No matter how you twist this, America is for now the country that has sent the most missions to the Moon. Even so, the nation that led humanity's charge into space long ago is also the same one that has sent over the past few years several missions to Mars, and absolutely none to the Moon.

The Peregrine lander was supposed to change that. It was to be the United States' first mission to the planet's natural satellite in more than half a century, a precursor of the mighty (and now significantly delayed) Artemis program.

It was also to be the first lunar lander tech developed by a private company to set down on the Moon, as until now only government-backed hardware from the U.S., Soviet Union, China, and India has managed to do it.

And it was also supposed to perform bucketloads of science. With five important instruments on board, the Peregrine was to give us a more intimate look at the place some of us might soon call a second home.

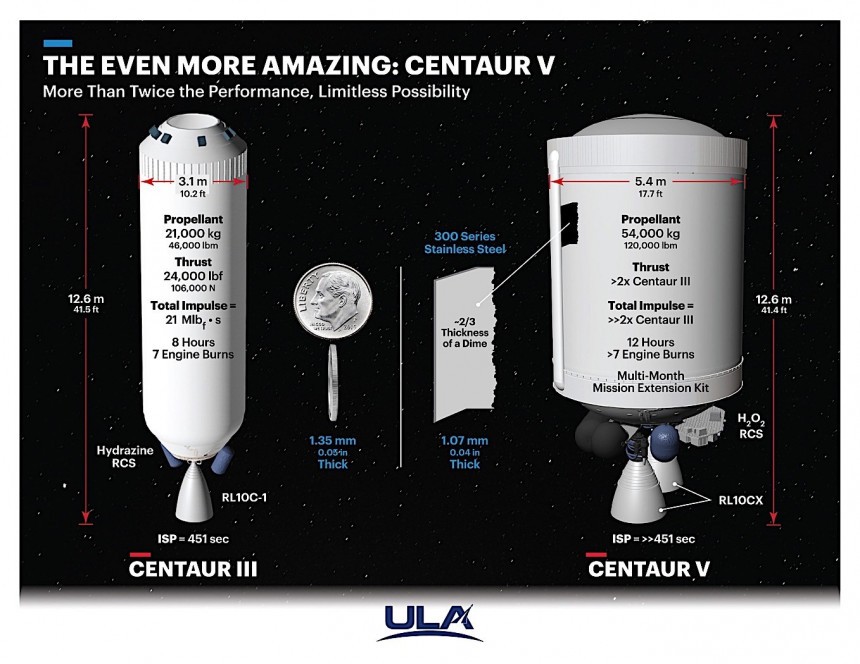

The lander launched from Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida on Monday, January 8. It was carried into space by a brand new rocket, the mighty Vulcan Centaur. Developed by the United Launch Alliance (ULA), the rocket became the one rocking the longest single-segment boosters ever to be flown: 72 feet (22 meters) in length.

The launch was flawless, and hopes were high about the success of the daring flight. After a trip that was to take more than a month, the Peregrine was to land in the Sinus Viscositatis region, and start doing science there.

But it failed.

That became apparent as soon as the first images the spacecraft snapped in space arrived on Earth. And what was a fear soon became a certainty: the Peregrine had suffered a catastrophic failure.

A fuel leak, whose underlying causes are yet unknown (probably a ruptured tank, but no one knows why it ruptured), robbed the spacecraft of its ability to position itself in such a way for the solar panels it carries to face the Sun. Thrusters failed, and a fight to keep the Peregrine from going into a tumble began.

Soon after launch, the plan of setting the lander down on the surface of the Moon was scrubbed. Astrobotic, the company that made it, and NASA, which had a vested interest in it, decided to point it at the Moon and keep going for as long as it's possible. The goal: to gather as much data as possible before the end of the mission.

And data gathering is exactly what the Peregrine did. Despite having been intended for operation on the surface, all but one of the instruments were powered on during flight, and that allowed operators to still get something out of the mission.

We're not told exactly how much data was collected, but it's enough for the interpretation of the results to take "some time." We do know we have info on the amount of radiation that can be found in the space between the Earth and the Moon, on the presence of chemical compounds out there (some of which probably came from the lander's own fuel leak), and even on space weather.

Although it was not exactly the mission people had been training for, the short-lived Peregrine mission did manage to achieve another important thing: it validated new technologies for space exploration, as well as data processing methods and operational procedures. All of this, says the American space agency, "will improve NASA's ability to map the lunar surface in the future."

We're talking about the Peregrine once more because its story abruptly ended this week, in a fiery crash back to Earth that no one on this planet was in a position to witness.

When they realized they got the most out of the mission, controllers decided to kill it by going for a re-entry. The procedure started on Thursday, January 18, at 4 pm EST, and ended shortly after, when a tracking station in Canberra, Australia confirmed the loss of signal with the spacecraft.

The crash was a controlled one, with Peregrine aimed at a remote area of the South Pacific, with zero chances of debris reaching land. It's likely none of it survived the fiery trip through Earth's atmosphere.

Later on Friday (January 19, 1 pm EST) NASA will hold a media briefing to provide an “end of mission update.” It's unlikely we'll learn something new, but we'll keep an eye out and update this story with relevant information, if any.

Until that time, even if the actual re-entry was not captured on film, Peregrine did record images of planet Earth as it departed a couple of weeks ago. You can enjoy it below as a sort of farewell from the first failed space mission of the year.

It was also to be the first lunar lander tech developed by a private company to set down on the Moon, as until now only government-backed hardware from the U.S., Soviet Union, China, and India has managed to do it.

And it was also supposed to perform bucketloads of science. With five important instruments on board, the Peregrine was to give us a more intimate look at the place some of us might soon call a second home.

The lander launched from Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida on Monday, January 8. It was carried into space by a brand new rocket, the mighty Vulcan Centaur. Developed by the United Launch Alliance (ULA), the rocket became the one rocking the longest single-segment boosters ever to be flown: 72 feet (22 meters) in length.

The launch was flawless, and hopes were high about the success of the daring flight. After a trip that was to take more than a month, the Peregrine was to land in the Sinus Viscositatis region, and start doing science there.

But it failed.

A fuel leak, whose underlying causes are yet unknown (probably a ruptured tank, but no one knows why it ruptured), robbed the spacecraft of its ability to position itself in such a way for the solar panels it carries to face the Sun. Thrusters failed, and a fight to keep the Peregrine from going into a tumble began.

Soon after launch, the plan of setting the lander down on the surface of the Moon was scrubbed. Astrobotic, the company that made it, and NASA, which had a vested interest in it, decided to point it at the Moon and keep going for as long as it's possible. The goal: to gather as much data as possible before the end of the mission.

And data gathering is exactly what the Peregrine did. Despite having been intended for operation on the surface, all but one of the instruments were powered on during flight, and that allowed operators to still get something out of the mission.

We're not told exactly how much data was collected, but it's enough for the interpretation of the results to take "some time." We do know we have info on the amount of radiation that can be found in the space between the Earth and the Moon, on the presence of chemical compounds out there (some of which probably came from the lander's own fuel leak), and even on space weather.

Although it was not exactly the mission people had been training for, the short-lived Peregrine mission did manage to achieve another important thing: it validated new technologies for space exploration, as well as data processing methods and operational procedures. All of this, says the American space agency, "will improve NASA's ability to map the lunar surface in the future."

We're talking about the Peregrine once more because its story abruptly ended this week, in a fiery crash back to Earth that no one on this planet was in a position to witness.

When they realized they got the most out of the mission, controllers decided to kill it by going for a re-entry. The procedure started on Thursday, January 18, at 4 pm EST, and ended shortly after, when a tracking station in Canberra, Australia confirmed the loss of signal with the spacecraft.

The crash was a controlled one, with Peregrine aimed at a remote area of the South Pacific, with zero chances of debris reaching land. It's likely none of it survived the fiery trip through Earth's atmosphere.

Later on Friday (January 19, 1 pm EST) NASA will hold a media briefing to provide an “end of mission update.” It's unlikely we'll learn something new, but we'll keep an eye out and update this story with relevant information, if any.

Until that time, even if the actual re-entry was not captured on film, Peregrine did record images of planet Earth as it departed a couple of weeks ago. You can enjoy it below as a sort of farewell from the first failed space mission of the year.

(2/2)Peregrine captured this video moments after successful separation from @ulalaunch Vulcan rocket. Counterclockwise from top left center is the DHL MoonBox, Astroscale's Pocari Sweat Lunar Dream Time Capsule, & Peregrine landing leg. Background: our big blue marble, Earth! pic.twitter.com/1y4OsosNDp

— Astrobotic (@astrobotic) January 19, 2024