January 8 marked the start of the first major space mission of the year. Something called the Peregrine Mission One departed from Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida, heading for the Moon with the first American lander to go up there since the Apollo program.

The lander is called Peregrine, it's made by a private company called Astrobotic, and it's scheduled to land in the Sinus Viscositatis region, on the near side of the Moon, in late February.

The mission is important in itself, as it will try to determine a series of things about our planet's natural satellite, including the presence of water, the composition of the Moon's thin atmosphere (yes, it has one, but only just), and set down a permanent location marker.

We've discussed the lander's missions at length earlier today, and you can read all about it here. This story is about something else entirely, something that kind of got lost in the excitement of the launch itself.

The Peregrine mission would not have been possible without a rocket to launch it into space. As it happens, the launch itself was a momentous occasion in the history of space exploration.

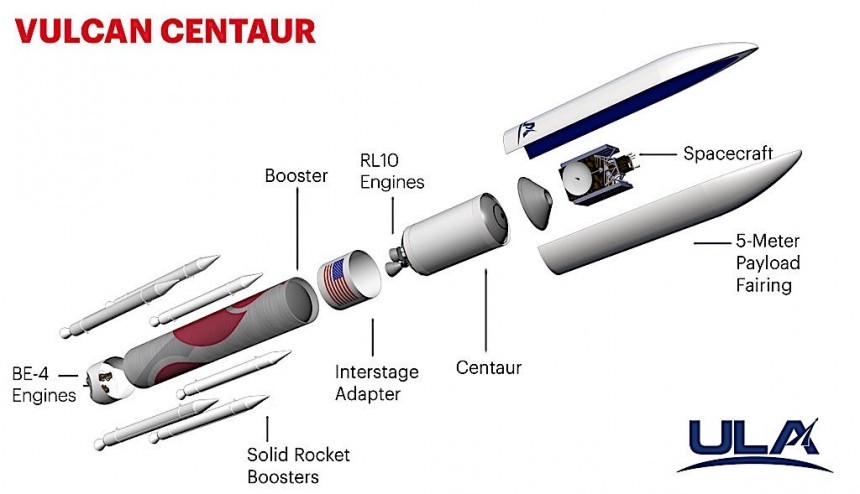

Today marked the first time a rocket called Vulcan Centaur left the pad. We're talking about a two-stage heavy-lift rocket made by talented crews over at United Launch Alliance (ULA).

The thing towers 202 feet (61 meters) off the ground and can carry a total of 26,700 pounds (12,100 kg) of cargo to a trans-lunar injection orbit.

It can do that thanks to a pair of Blue Origin-supplied engines, called BE-4, powering the first stage, each of them capable of developing 550,000 pounds and burning liquid natural gas (LNG) and oxygen.

The engines themselves are advertised by Jeff Bezos' company as the most powerful of their kind currently being produced in the U.S. They are backed by two Aerojet Rocketdyne RL10C engines pushing on the second stage, but also boosters the likes of which the world has never seen. And it is these boosters that are the center of our attention today.

The Vulcan Centaur that departed Florida a few hours ago had two boosters on, although the rocket has been built in such a way as to accommodate no less than six of them. And both were something that had never been flown before.

The hardware is made by Northrop Grumman and is of the monolithic variety, meaning solid rocket boosters (SRB). In words we can all understand, they are both made of a single piece, a method that has a series of advantages over a segmented approach. But more on that in a bit.

Each of the Peregrine mission's Graphite Epoxy Motors (GEM), as they're also called, has a diameter of 63 inches (160 cm) and measures a total of 72 feet (22 meters) in length. That makes them, by all accounts, "the longest monolithic SRB ever produced for flight," beating by far the previous record holder, which stood at just 66 feet (20 meters).

That previous rocket holder was called GEM 63, so the increase in size for the new iteration prompted Northrop Grumman to fittingly name the new SRBs GEM 63XL.

I said earlier we'll talk a bit about why making an SRB of this size in a single piece is important. First up, such an approach lowers the overall mass of the booster, and we all know how important that is when it comes to space launches.

Then, the motors themselves are a lot simpler, as there is no need for joints and other connecting hardware. This in turn allows the SRb to easily develop up to 463,000 pounds of thrust, but also helps with a more intensive launch schedule, as there are fewer parts that can potentially fail.

In the Vulcan Centaur, for instance, together with the BE engines, the full pack of six boosters can give the rocket to a total power of 3.3 million pounds of thrust, placing pretty much all imaginable orbits within reach.

In the coming years, as the world's space expansion accelerates and thanks to the ULA contract it signed back in 2022, Northrop Grumman will produce an increasing number of these boosters, which in themselves are not reusable.

As for the Vulcan Centaur rocket, it has only one more flight planned for this year (that may change by the end of the year, though). In April it will take off carrying Sierra Space's Dream Chaser spaceplane, sending it to the International Space Station (ISS), which in itself will be another premiere for the American space exploration program.

In the meantime, you can delight yourself with the rocket as it departed the launch pad this Monday, heading for an orbit that would allow America's first Moon mission to land up there in more than half a century.

The landing of the Peregrine on the Moon is scheduled to take place on February 23.

The mission is important in itself, as it will try to determine a series of things about our planet's natural satellite, including the presence of water, the composition of the Moon's thin atmosphere (yes, it has one, but only just), and set down a permanent location marker.

We've discussed the lander's missions at length earlier today, and you can read all about it here. This story is about something else entirely, something that kind of got lost in the excitement of the launch itself.

The Peregrine mission would not have been possible without a rocket to launch it into space. As it happens, the launch itself was a momentous occasion in the history of space exploration.

Today marked the first time a rocket called Vulcan Centaur left the pad. We're talking about a two-stage heavy-lift rocket made by talented crews over at United Launch Alliance (ULA).

The thing towers 202 feet (61 meters) off the ground and can carry a total of 26,700 pounds (12,100 kg) of cargo to a trans-lunar injection orbit.

The engines themselves are advertised by Jeff Bezos' company as the most powerful of their kind currently being produced in the U.S. They are backed by two Aerojet Rocketdyne RL10C engines pushing on the second stage, but also boosters the likes of which the world has never seen. And it is these boosters that are the center of our attention today.

The Vulcan Centaur that departed Florida a few hours ago had two boosters on, although the rocket has been built in such a way as to accommodate no less than six of them. And both were something that had never been flown before.

The hardware is made by Northrop Grumman and is of the monolithic variety, meaning solid rocket boosters (SRB). In words we can all understand, they are both made of a single piece, a method that has a series of advantages over a segmented approach. But more on that in a bit.

Each of the Peregrine mission's Graphite Epoxy Motors (GEM), as they're also called, has a diameter of 63 inches (160 cm) and measures a total of 72 feet (22 meters) in length. That makes them, by all accounts, "the longest monolithic SRB ever produced for flight," beating by far the previous record holder, which stood at just 66 feet (20 meters).

That previous rocket holder was called GEM 63, so the increase in size for the new iteration prompted Northrop Grumman to fittingly name the new SRBs GEM 63XL.

Then, the motors themselves are a lot simpler, as there is no need for joints and other connecting hardware. This in turn allows the SRb to easily develop up to 463,000 pounds of thrust, but also helps with a more intensive launch schedule, as there are fewer parts that can potentially fail.

In the Vulcan Centaur, for instance, together with the BE engines, the full pack of six boosters can give the rocket to a total power of 3.3 million pounds of thrust, placing pretty much all imaginable orbits within reach.

In the coming years, as the world's space expansion accelerates and thanks to the ULA contract it signed back in 2022, Northrop Grumman will produce an increasing number of these boosters, which in themselves are not reusable.

As for the Vulcan Centaur rocket, it has only one more flight planned for this year (that may change by the end of the year, though). In April it will take off carrying Sierra Space's Dream Chaser spaceplane, sending it to the International Space Station (ISS), which in itself will be another premiere for the American space exploration program.

In the meantime, you can delight yourself with the rocket as it departed the launch pad this Monday, heading for an orbit that would allow America's first Moon mission to land up there in more than half a century.

The landing of the Peregrine on the Moon is scheduled to take place on February 23.