone booths that might as well have inspired Apple's Facetime?

The design for Station V might as well have come right off the drawing board of von Braun himself. The reality of the situation when it comes to space stations is radically different. Just look at the Soviet Salyut station; that predates Skylab by just a couple of years. Launched in April 1971, the combined Salyut orbital laboratories and secret Almaz military space stations were as close to tin cans in space as was possible in the early 1970s. At just 66 feet (20 m) wide and 13 feet (4 m) across, the only thing preventing this cramped three-person spacecraft from being called a Coke can in Low Earth Orbit was a Soviet embargo on Coca-Cola products.

Interestingly, the three-man Soyuz 11 crew, the first to occupy a Saylut station, became the first humans to die in the vacuum of space when their capsule de-pressurized on their return journey to Earth. So then, so long as a similar catastrophic event of this nature didn't transpire with Skylab, the U.S. seemed to be in a position to overtake the Soviets in orbital laboratory technology in the early-to-mid-1970s. Enter the McDonnell Douglas Corporation, who, just five weeks after Apollo 11's successful lunar landing in August 1969, inked a contract with NASA to take two Saturn V third-stage boosters, gut them of all their internals, and create the world's most advanced orbital workshop.

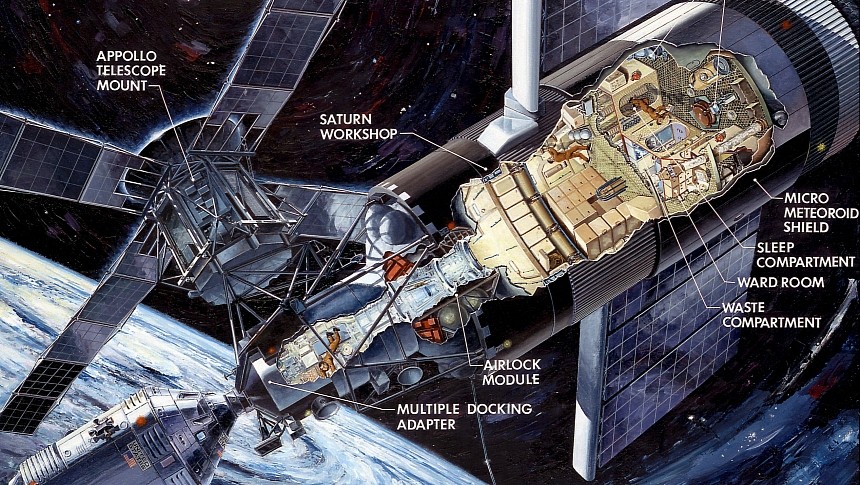

Dubbed Skylab in February 1970, a full-sized mockup was completed even before the final three Apollo missions, 18, 19, and 20, were canceled by Congress. Over time, the Skylab concept vehicle evolved to sport four distinct major components, the Airlock Module, the Multiple Docking Adapter, the Apollo Telescope Mount, and the heart and soul of the whole operation, the Orbital Workshop. Together, these components accounted for what was, at the time, the largest spacecraft ever conceived by a significant margin.

At 170,000 lbs fully-loaded, Skylab weighed more than a fully loaded Boeing 757-200 without accounting for the weight of the space station's crew. Over the course of almost half a decade, McDonnell Douglass painstakingly designed and assembled the Skylab Orbital Workshop at their facility in Huntington Beach, California, an hour south of Los Angeles, before it was delivered to the Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida, on the morning of Sept. 23, 1972. Over the next eight months, NASA engineers inside the colossal Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) attached the Skylab station to the top of the very last operational Saturn V rocket.

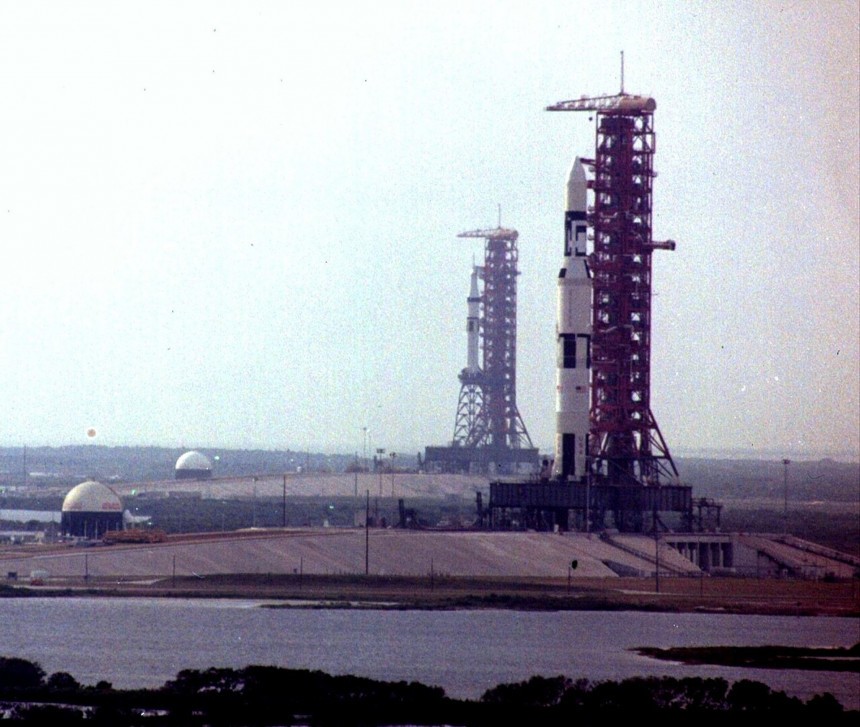

It wasn't until April of the following year that the whole leviathan of a machine, rocket, and space station included, was transported via NASA's iconic treaded rocket crawler to KSC's Launch Pad 39A, the very same pad where Apollo 11 had lifted off just a few years earlier. The launch process for what was dubbed Skylab 1 seemed simple enough on paper but endlessly complicated in practice. While Skylab's Saturn V launch vehicle sat at LC-39A, the neighboring pad, LC-39B, was mounted with a smaller Saturn IB rocket carrying the lab's awaiting crew.

While the larger craft launched and situated itself comfortably above the Karman Line at an apogee altitude of around 274 miles (441 km) above the Earth's surface. But no sooner did Skylab's Saturn V rise from its launch pad on May 14, 1973, did problems begin to emerge. Only seconds after one minute into the flight, NASA mission control observed the Skylabs micrometeoroid shield deploying well ahead of schedule. With the aerodynamic forces at play, the exposed instrument folded like a red-hot chocolate bar. Furthermore, not all of Skylab's external solar arrays deployed successfully as Saturn V completed the station's transit to low-Earth orbit.

Combine this unpleasantness with an impinged retrorocket ripping away a portion of one solar panel, and NASA had quite a conundrum on its hands, one that necessitated an abort on Skylab's first crewed launch. A further ten days of Mission Control troubleshooting and underwater training for Skylab's crew were needed to even attempt to save Skylab station. By this point, America's first space station had cost the U.S. taxpayers upwards of $2.2 billion, or around $15 billion in modern money. Safe to say, failure was not an option once again.

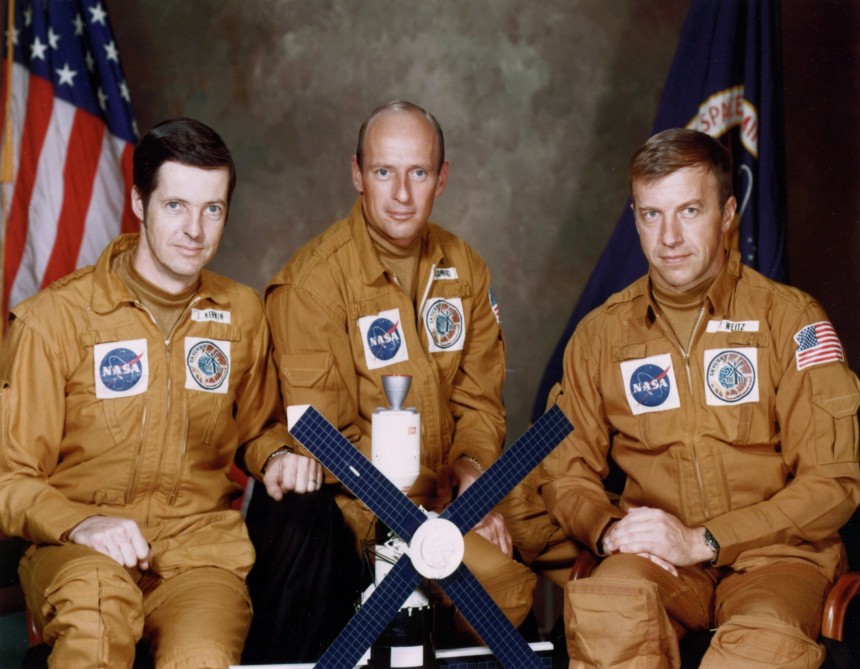

In spite of everything, Skylab II launched with a North American Command Module and Service module in tow aboard the above-mentioned Saturn IB rocket, iconic milk-stool umbilical support tower, and all on May 25, 1973. Upon rendevous with the stricken Skylab, Commander and Naval Officer Charles "Pete" Conrad, Science Pilot and Medical Doctor Joseph Kerwin, and CSM Pilot and fellow Naval Officer. Once that was complete, the main task became restoring the vessel's interior to human-appropriate temperatures.

But once again, there was another snag. Nine straight hard docking maneuvers all failed. Wearing modified variants of the Apollo program's Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU), the three-person crew needed to disassemble the complex Skylab docking unit in order to gain entry to the airlock, then the Orbital Laboratory and Apollo Telescope Mount. Finally, after gaining entry to Skylab, NASA engineer Jack "Mr. Fix It" Kinzler devised an idea to turn a collapsable parasail stored in the Command Module into an impromptu sun shield.

At long last, Skylab was in business, still not at full power, but in good enough health to begin the primary mission, studying the effects of zero-gravity on the human body over a long-term basis. Over the next two human-crewed Skylab missions, III and IV, a total of 172 days were spent with human occupation aboard the orbital station and conducted experiments pertaining to everything from solar storm cycles, Earth-bound geology, and human biology, among other areas.

Though it was hoped the then in-development Space Shuttle could have boosted the station to maintain its orbit, it sadly couldn't be fielded in time. And so, Skylab de-orbited harmlessly on July 11th, 1979, scattering a debris field across the Indian Ocean and Western Oceania. To this day, the United States has not fielded its own LEO space station since Skylab, opting instead to be the lynchpin nation in the world's most intricate and expensive machine currently in orbit, the International Space Station.

Ideas of a massive, ring-shaped orbital space station with enough centrifugal force to within to generate artificial gravity may have sounded great on paper, but in an era where NASA accounted for a staggering four percent of the U.S. Government's GDP during the 1960s due to the Apollo program, all these designs accomplished was inspiring some awesome sci-fi movies. Ever marvel at the massive, rotating leviathan Space Station V from 2001: A Space Odyssey? The one with the Pan-Am SSTO shuttle that docks to a station that sports a Howard Johnson Hotel and picturephone booths that might as well have inspired Apple's Facetime?

The design for Station V might as well have come right off the drawing board of von Braun himself. The reality of the situation when it comes to space stations is radically different. Just look at the Soviet Salyut station; that predates Skylab by just a couple of years. Launched in April 1971, the combined Salyut orbital laboratories and secret Almaz military space stations were as close to tin cans in space as was possible in the early 1970s. At just 66 feet (20 m) wide and 13 feet (4 m) across, the only thing preventing this cramped three-person spacecraft from being called a Coke can in Low Earth Orbit was a Soviet embargo on Coca-Cola products.

Interestingly, the three-man Soyuz 11 crew, the first to occupy a Saylut station, became the first humans to die in the vacuum of space when their capsule de-pressurized on their return journey to Earth. So then, so long as a similar catastrophic event of this nature didn't transpire with Skylab, the U.S. seemed to be in a position to overtake the Soviets in orbital laboratory technology in the early-to-mid-1970s. Enter the McDonnell Douglas Corporation, who, just five weeks after Apollo 11's successful lunar landing in August 1969, inked a contract with NASA to take two Saturn V third-stage boosters, gut them of all their internals, and create the world's most advanced orbital workshop.

At 170,000 lbs fully-loaded, Skylab weighed more than a fully loaded Boeing 757-200 without accounting for the weight of the space station's crew. Over the course of almost half a decade, McDonnell Douglass painstakingly designed and assembled the Skylab Orbital Workshop at their facility in Huntington Beach, California, an hour south of Los Angeles, before it was delivered to the Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida, on the morning of Sept. 23, 1972. Over the next eight months, NASA engineers inside the colossal Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) attached the Skylab station to the top of the very last operational Saturn V rocket.

It wasn't until April of the following year that the whole leviathan of a machine, rocket, and space station included, was transported via NASA's iconic treaded rocket crawler to KSC's Launch Pad 39A, the very same pad where Apollo 11 had lifted off just a few years earlier. The launch process for what was dubbed Skylab 1 seemed simple enough on paper but endlessly complicated in practice. While Skylab's Saturn V launch vehicle sat at LC-39A, the neighboring pad, LC-39B, was mounted with a smaller Saturn IB rocket carrying the lab's awaiting crew.

While the larger craft launched and situated itself comfortably above the Karman Line at an apogee altitude of around 274 miles (441 km) above the Earth's surface. But no sooner did Skylab's Saturn V rise from its launch pad on May 14, 1973, did problems begin to emerge. Only seconds after one minute into the flight, NASA mission control observed the Skylabs micrometeoroid shield deploying well ahead of schedule. With the aerodynamic forces at play, the exposed instrument folded like a red-hot chocolate bar. Furthermore, not all of Skylab's external solar arrays deployed successfully as Saturn V completed the station's transit to low-Earth orbit.

In spite of everything, Skylab II launched with a North American Command Module and Service module in tow aboard the above-mentioned Saturn IB rocket, iconic milk-stool umbilical support tower, and all on May 25, 1973. Upon rendevous with the stricken Skylab, Commander and Naval Officer Charles "Pete" Conrad, Science Pilot and Medical Doctor Joseph Kerwin, and CSM Pilot and fellow Naval Officer. Once that was complete, the main task became restoring the vessel's interior to human-appropriate temperatures.

But once again, there was another snag. Nine straight hard docking maneuvers all failed. Wearing modified variants of the Apollo program's Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU), the three-person crew needed to disassemble the complex Skylab docking unit in order to gain entry to the airlock, then the Orbital Laboratory and Apollo Telescope Mount. Finally, after gaining entry to Skylab, NASA engineer Jack "Mr. Fix It" Kinzler devised an idea to turn a collapsable parasail stored in the Command Module into an impromptu sun shield.

At long last, Skylab was in business, still not at full power, but in good enough health to begin the primary mission, studying the effects of zero-gravity on the human body over a long-term basis. Over the next two human-crewed Skylab missions, III and IV, a total of 172 days were spent with human occupation aboard the orbital station and conducted experiments pertaining to everything from solar storm cycles, Earth-bound geology, and human biology, among other areas.