Until something better and too far-fetched for us to consider at this time comes along, things leaving our planet will need rockets to do so. And those rockets will need fuel, which has to be stored somewhere and then burned through what can only be considered as controlled explosions. That’s the way they’ve been doing things for decades, and there seems little can be done to change that. Or can it?

At the moment, humanity can’t look past rockets to get off the planet. Sure, the sci-fi world has envisioned things like space elevators, or teleportation, or planet-bound wormholes, but until a breakthrough happens, we’re stuck with trying to make rockets as efficient as possible.

And one thing to take into account when thinking about efficiency is weight. Present-day rockets, no matter who makes them, rely on tanks, which are nothing more than pressurized containers needed to store the fuel. Generally, these tanks are made of aluminum alloys or steel, because there’s no way around them at the moment, or use metal as lining. And they are heavy.

But that may change soon, if research currently being conducted over in Europe comes to fruition. There, a team from MT Aerospace looked at some older studies, then worked their own magic, and apparently came up with a new design for carbon fiber reinforced plastic (CFRP) fuel tanks.

Now, you all know CFRP, that wonderful material used in pretty much everything nowadays, from the aerospace industry to car manufacturing. What we generally don’t make solely in CFRP are fuel tanks, especially ones for rockets, because the material is not entirely leak-tight in certain conditions.

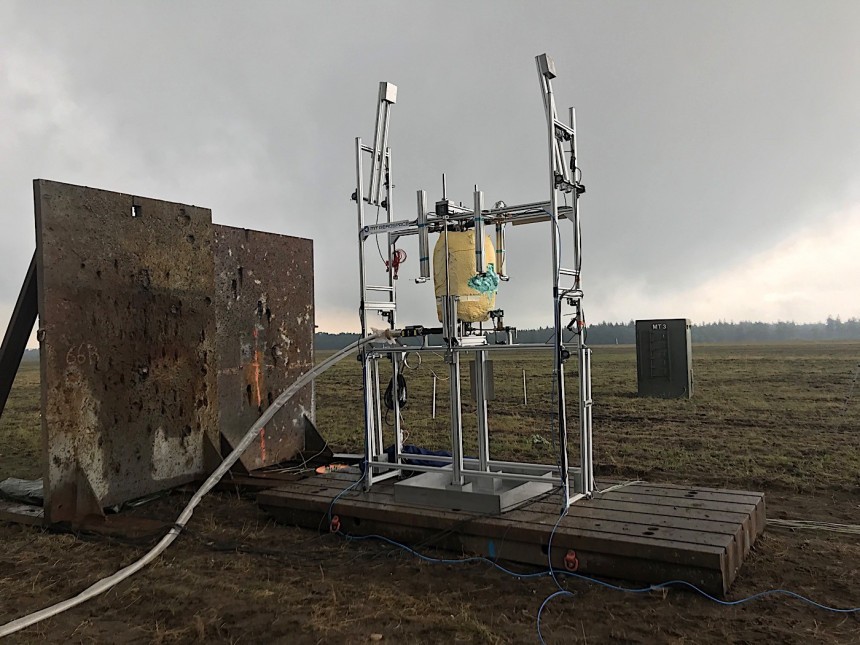

The German team apparently found a way to recreate the leak-tight properties of metal in a small-scale tank made of CFRP. They did this by using “a complex weave of black carbon fiber and a special resin.”

Now, that might not be very impressive, but the next bit is. During tests the team found that this “specific carbon composite and processing method” can not only keep every single ounce of liquid hydrogen in, but also survives being filled with liquid oxygen, despite having no metal liner to back it up.

To give you a sense of what that means, remember that the temperature of cryogenic propellants in a rocket fuel tank can reach minus 235 degrees Celsius (minus 391 degrees Fahrenheit), and only a metal liner on the tank could keep that tightly sealed in there. Until now, that is.

“The material resisted cryogenic temperatures, pressure cycles and reactive substances over a number of separate tests,” said MT Aerospace’s CEO Hans Steininger when the discovery was announced earlier this month.

The advantages of having a rocket fuel tank made of CFRP, and with no metal, are of course obvious. First would be a reduction in weight (no data on how much that would be on an average-sized rocket was provided), and weight is one of the most important aspects to be taken into account when launching stuff in orbit.

Then, such a tank would require fewer parts to be usable, thus making it easier to manufacture and operate. And, finally, the material might be used to come up with new designs, that are not possible using metals, for the upper stages of rockets.

So far, the only tests conducted on this new material were scale ones. MT plans to move on to testing the tanks with integrated thermal protection. Once that is out of the way, a full-scale demonstrator will be built.

The demonstrator is called Phoebus (which is an epithet of Greek god Apollo), and it will be 3.5 meters (11.4 feet) in diameter. It is scheduled for completion in 2023, and it will be used to “confirm the functional performance of the technologies and new cost-efficient production methods.”

If it works, it’ll probably soon turn into commonplace technology and sure, it may not be as spectacular as a space elevator, but it might very well contribute to humanity’s expansion into space.

And one thing to take into account when thinking about efficiency is weight. Present-day rockets, no matter who makes them, rely on tanks, which are nothing more than pressurized containers needed to store the fuel. Generally, these tanks are made of aluminum alloys or steel, because there’s no way around them at the moment, or use metal as lining. And they are heavy.

But that may change soon, if research currently being conducted over in Europe comes to fruition. There, a team from MT Aerospace looked at some older studies, then worked their own magic, and apparently came up with a new design for carbon fiber reinforced plastic (CFRP) fuel tanks.

Now, you all know CFRP, that wonderful material used in pretty much everything nowadays, from the aerospace industry to car manufacturing. What we generally don’t make solely in CFRP are fuel tanks, especially ones for rockets, because the material is not entirely leak-tight in certain conditions.

Now, that might not be very impressive, but the next bit is. During tests the team found that this “specific carbon composite and processing method” can not only keep every single ounce of liquid hydrogen in, but also survives being filled with liquid oxygen, despite having no metal liner to back it up.

To give you a sense of what that means, remember that the temperature of cryogenic propellants in a rocket fuel tank can reach minus 235 degrees Celsius (minus 391 degrees Fahrenheit), and only a metal liner on the tank could keep that tightly sealed in there. Until now, that is.

“The material resisted cryogenic temperatures, pressure cycles and reactive substances over a number of separate tests,” said MT Aerospace’s CEO Hans Steininger when the discovery was announced earlier this month.

Then, such a tank would require fewer parts to be usable, thus making it easier to manufacture and operate. And, finally, the material might be used to come up with new designs, that are not possible using metals, for the upper stages of rockets.

So far, the only tests conducted on this new material were scale ones. MT plans to move on to testing the tanks with integrated thermal protection. Once that is out of the way, a full-scale demonstrator will be built.

The demonstrator is called Phoebus (which is an epithet of Greek god Apollo), and it will be 3.5 meters (11.4 feet) in diameter. It is scheduled for completion in 2023, and it will be used to “confirm the functional performance of the technologies and new cost-efficient production methods.”

If it works, it’ll probably soon turn into commonplace technology and sure, it may not be as spectacular as a space elevator, but it might very well contribute to humanity’s expansion into space.