Earlier in April news broke of a British company called Space Solar reaching an important milestone in its race to become the first to harness solar power in space and send it back to Earth for our daily use. That bit of news opened our appetite for more details on the topic, and what do you know: the European Space Agency (ESA) delivered.

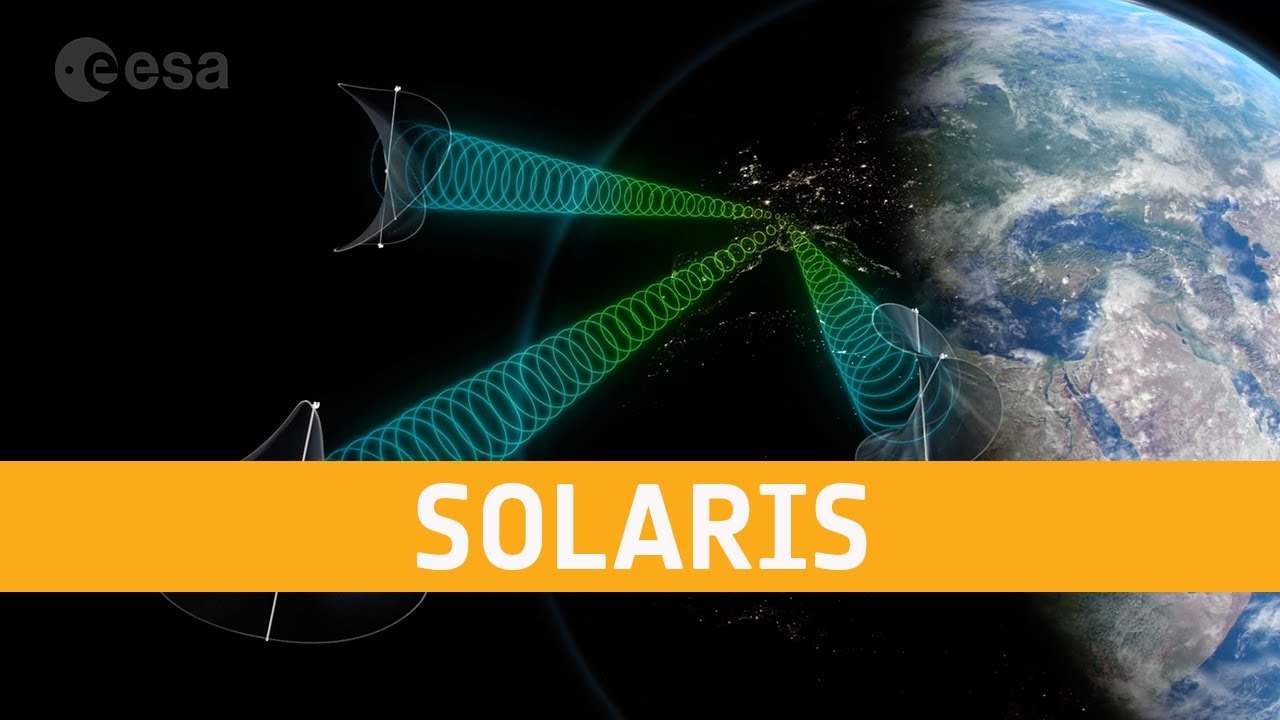

As American NASA continues to lead humanity's space exploration efforts, ESA is quickly catching up and has a number of very interesting and high-profile projects up its sleeve. One of them is called Solaris and yes, it has to do with Space-Based Solar Power.

That's SBSP for short, a concept that has been around for quite some time. It was first proposed by Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky in 1923, and at the time it involved sending ten-square-meter (108 square feet) mirrors to space to redirect sunlight to the surface in the form of strong beams. Strong enough, as per Tsiolkovsky, to be able to heat up ten large cups of coffee in under two minutes.

The idea was pretty wacky but interesting enough that many others gave it a closer look over the years. For various reasons, none of the subsequent research stuck, so not even today, at the peak of our civilization, we can't make use of SBSP.

We did, however, learn to use the Sun's power. We are capturing its light with solar panels and converting that into green electricity on an increasingly larger scale. It's a system that works, but it is highly inefficient, and it will never be enough to singlehandedly satisfy our electricity needs.

Why is that? First of all, we're not capturing the full power of the Sun, but only a fraction of it. In the upper layers of the atmosphere, sunlight is about ten times more powerful than it is on the ground, where the solar panels are located.

Then, no matter how willing the Sun is to share its resources with us, the Earth's atmosphere, its clouds, and the rotation that always hides one face of the planet from the star severely impact how much electricity solar panels can generate.

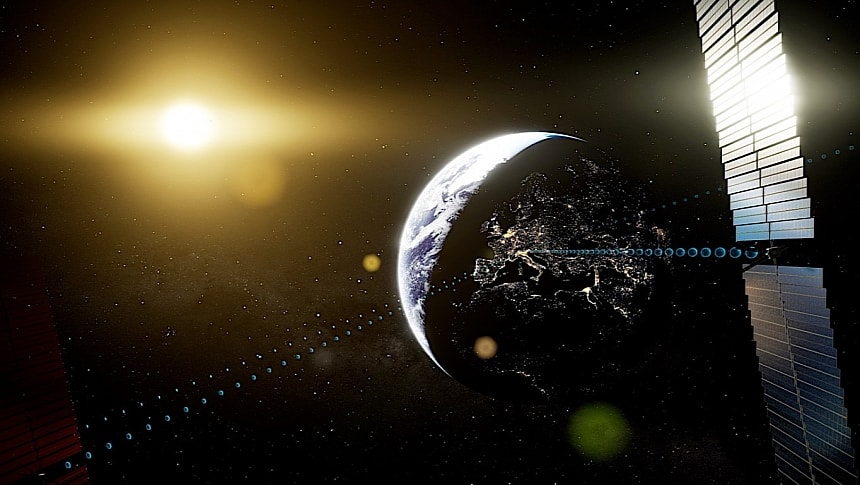

Placing solar panels in space would pretty much solve all of those issues. In fact, we're already doing that, but the panels currently deployed in orbit are only used to feed the spacecraft they're attached to. And none of these spacecraft can beam down to Earth the power they capture.

ESA plans to change that, and it's so serious about it that in 2022 it launched the aforementioned Solaris initiative. In a nutshell, we're talking about a concerted effort from European agencies, companies, and regulators to research the topic and inform a continent-wide decision in 2025 meant to support the creation and deployment of SBSP satellites.

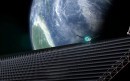

Previous research into this field produced several ways of harnessing and wirelessly sending electricity from space, and ESA is looking at a couple of them at the same time.

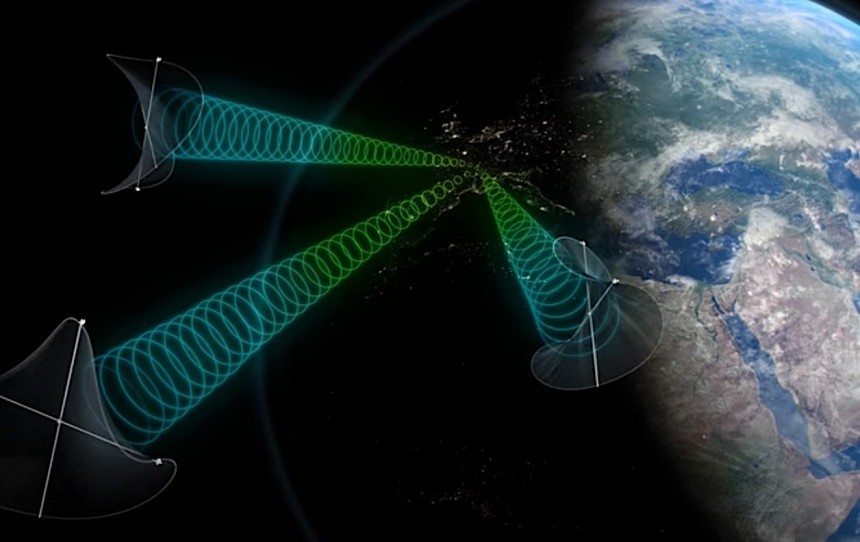

The first would be using photovoltaic cells placed in geostationary orbit to capture sunlight, and dedicated receiver stations on Earth to capture it when it will be sent down in 2.45 GHz microwave form. The receivers, called rectennas, would be capable of converting the microwaves to electricity and feeding it to the grid.

Such an approach has a series of advantages. First up, it's something we can achieve with the technology currently at our disposal, because we already have the tools to make it happen. Then, power harvested this way could just as easily be sent to the Moon, Mars, and elsewhere, not only our home planet.

But there is one major disadvantage: such a design would need to be massive to work. ESA says that to be able to generate "optimal, economically-viable levels of solar power" the satellite would need to one km (0.62 miles) across, and the rectennas more than ten times as large.

The second approach would be to follow up on Tsiolkovsky idea and use mirrors instead of solar panels. These pieces of hardware would do nothing more than reflect sunlight to the solar panels located on the ground, in a much larger quantity than naturally possible.

This approach is even easier to implement than the previous one, but its main downside is that, well, we'll have giant mirrors floating in space reflecting sunlight in our eyes.

ESA is equally as serious about these ideas, though, and it has already tasked companies by Arthur D Little and Thales Alenia Space Italy with looking closer into them. Both should have completed their work by the end of last year, but we're still waiting on the results.

ESA is presently trying to sell the Solaris initiative to interested parties at the International Conference on Energy from Space taking place this week in London. We don't know yet what facts it will use to hook more people into this project, but we do know why everyone should be hyped at the prospect of SBSP.

Consider this: a satellite one km across could give us around two gigawatts of power directly from space. That's more than enough to power one million homes for a long period of time. Two gigawatts is what most conventional nuclear power stations are capable of delivering, but far beyond what Earth-based solar panels can do: you'd need around six million of them to generate as much.

It will probably be a long time still before we get to enjoy electricity beamed down from space, but the steps ESA and its partners are taking to make this a reality of our world kind of make us confident we could see a major breakthrough soon enough.

That's SBSP for short, a concept that has been around for quite some time. It was first proposed by Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky in 1923, and at the time it involved sending ten-square-meter (108 square feet) mirrors to space to redirect sunlight to the surface in the form of strong beams. Strong enough, as per Tsiolkovsky, to be able to heat up ten large cups of coffee in under two minutes.

The idea was pretty wacky but interesting enough that many others gave it a closer look over the years. For various reasons, none of the subsequent research stuck, so not even today, at the peak of our civilization, we can't make use of SBSP.

We did, however, learn to use the Sun's power. We are capturing its light with solar panels and converting that into green electricity on an increasingly larger scale. It's a system that works, but it is highly inefficient, and it will never be enough to singlehandedly satisfy our electricity needs.

Then, no matter how willing the Sun is to share its resources with us, the Earth's atmosphere, its clouds, and the rotation that always hides one face of the planet from the star severely impact how much electricity solar panels can generate.

Placing solar panels in space would pretty much solve all of those issues. In fact, we're already doing that, but the panels currently deployed in orbit are only used to feed the spacecraft they're attached to. And none of these spacecraft can beam down to Earth the power they capture.

ESA plans to change that, and it's so serious about it that in 2022 it launched the aforementioned Solaris initiative. In a nutshell, we're talking about a concerted effort from European agencies, companies, and regulators to research the topic and inform a continent-wide decision in 2025 meant to support the creation and deployment of SBSP satellites.

Previous research into this field produced several ways of harnessing and wirelessly sending electricity from space, and ESA is looking at a couple of them at the same time.

Such an approach has a series of advantages. First up, it's something we can achieve with the technology currently at our disposal, because we already have the tools to make it happen. Then, power harvested this way could just as easily be sent to the Moon, Mars, and elsewhere, not only our home planet.

But there is one major disadvantage: such a design would need to be massive to work. ESA says that to be able to generate "optimal, economically-viable levels of solar power" the satellite would need to one km (0.62 miles) across, and the rectennas more than ten times as large.

The second approach would be to follow up on Tsiolkovsky idea and use mirrors instead of solar panels. These pieces of hardware would do nothing more than reflect sunlight to the solar panels located on the ground, in a much larger quantity than naturally possible.

This approach is even easier to implement than the previous one, but its main downside is that, well, we'll have giant mirrors floating in space reflecting sunlight in our eyes.

ESA is presently trying to sell the Solaris initiative to interested parties at the International Conference on Energy from Space taking place this week in London. We don't know yet what facts it will use to hook more people into this project, but we do know why everyone should be hyped at the prospect of SBSP.

Consider this: a satellite one km across could give us around two gigawatts of power directly from space. That's more than enough to power one million homes for a long period of time. Two gigawatts is what most conventional nuclear power stations are capable of delivering, but far beyond what Earth-based solar panels can do: you'd need around six million of them to generate as much.

It will probably be a long time still before we get to enjoy electricity beamed down from space, but the steps ESA and its partners are taking to make this a reality of our world kind of make us confident we could see a major breakthrough soon enough.