We're long past the days when we believed all the wonderful things that make up planet Earth were somehow born here, and that we're the center of the Universe. We now know everything from life itself to the elements that support it may just as well have originated elsewhere, and evidence of that keeps piling up.

Take water, for instance. There are several theories to it becoming a main element of our world, but the most widely accepted one is that water was already present in the planetesimals and other celestial objects that came together to form the planet itself, some 4.5 billion years ago.

If the theory is correct, then those water-rich planetesimals were most likely asteroids, as it's known that as they come closer to the Sun, comets are not favorable environments for such volatiles. You all know a comet's tail – that's frozen material, including water ice, that vaporizes when exposed to the heat of the Sun, and this process makes comets an unlikely source of water so deep into the solar system.

Sure, comets are known to have water, and lots of it. Until this week, it was generally believed that the stuff, in its frozen form, could only exist on comets located beyond the orbit of Neptune, in places so distant we can't even imagine: the Kuiper Belt and the Oort Cloud.

Much closer to home, inside the orbit of Jupiter and just past Mars, there's the mighty main asteroid belt. Like its name says, it is made of asteroids, old and of various types, many of which end up falling on neighboring Mars. But guess what: there are comets there too, and we've only begun finding out about their whereabouts and mysteries.

We know at the moment about just a handful of such comets. They're part of a new class of asteroid belt objects that, unlike asteroids, show a comet-like halo and tail.

Among the first such objects to be discovered, back in 2005, was Comet Read (238P/Read). It's a tiny piece of rock, just 0.6 km (0.4 miles) in diameter, that somehow, recently, fell under the scrutiny of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). And Webb turned the theory of asteroid belt comets not being able to hold water on its head a bit.

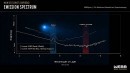

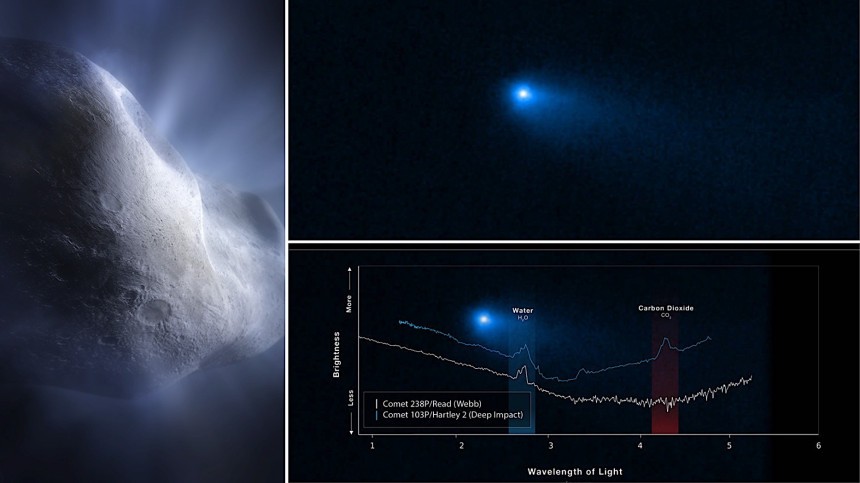

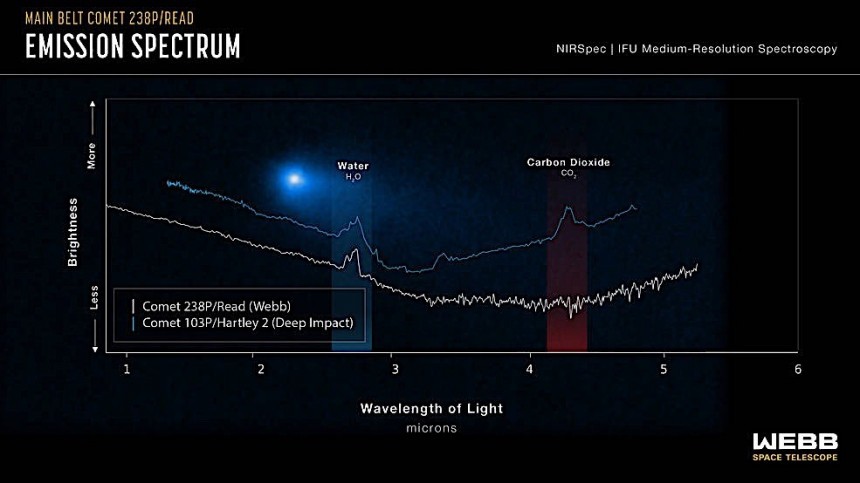

A comet's halo and tail I mentioned earlier come to pass through the evaporation of volatiles, including water ice and carbon dioxide. For a comet in the main asteroid belt to display them would mean these volatiles are present, and that's exactly what Webb was able to find on Read: water vapor.

According to the lead author of the study into the comet, University of Maryland's Michael Kelley, Webb has proven without a doubt that "yes, it's definitely water ice that is creating that effect."

And the presence of water ice on a comet so far into the solar system could lead to a better understanding of how water came to be on our planet. It could also point scientists in the right direction when looking at other solar systems as we look for signs of life and habitable planets.

As for carbon dioxide, which generally makes up ten percent or so of a comet's volatile material, well, that's completely absent from Comet Read. That's unusual, we're told, but could be explained by one of two phenomena.

The first is that, like most other comets, Read had the stuff, but, given how carbon dioxide vaporizes more easily than water ice when subjected to heat, and the comet's position in the solar system, it might have disappeared over the eons.

The second possible reason is that maybe Read didn't have carbon dioxide to begin with, as it might have formed in a region of the solar system that lacked this element, a so-called warm pocket.

Now that Webb has shed new light on yet another preconception of ours, the race is on to find more comets like Read in the asteroid belt.

Earlier this month, the organization tasked with running Webb's science work, the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), announced the programs that will be run during the telescope's Cycle 2, lasting from July 1, 2023 to June 30, 2024.

In all, the instruments now floating in space at a distance of 930,000 miles (1.5 million km) from home will be pointed at celestial objects that target 249 study ideas, worth a combined 5,000 hours of telescope time.

The list is thus very long, and it's unclear whether an asteroid belt comet is featured there. Generally, Cycle 2 will focus on asteroids, exoplanets, and cosmology, but all the things Webb sees over the coming year will be published in a publicly available archive.

And from there to another discovery such as the one we have here is only a matter of the right people diving into at the right things.

If the theory is correct, then those water-rich planetesimals were most likely asteroids, as it's known that as they come closer to the Sun, comets are not favorable environments for such volatiles. You all know a comet's tail – that's frozen material, including water ice, that vaporizes when exposed to the heat of the Sun, and this process makes comets an unlikely source of water so deep into the solar system.

Sure, comets are known to have water, and lots of it. Until this week, it was generally believed that the stuff, in its frozen form, could only exist on comets located beyond the orbit of Neptune, in places so distant we can't even imagine: the Kuiper Belt and the Oort Cloud.

Much closer to home, inside the orbit of Jupiter and just past Mars, there's the mighty main asteroid belt. Like its name says, it is made of asteroids, old and of various types, many of which end up falling on neighboring Mars. But guess what: there are comets there too, and we've only begun finding out about their whereabouts and mysteries.

We know at the moment about just a handful of such comets. They're part of a new class of asteroid belt objects that, unlike asteroids, show a comet-like halo and tail.

A comet's halo and tail I mentioned earlier come to pass through the evaporation of volatiles, including water ice and carbon dioxide. For a comet in the main asteroid belt to display them would mean these volatiles are present, and that's exactly what Webb was able to find on Read: water vapor.

According to the lead author of the study into the comet, University of Maryland's Michael Kelley, Webb has proven without a doubt that "yes, it's definitely water ice that is creating that effect."

And the presence of water ice on a comet so far into the solar system could lead to a better understanding of how water came to be on our planet. It could also point scientists in the right direction when looking at other solar systems as we look for signs of life and habitable planets.

As for carbon dioxide, which generally makes up ten percent or so of a comet's volatile material, well, that's completely absent from Comet Read. That's unusual, we're told, but could be explained by one of two phenomena.

The second possible reason is that maybe Read didn't have carbon dioxide to begin with, as it might have formed in a region of the solar system that lacked this element, a so-called warm pocket.

Now that Webb has shed new light on yet another preconception of ours, the race is on to find more comets like Read in the asteroid belt.

Earlier this month, the organization tasked with running Webb's science work, the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), announced the programs that will be run during the telescope's Cycle 2, lasting from July 1, 2023 to June 30, 2024.

In all, the instruments now floating in space at a distance of 930,000 miles (1.5 million km) from home will be pointed at celestial objects that target 249 study ideas, worth a combined 5,000 hours of telescope time.

The list is thus very long, and it's unclear whether an asteroid belt comet is featured there. Generally, Cycle 2 will focus on asteroids, exoplanets, and cosmology, but all the things Webb sees over the coming year will be published in a publicly available archive.

And from there to another discovery such as the one we have here is only a matter of the right people diving into at the right things.