At the end of last year, the famed Kennedy Space Center in Florida witnessed the launch of a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket carrying with it something called IXPE. That’s short for Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer, a space observatory like no other before it.

Described by NASA as a new set of eyes that could look into the depths of the Universe, from an altitude of 370 miles (600 km) above our planet’s equator, IXPE has one important mission: to look for “the remnants of exploded stars, powerful particle jets spewing from feeding black holes, and much more,” and the X-rays they are known to emit.

To do that, it has to try something that was never attempted before, and that is to see the polarization of X-rays. In doing so, it should answer some questions that have tormented astronomers for generations. In case you’re wondering why the study of X-rays is important, here’s a quick rundown of what they are and how they can tell us more about the Universe.

Described as a form of high-energy light, cosmic X-rays come to be in “places where matter is under extreme conditions – violent collisions, enormous explosions, 10-million-degree temperatures, fast rotations, and strong magnetic fields,” according to the American space agency.

We don’t get to properly see such manifestations here on Earth because the atmosphere acts like sort of force shield, not allowing them through. This is why observation of X-rays can properly be done only from space.

NASA already has a dedicated X-ray observatory in space, Chandra, but that can only detect the interconnected waves of electric and magnetic fields that vibrate, at right angles to the path the light is traveling, moving up and down, side to side, and pretty much in every direction conceivable.

Once X-rays hit something and pass through it, complete with information about the strange phenomena that produced them in the first place, the electric fields start vibrating in just one direction, and that’s called polarization. Chandra can’t detect that, but IXPE can, and its contribution to space exploration will be a better understanding of the sources for cosmic X-rays, something that can’t be achieved with brightness and color spectrum alone.

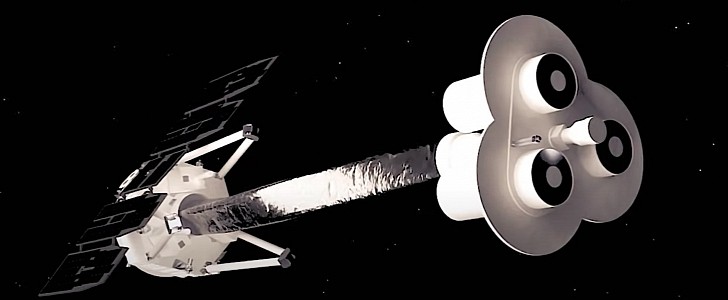

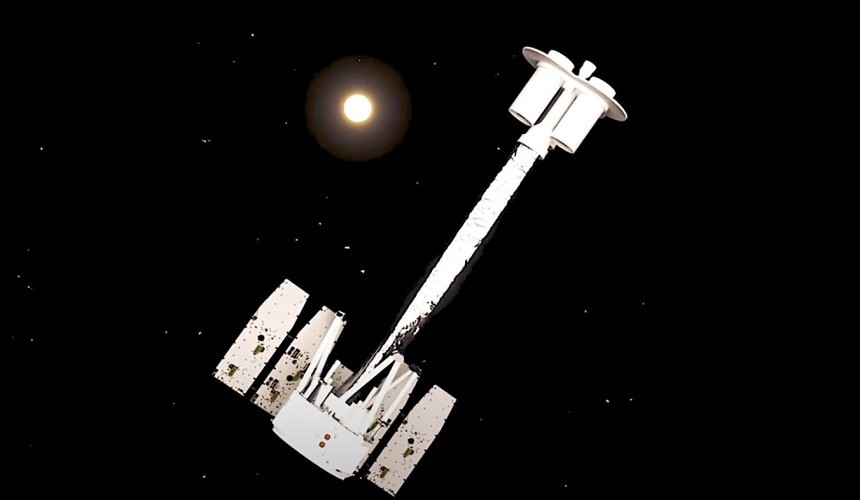

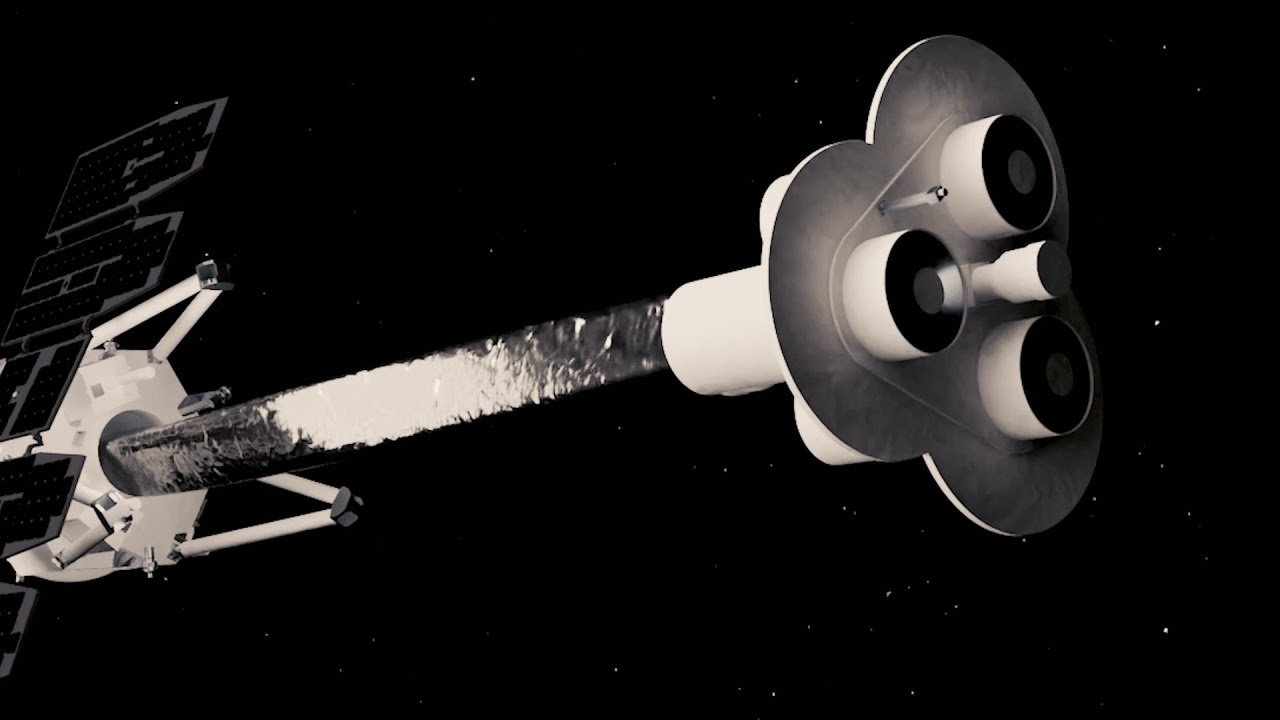

IXPE, created by NASA, the Italian Space Agency, and Ball Aerospace, is in fact a big extendable boom that holds solar panels and other pieces of hardware at one end, and three telescopes at the other. Each of the telescopes comprises a set of 24 nested, cylinder-shaped mirrors to collect X-rays, and a detector to snap images of incoming X-rays and measure the amount and direction of polarization.

Now that it has been launched, plans are to have the hardware up in orbit for the next two years, during which time it should be looking at some 50 bright objects, including leftovers of huge stars that went supernovae, the black hole we believe holds our galaxy together, and pulsars, among other things.

Theoretically, after combing through whatever data becomes available once IXPE really gets going, scientists should be able to “learn more about the structure and behavior of celestial objects, their surrounding environments, and the physics of how X-rays come to be,“ and get some answers to questions such as what is the spin of a black hole, or why pulsars are so bright.

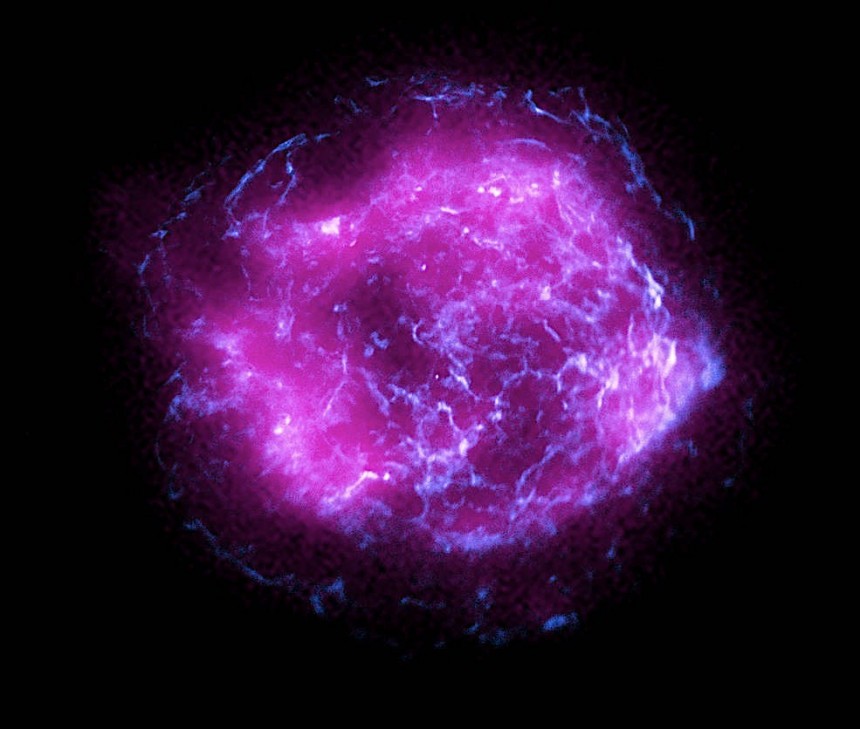

Back in February 2022, IXPE sent back its first science image, a snapshot of Cassiopeia A, the 10-light years in diameter remnant of a star that went bust in the 17th century. That’s a place other telescopes have looked at before, but the new data should help us better understand how X-rays are produced at Cassiopeia A.

To do that, it has to try something that was never attempted before, and that is to see the polarization of X-rays. In doing so, it should answer some questions that have tormented astronomers for generations. In case you’re wondering why the study of X-rays is important, here’s a quick rundown of what they are and how they can tell us more about the Universe.

Described as a form of high-energy light, cosmic X-rays come to be in “places where matter is under extreme conditions – violent collisions, enormous explosions, 10-million-degree temperatures, fast rotations, and strong magnetic fields,” according to the American space agency.

We don’t get to properly see such manifestations here on Earth because the atmosphere acts like sort of force shield, not allowing them through. This is why observation of X-rays can properly be done only from space.

Once X-rays hit something and pass through it, complete with information about the strange phenomena that produced them in the first place, the electric fields start vibrating in just one direction, and that’s called polarization. Chandra can’t detect that, but IXPE can, and its contribution to space exploration will be a better understanding of the sources for cosmic X-rays, something that can’t be achieved with brightness and color spectrum alone.

IXPE, created by NASA, the Italian Space Agency, and Ball Aerospace, is in fact a big extendable boom that holds solar panels and other pieces of hardware at one end, and three telescopes at the other. Each of the telescopes comprises a set of 24 nested, cylinder-shaped mirrors to collect X-rays, and a detector to snap images of incoming X-rays and measure the amount and direction of polarization.

Now that it has been launched, plans are to have the hardware up in orbit for the next two years, during which time it should be looking at some 50 bright objects, including leftovers of huge stars that went supernovae, the black hole we believe holds our galaxy together, and pulsars, among other things.

Back in February 2022, IXPE sent back its first science image, a snapshot of Cassiopeia A, the 10-light years in diameter remnant of a star that went bust in the 17th century. That’s a place other telescopes have looked at before, but the new data should help us better understand how X-rays are produced at Cassiopeia A.