The United States Air Force is the largest, most powerful aerial fighting force in the history of warfare. What's the second largest? That'd be the U.S. Navy. But like two brothers fighting for their father's attention after he legitimately comes home from buying milk and cigarettes, the bickering between the Air Force and Navy for sweet Pentagon money defined much of the Cold War. There are a few reasons for this animosity. But to some minds, one stands alone in terms of significance.

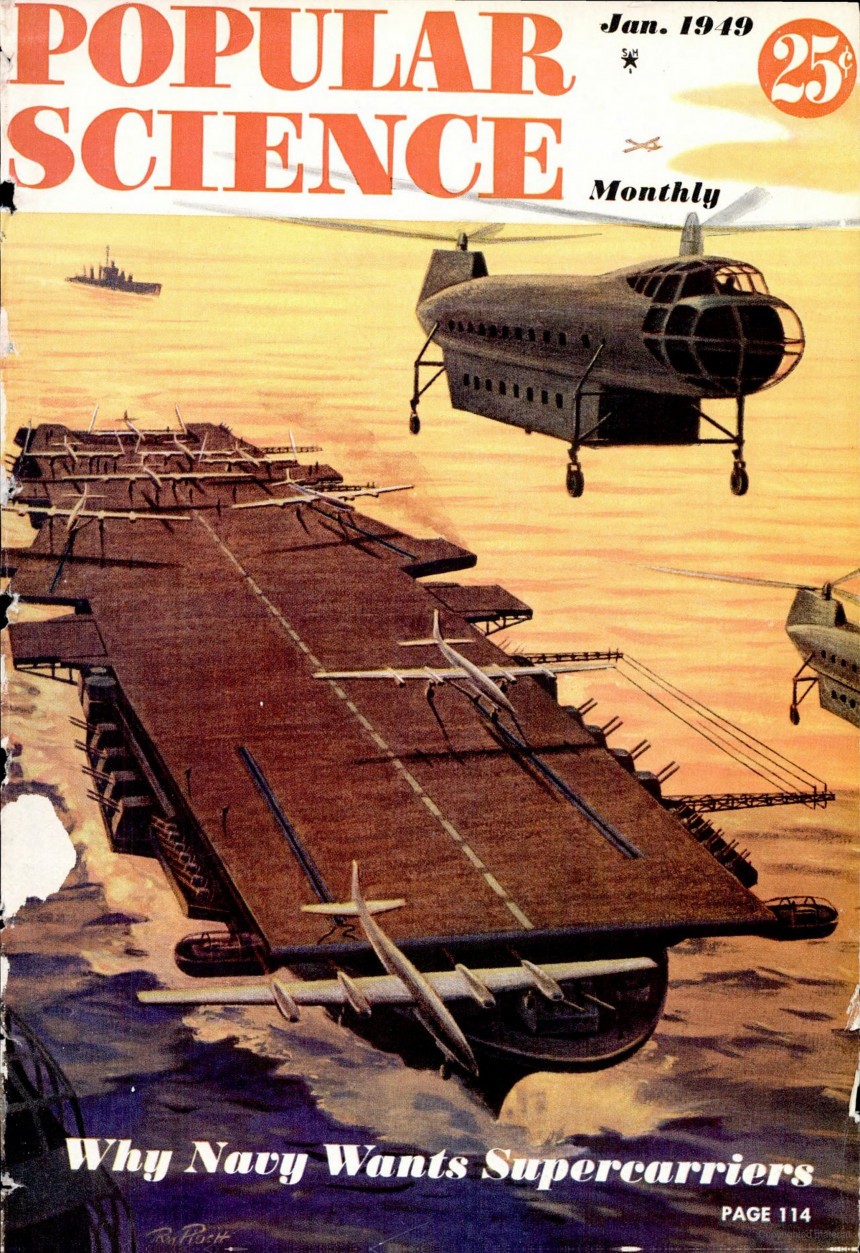

What would said program be, exactly? What one military asset could so make or break for either side of the Air Force/Navy dynamic that it starts a catfight between them, potentially endangering national security in the process? Well, a colossal Navy aircraft carrier so large it can launch nuclear-capable strategic bombers and new-fangled jet fighters from its decks certainly fits the picture. This is the saga of the USS United States, a supercarrier so controversial that the Navy and Air Force beefed about it for decades.

Let us paint the scene for you. It's the mid-1940s. Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan lie in ruins, along with most of Central and Eastern Europe and a decent part of East Asia. Emerging from the smoke relatively unscathed was the United States Military, now the pre-eminent power in global geopolitics. In the immediate aftermath of the war, the pecking order for all of the U.S. Military's branches was largely set in stone. The Army had domain over the nation's ground forces, tanks, infantry, and so on, not handled by the Marine Corps. It also held total dominion over its land-based aircraft through the Army Air Corps.

Meanwhile, the US Navy, with battleships, destroyers, subs, aircraft carriers, and all, controlled the airspace along any maritime route its ships may travel. Yes, the Coast Guard and Marines were there as well. But it was clear which two branches wore the pants in the years following President Harry S. Truman's first proper administration. Or, at least, it was this way for a couple of years after the war.

With the National Security Act of 1947 signed in September of that year, the Army Air Corps re-organized formally into the US Air Force, and boy-howdy, did they have plans ready to royally tick off the Navy. The cornerstone of the Air Force's nuclear doctrine in the very early Cold War was long-range, land-based strategic bombers, which, at least in the Air Force's mind at the time, were essentially impervious to enemy fighters and could pierce enemy airspace with impunity before dropping nukes and flying home.

This worked quite well during World War II, as the Allied daylight bombing campaign attested to. But in a paradigm that'd come to define U.S. defense budgets for decades, if the Air Force had shiny, nuclear-armed toys, the Navy wanted them too. Chief among the belly-achers from the Navy was Admiral Marc Mitscher, a veteran of both World Wars who commanded the lauded Fast Carrier Task Force during the Battle of Iwo Jima, as well as seeing service during the Battle of Midway, Leyte Gulf, Okinawa, and even the Doolittle Raid.

What Mitchser desired for the Navy was an aircraft carrier capable of launching nuclear-armed strategic jet bombers off its decks to attack military installations of the Soviet Union or its allies. Interestingly enough, for the atomic age, Navy top brass wished to keep the nukes attached to bombers instead of powering the ship itself, as they called for the proposed carrier to run on traditional boilers and steam turbines and have a range of around 12,000 nautical miles with a crew of 4,000 people. Further requests called for a flush-deck carrier deck design without an island center to allow for storing nuclear bombers with huge wingspans on deck.

Flush-deck carriers often require an auxiliary command ship to conduct the operations usually found on a carrier's command structure. These duties included radar warning detection to alert the supercarrier of incoming attacks. As a result, had it ever been built, the ship would've likely been unable to operate outside a Navy carrier strike group. Typically, these groups consist of at least one aircraft carrier flanked by a consortium of cruisers, destroyers, frigates, support ships, and the occasional group of submarines.

So to say, a lone wolf nation-crusher like modern US Navy carriers can be, this proposed ship was not. Even so, the Navy's strong desire to match the Air Force in nuclear bombing capability blinded them from blatant flaws in the design of their tentative new supercarrier. Dubbed the USS United States (CVA-58), and named for one of the first frigates built by the infant Congress back in 1794, the vessel was designed from the ground up to be a flagship for the entirety of the US Navy and named accordingly. With proposed dimensions of 1,090 feet (330 m) long with a 125-foot (38-m) beam at the waterline, the United States would've displaced as much as 83,200 tons when laden with crew, aircraft, and support vehicles.

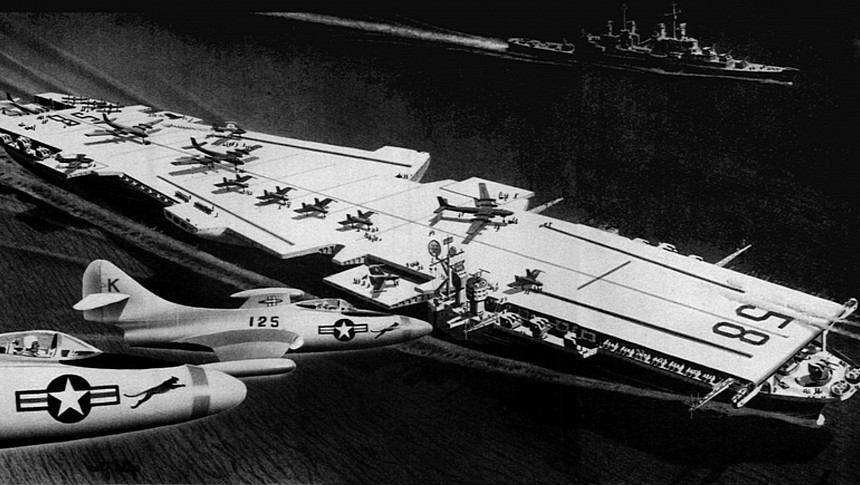

For some context, a modern American supercarrier like the USS Gerald R. Ford displaces around 100,000 tons, is fully loaded, and has been deployed as recently as 2022. For a carrier design from the late 1940s to nearly reach parity with modern ships in terms of displacement is nothing short of astonishing. As for what kind of aircraft would sail aboard CVA-58, artistic drawings depict a range of Navy jets. This includes the Grumman F9F Panther, the McDonnell FH-1 Phantom, and the Vaught F7U Cutlass, on top of un-named models of future Navy heavy bombers that would've been tailor-made to serve aboard the United States class supercarrier.

Some reports even say the Douglas A3D Skywarrior was also slated for service aboard CVA-58. For defensive armament, a full battery of eight five-inch canons, 16 76-mm autocannons, and up to 20 smaller 20 mm Oerlikon anti-aircraft cannons for the small chance enemy aircraft are able to pierce CVA-58's airspace. In short, the ship would've been tough for the Soviets or any other fighting force to sink. Admiral Mitchser never lived to see his prized ship take place, as he died suddenly while on assignment in 1947. But as design work continued, it was decided that one American shipyard was the only facility fit for the job.

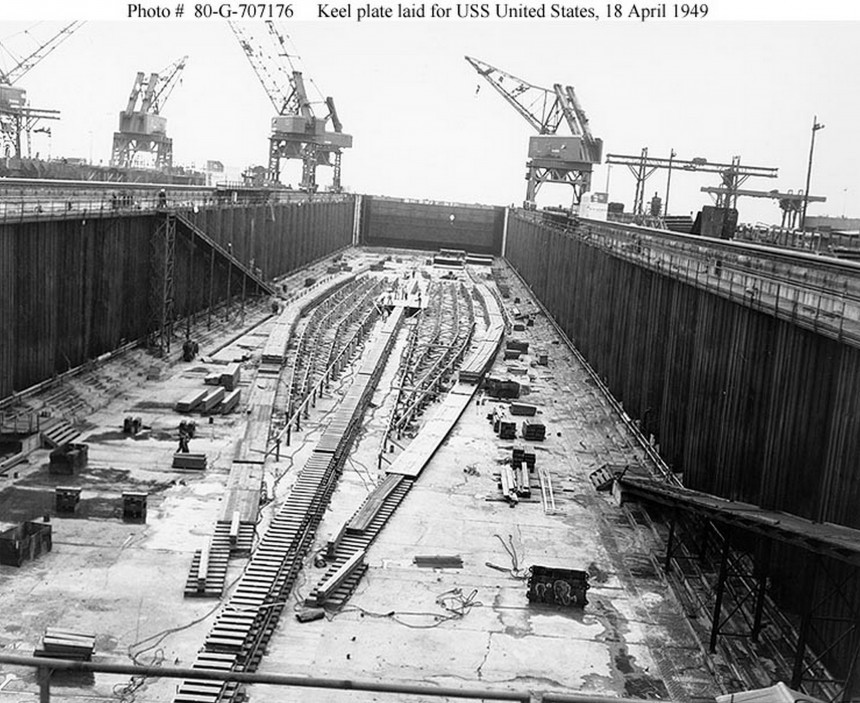

The yard in question was the famous Newport News Shipbuilding firm of Newport News, Virginia. The yard's been one of North America's premiere warship manufacturers since the late 1890s and was one of the only shipyards in the Western Hemisphere that could comfortably accommodate a vessel the size of CVA-58. Today, Newport News is the birthplace of the modern Gerald R. Ford class supercarrier. All the pomp and circumstance was at the ready in Newport News on April 19th, 1949, the day the Navy celebrated the keel-laying for CVA-58. By all measures, it looked like the USS United States would be sailing by the early 1950s with sister ships soon to come.

But just five measly days later, as work had already begun building upon CVA-58's keel, President Truman's Secretary of Defense Louis A. Johnson announced that all work on the project was to cease with immediate effect. To add to the Navy's misery, their projected fleet of nuclear-capable strategic jet bombers would die with the ship. In a seething rage, then Secretary of the Navy John Sullivan abruptly resigned, much to Secretary Johnson's annoyance, whom Sullivan accused of canning CVA-58 and allocating the Pentagon's nuclear bombers to the Air Force strictly for self-serving political reasons.

The subsequent squabble between the US Navy, Air Force, and Congress came to be known as the "Revolt of the Admirals," and while CVA-58 was a primary impetus for the considerable bad blood between all parties, the wide-stretching debate encompassed the collective frustrations of all branches involved. In the end, CVA-58's keel was scrapped while the Air Force and Navy bickered over how to proceed.

That was, up until the start of the Korean War, which put these arguments on the back burner, ensuring the Air Force and Navy would continue to be at odds with one another well into the 50s and 60s. Some might even argue they've been duking it out clandestinely ever since. In any case, the level of dysfunction attributed to just a single aircraft carrier can not be underestimated. In fact, it's a large portion of why the Air Force and Navy operate in the manner they do today. Even after 70 years, some aspects of the military-industrial complex have never changed. Eisenhower tried to warn us, after all, if only we'd listened.

Let us paint the scene for you. It's the mid-1940s. Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan lie in ruins, along with most of Central and Eastern Europe and a decent part of East Asia. Emerging from the smoke relatively unscathed was the United States Military, now the pre-eminent power in global geopolitics. In the immediate aftermath of the war, the pecking order for all of the U.S. Military's branches was largely set in stone. The Army had domain over the nation's ground forces, tanks, infantry, and so on, not handled by the Marine Corps. It also held total dominion over its land-based aircraft through the Army Air Corps.

Meanwhile, the US Navy, with battleships, destroyers, subs, aircraft carriers, and all, controlled the airspace along any maritime route its ships may travel. Yes, the Coast Guard and Marines were there as well. But it was clear which two branches wore the pants in the years following President Harry S. Truman's first proper administration. Or, at least, it was this way for a couple of years after the war.

With the National Security Act of 1947 signed in September of that year, the Army Air Corps re-organized formally into the US Air Force, and boy-howdy, did they have plans ready to royally tick off the Navy. The cornerstone of the Air Force's nuclear doctrine in the very early Cold War was long-range, land-based strategic bombers, which, at least in the Air Force's mind at the time, were essentially impervious to enemy fighters and could pierce enemy airspace with impunity before dropping nukes and flying home.

What Mitchser desired for the Navy was an aircraft carrier capable of launching nuclear-armed strategic jet bombers off its decks to attack military installations of the Soviet Union or its allies. Interestingly enough, for the atomic age, Navy top brass wished to keep the nukes attached to bombers instead of powering the ship itself, as they called for the proposed carrier to run on traditional boilers and steam turbines and have a range of around 12,000 nautical miles with a crew of 4,000 people. Further requests called for a flush-deck carrier deck design without an island center to allow for storing nuclear bombers with huge wingspans on deck.

Flush-deck carriers often require an auxiliary command ship to conduct the operations usually found on a carrier's command structure. These duties included radar warning detection to alert the supercarrier of incoming attacks. As a result, had it ever been built, the ship would've likely been unable to operate outside a Navy carrier strike group. Typically, these groups consist of at least one aircraft carrier flanked by a consortium of cruisers, destroyers, frigates, support ships, and the occasional group of submarines.

So to say, a lone wolf nation-crusher like modern US Navy carriers can be, this proposed ship was not. Even so, the Navy's strong desire to match the Air Force in nuclear bombing capability blinded them from blatant flaws in the design of their tentative new supercarrier. Dubbed the USS United States (CVA-58), and named for one of the first frigates built by the infant Congress back in 1794, the vessel was designed from the ground up to be a flagship for the entirety of the US Navy and named accordingly. With proposed dimensions of 1,090 feet (330 m) long with a 125-foot (38-m) beam at the waterline, the United States would've displaced as much as 83,200 tons when laden with crew, aircraft, and support vehicles.

Some reports even say the Douglas A3D Skywarrior was also slated for service aboard CVA-58. For defensive armament, a full battery of eight five-inch canons, 16 76-mm autocannons, and up to 20 smaller 20 mm Oerlikon anti-aircraft cannons for the small chance enemy aircraft are able to pierce CVA-58's airspace. In short, the ship would've been tough for the Soviets or any other fighting force to sink. Admiral Mitchser never lived to see his prized ship take place, as he died suddenly while on assignment in 1947. But as design work continued, it was decided that one American shipyard was the only facility fit for the job.

The yard in question was the famous Newport News Shipbuilding firm of Newport News, Virginia. The yard's been one of North America's premiere warship manufacturers since the late 1890s and was one of the only shipyards in the Western Hemisphere that could comfortably accommodate a vessel the size of CVA-58. Today, Newport News is the birthplace of the modern Gerald R. Ford class supercarrier. All the pomp and circumstance was at the ready in Newport News on April 19th, 1949, the day the Navy celebrated the keel-laying for CVA-58. By all measures, it looked like the USS United States would be sailing by the early 1950s with sister ships soon to come.

But just five measly days later, as work had already begun building upon CVA-58's keel, President Truman's Secretary of Defense Louis A. Johnson announced that all work on the project was to cease with immediate effect. To add to the Navy's misery, their projected fleet of nuclear-capable strategic jet bombers would die with the ship. In a seething rage, then Secretary of the Navy John Sullivan abruptly resigned, much to Secretary Johnson's annoyance, whom Sullivan accused of canning CVA-58 and allocating the Pentagon's nuclear bombers to the Air Force strictly for self-serving political reasons.

That was, up until the start of the Korean War, which put these arguments on the back burner, ensuring the Air Force and Navy would continue to be at odds with one another well into the 50s and 60s. Some might even argue they've been duking it out clandestinely ever since. In any case, the level of dysfunction attributed to just a single aircraft carrier can not be underestimated. In fact, it's a large portion of why the Air Force and Navy operate in the manner they do today. Even after 70 years, some aspects of the military-industrial complex have never changed. Eisenhower tried to warn us, after all, if only we'd listened.