What qualities come to mind when you think of the archetypical big American internal combustion engine? Is it giant, hulking leviathans where anything less than eight cylinders is paramount to commie propaganda? You know, the kind of machines that fight America's longest running anatomy-measuring competition with cubic displacement and not much else? The stuff under the hoods of late 60s and contemporary muscle cars. From at least one point of view, the common ancestor of this distinctly American philosophy for internal combustion was built for the air, not the dragstrip.

This is the story of the Allison V-1710. If the comparison between a World War II aero engine and the one you find in a 60s muscle car is weird to you, trust us, it'll all make sense in time. Though not configured in that typical arrangement of eight cylinders in a vee-formation that makes an American's brain go fuzzy, the V-1710 checked all the other boxes for an all-time great American engine. You know, a cubic capacity that seems more fit for a ship than a car or aircraft, a curb weight a fair percentage of an entire passenger car, and a power output that gave Axis Air Forces cause for concern.

The V-1710's story is one that's routinely overlooked in favor of the later, more powerful Rolls-Royce/Packard Merlin V12. But in so many ways, the V-1710 was an engine that could have only been built in America. To understand the roots of Allison's most famous engine, we need to go back to well before World War II, to a time when the United States was still trying to prove itself to other aircraft-producing nations of Europe despite being the first to put men in the air. In the time before the proverbial Pax Americana after the two World Wars, such conditions were often the case. Around this time, the company's founder, James A. Allison, made most of his business through the precision manufacturing of race car components at his workshop a short distance away from the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in Speedway, Indiana.

Allison even maintained a shop on Speedway grounds for a time, and his racing hardware became a mainstay at early runnings of the Indy 500 before Europe's great powers decided to boogaloo in 1914. During World War I, the company was instrumental in the development of the Liberty V12 aero engine that, while innovative for the time and the first American liquid-cooled aero engine built during wartime, found itself obsolete soon after the Armistice of 1918. Allison's bespoke production run of inverted L-12s, the VG-1410, was among the first to adopt early adaptations of geared superchargers in the very late1910s.

Soon after the Liberty L-12 grew obsolete in the mid-to-late 20s, the hunt was on to build the next generation of bonkers, high-output American aero engines to define the United States on the global aeronautical stage through the U.S. Army's "Hyper Engine" program. At first, Allison's manager, Norman Gilman, started work on a particularly ridiculous air-cooled, 24-cylinder engine arranged in an X-formation and called the X-4250. When the proposal for this design reached the Army's desk and made their collective brains melt, Allison promptly went back to the drawing board in search of a more conventional design.

The initial target aircraft for Allison's tentative design was the U.S. Navy's line of Akron-class airship vehicles. Sadly, the crash and destruction of the USS Macon and USS Akron in 1931 and 1933 before the engine was ready scrapped these plans. Both airships went to their graves sporting German Maybach engines. Soon afterward, James A. Allison passed away, and his company was sold first to a consortium headed by WWI flying ace and race car driver Eddie Richenbacher before being flipped to the Fisher Body Company. Before long, the economic stresses of the Great Depression caused Fisher to sell the Allison Engine Company to General Motors, who bankrolled their engine research into what ultimately became the V-1710.

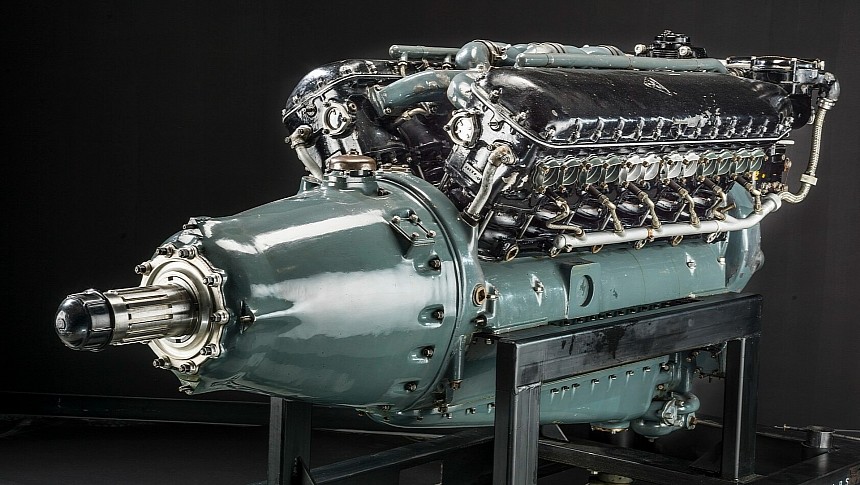

From the rib of Allison's concept airship engine, components like the cylinders, single-overhead camshaft, and ethylene glycol liquid cooling system gave unmistakable qualities to the V-1710 V12. If the Liberty L-12 was a giant engine with limited horsepower potential, the V-1710 used the lessons learned over a decade of innovation to build an even larger motor, much more suited to delivering high horsepower figures as the U.S. Army Air Corps and Navy demanded. With 12 cylinders arranged at 65 degrees and a displacement of 1,710.6 cu in (28.032 L), the V-1710 was among the first aeronautical engines to crack the magic 1000-horsepower boundary behind the bonkers Napier Cub X-16 of Great Britain.

Like a performance crate engine in a modern restomod, the V-1710 was designed around a modular platform. Wherein a basic power section with a core nucleus of engine components assembled around the block could be altered with secondary hardware like forced induction to squeeze even more performance out of the design. With the blueprints now set in stone and a small initial production run complete, the V-1710 made its first trip into the air on December 14th, 1936, under the hood of a Consolidated XA-11A mono-wing fighter. Before long, the V-1710 was marked as the standard-issue liquid-cooled inline engine for America's emerging breed of advanced piston fighters.

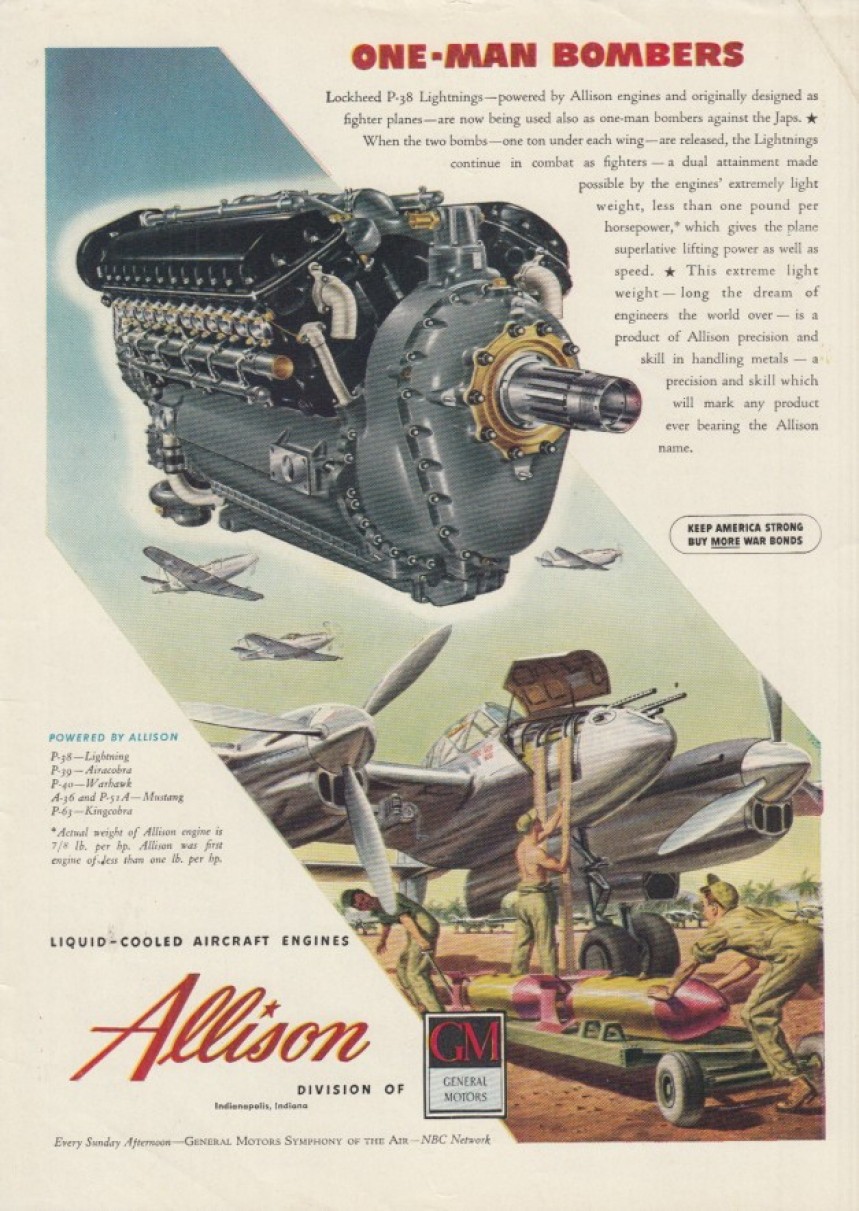

From the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk to the Lockheed P-38 Lightning twin-engine fighter and even the mid-engined Bell P-39 Airacobra, all utilized Allison V-1710s in various configurations during the Second World War. Thanks to the platform's modular design, adapting the V-1710 to accommodate novel forms of forced induction was relatively easy. To the point that both the original XP-38 and later serial P-38 models flew with sophisticated General Electric B-5 turbo-superchargers, which used both a geared connection to the engine as well as residual exhaust gasses as a means of forced induction. The V-1710 was even trialed on the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress quad-engine bomber for a time to test the platform's adaptability with powertrains other than the standard Wright R-1820 nine-cylinder radials.

While the V-1710 proved to be a hearty engine at low-to-medium altitudes, its weaknesses in performance were truly exposed as the engine ran at higher altitudes where Axis fighters and bombers tended to fly. To make matters worse, issues with engine knocking, especially at altitude, plagued these engines and led to a fair few failures. Between the critical altitudes of 20,000 and 30,000 feet (6,096 to 9,144 m), some pilots even described the V-1710 as an absolute pig. Against German Messerschmitts and Japanese Zeroes, this was not even slightly good news. In extreme cases, a P-38's turbo-supercharger would even freeze up in frigid temperatures at high altitudes.

Maintaining the proper lean vs. rich fuel mixture inside the V-1710 gave countless aviation mechanics fits during the war, in the days before fuel injection was commonplace in aero engines. In early adaptations of the P-51 Mustang, the fighter designed when the British War Office asked North American Aviation to build a better, faster Curtiss P-40, the V-1710's limitations became truly unacceptable. These inadequacies were helped somewhat with the V-1710-45 in 1943, which used a small auxiliary supercharger to boost engine performance at altitude, but even this wasn't enough to fully compensate. Soon after the Mustang's deployment to Europe, it was decided the upcoming P-51B (Mustang III in RAF service), would be fitted with Packard Merlin engines the same as the British Spitfire, but built by Packard in Detroit, Michigan.

Still, V-1710s engines did find their way onto upgraded and experimental variants of Second World War fighters like the P-63 Kingcobra and the P-82 Twin Mustang by the war's end. Some of these planes, like the P-82, would go on to serve in the Korean War mounted with V-1710s, as Packard ceased production of the much-preferred, license-built Merlin after World War II. In the end, all 69,305 Allison V-1710s were built at Allison's production facility just a stone's throw away from the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Speaking of auto racing, the V-1710 had a renaissance in the sport soon after its front-line military aviation days were over.

As metric you-know-what-tons of V-1710 V12s entered the surplus civilian aircraft market in the 1950s, it didn't take long for hot rodders in the automotive and power boat spheres to take notice. From land speed record racers to speed boats in the unlimited hydroplane class and monstrous tractor pullers, the emerging American tuner culture of the 1950s fell head over heels in love with the V-1710. Among the people most enthralled was the iconic land speed record driver Art Afrons. Together with his brother Walt, the two would use a V-1710 in their Green Monster land speed record car before transitioning to turbojet engines in later variants.

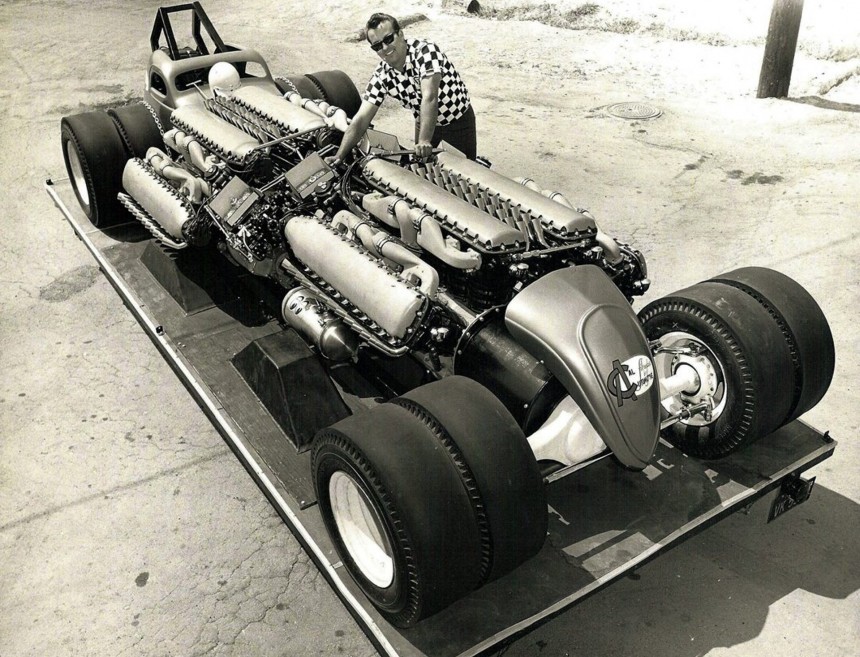

Conversely, drag racing icon Jim Lytle's V-1710-swapped 1932 Ford Coupe became one of the most iconic drag cars of the early 60s not just because of its engine but also its chopped roofline so low that Lytle could stick his head out of the top through a hole in the roof. His creation wound up running a 9.31-second quarter mile at 163 mph (262.3 kph). Lyttle even built a monstrous quad-engine dragster with a single V-1710 powering each axle and named it Quad Al. Al had every intention of racing the thing and making mince meat of other racers, but it never advanced beyond the mockup stage.

Even so, Quad Al remains the most famous V-1710 application in an automotive setting. Does the comparison between a V-1710 and a muscle car engine make more sense now? Today, the V-1710 has come full circle and advanced back to the world of aviation as the go-to engine for vintage warbirds whose original engine cannot easily be obtained. From Russian IL-2 Sturmoviks to German Focke Wulf Fw-190s, these engine swaps ensure the V-1710 will stay a relevant aero engine far into the future. Now, how's that for a wacky story? Heck, maybe we'll delve further into the nutty cars and watercraft that sported V-1710s one day, be on the lookout for it soon.

The V-1710's story is one that's routinely overlooked in favor of the later, more powerful Rolls-Royce/Packard Merlin V12. But in so many ways, the V-1710 was an engine that could have only been built in America. To understand the roots of Allison's most famous engine, we need to go back to well before World War II, to a time when the United States was still trying to prove itself to other aircraft-producing nations of Europe despite being the first to put men in the air. In the time before the proverbial Pax Americana after the two World Wars, such conditions were often the case. Around this time, the company's founder, James A. Allison, made most of his business through the precision manufacturing of race car components at his workshop a short distance away from the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in Speedway, Indiana.

Allison even maintained a shop on Speedway grounds for a time, and his racing hardware became a mainstay at early runnings of the Indy 500 before Europe's great powers decided to boogaloo in 1914. During World War I, the company was instrumental in the development of the Liberty V12 aero engine that, while innovative for the time and the first American liquid-cooled aero engine built during wartime, found itself obsolete soon after the Armistice of 1918. Allison's bespoke production run of inverted L-12s, the VG-1410, was among the first to adopt early adaptations of geared superchargers in the very late1910s.

Soon after the Liberty L-12 grew obsolete in the mid-to-late 20s, the hunt was on to build the next generation of bonkers, high-output American aero engines to define the United States on the global aeronautical stage through the U.S. Army's "Hyper Engine" program. At first, Allison's manager, Norman Gilman, started work on a particularly ridiculous air-cooled, 24-cylinder engine arranged in an X-formation and called the X-4250. When the proposal for this design reached the Army's desk and made their collective brains melt, Allison promptly went back to the drawing board in search of a more conventional design.

From the rib of Allison's concept airship engine, components like the cylinders, single-overhead camshaft, and ethylene glycol liquid cooling system gave unmistakable qualities to the V-1710 V12. If the Liberty L-12 was a giant engine with limited horsepower potential, the V-1710 used the lessons learned over a decade of innovation to build an even larger motor, much more suited to delivering high horsepower figures as the U.S. Army Air Corps and Navy demanded. With 12 cylinders arranged at 65 degrees and a displacement of 1,710.6 cu in (28.032 L), the V-1710 was among the first aeronautical engines to crack the magic 1000-horsepower boundary behind the bonkers Napier Cub X-16 of Great Britain.

Like a performance crate engine in a modern restomod, the V-1710 was designed around a modular platform. Wherein a basic power section with a core nucleus of engine components assembled around the block could be altered with secondary hardware like forced induction to squeeze even more performance out of the design. With the blueprints now set in stone and a small initial production run complete, the V-1710 made its first trip into the air on December 14th, 1936, under the hood of a Consolidated XA-11A mono-wing fighter. Before long, the V-1710 was marked as the standard-issue liquid-cooled inline engine for America's emerging breed of advanced piston fighters.

From the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk to the Lockheed P-38 Lightning twin-engine fighter and even the mid-engined Bell P-39 Airacobra, all utilized Allison V-1710s in various configurations during the Second World War. Thanks to the platform's modular design, adapting the V-1710 to accommodate novel forms of forced induction was relatively easy. To the point that both the original XP-38 and later serial P-38 models flew with sophisticated General Electric B-5 turbo-superchargers, which used both a geared connection to the engine as well as residual exhaust gasses as a means of forced induction. The V-1710 was even trialed on the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress quad-engine bomber for a time to test the platform's adaptability with powertrains other than the standard Wright R-1820 nine-cylinder radials.

Maintaining the proper lean vs. rich fuel mixture inside the V-1710 gave countless aviation mechanics fits during the war, in the days before fuel injection was commonplace in aero engines. In early adaptations of the P-51 Mustang, the fighter designed when the British War Office asked North American Aviation to build a better, faster Curtiss P-40, the V-1710's limitations became truly unacceptable. These inadequacies were helped somewhat with the V-1710-45 in 1943, which used a small auxiliary supercharger to boost engine performance at altitude, but even this wasn't enough to fully compensate. Soon after the Mustang's deployment to Europe, it was decided the upcoming P-51B (Mustang III in RAF service), would be fitted with Packard Merlin engines the same as the British Spitfire, but built by Packard in Detroit, Michigan.

Still, V-1710s engines did find their way onto upgraded and experimental variants of Second World War fighters like the P-63 Kingcobra and the P-82 Twin Mustang by the war's end. Some of these planes, like the P-82, would go on to serve in the Korean War mounted with V-1710s, as Packard ceased production of the much-preferred, license-built Merlin after World War II. In the end, all 69,305 Allison V-1710s were built at Allison's production facility just a stone's throw away from the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Speaking of auto racing, the V-1710 had a renaissance in the sport soon after its front-line military aviation days were over.

As metric you-know-what-tons of V-1710 V12s entered the surplus civilian aircraft market in the 1950s, it didn't take long for hot rodders in the automotive and power boat spheres to take notice. From land speed record racers to speed boats in the unlimited hydroplane class and monstrous tractor pullers, the emerging American tuner culture of the 1950s fell head over heels in love with the V-1710. Among the people most enthralled was the iconic land speed record driver Art Afrons. Together with his brother Walt, the two would use a V-1710 in their Green Monster land speed record car before transitioning to turbojet engines in later variants.

Even so, Quad Al remains the most famous V-1710 application in an automotive setting. Does the comparison between a V-1710 and a muscle car engine make more sense now? Today, the V-1710 has come full circle and advanced back to the world of aviation as the go-to engine for vintage warbirds whose original engine cannot easily be obtained. From Russian IL-2 Sturmoviks to German Focke Wulf Fw-190s, these engine swaps ensure the V-1710 will stay a relevant aero engine far into the future. Now, how's that for a wacky story? Heck, maybe we'll delve further into the nutty cars and watercraft that sported V-1710s one day, be on the lookout for it soon.