Any comparison that is not apples to apples will fundamentally raise questions about fairness. This principle dictates that you can only compare things that are minimally similar for the whole thing to be valid. A recent SAE paper makes it pretty evident that putting ICE cars and electric vehicles side by side when it relates to the range is so complex that we may have to give up on that: it is not an apples-to-apples deal.

The paper uses Car and Driver's 75 mph (121 kph) tests, and there is a good explanation for that. One of the co-authors is Dave VanderWerp, the magazine's testing director. He is also the author of the first story that explained why Tesla EPA numbers were difficult to match in real-life use. The BEV maker follows an optional five-cycle test that gives anyone who adopts it better official numbers than if they followed the standard two-cycle test most other automakers perform. For the record, any car company can use the more extended testing standard: it all depends on the strategy they want to follow: overpromise and underdeliver or underpromise and overdeliver.

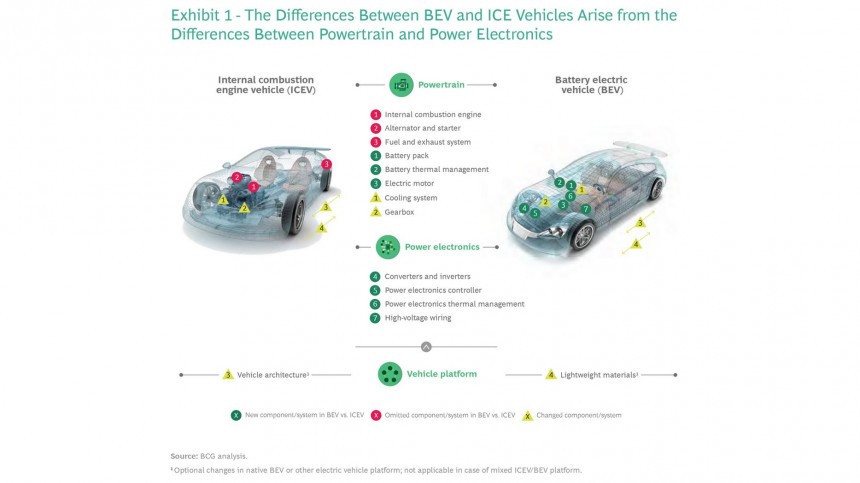

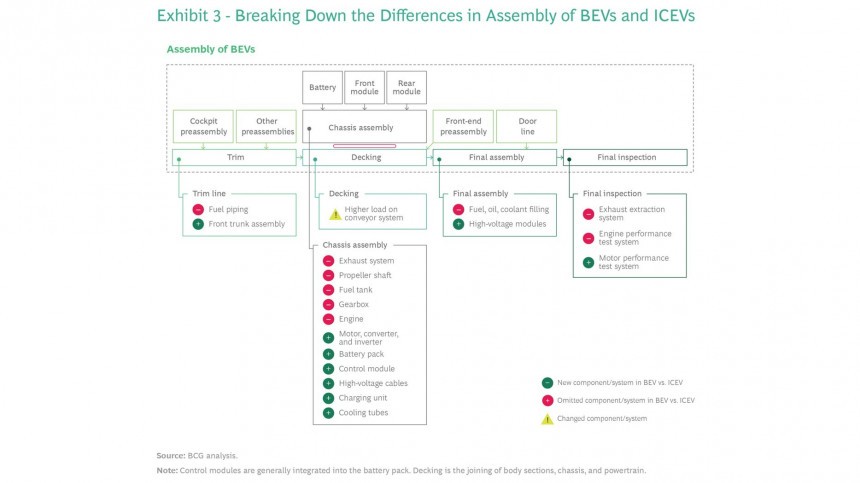

The paper intends to bring EPA numbers closer to reality, but how can you do that when the reality of electric cars and ICE vehicles is so different? The document itself reminds us of their discrepancies. They are so fundamental that they make it challenging – perhaps even impossible – to include them under the same umbrella.

The first one is that any vehicle powered by an internal combustion engine will be more frugal at a constant rpm, usually the one closer to its maximum torque engine speed. This is why fuel consumption drops at highway speeds and is higher in urban cycles. EPA tests have speed variations, with frequent braking and acceleration to simulate rush-hour conditions.

Electric cars present the opposite behavior: they perform better in the city, where the lower speeds do not put them to fight the air as much as they would have to if traveling on highways. The second major difference between them is that regenerative braking can stretch the range of electric cars. It harvests energy that would be lost as heat in ICE cars while they brake several times in traffic. What is a handicap for combustion-engined vehicles in EPA's tests is an edge for BEVs.

Until this point, it may seem electric cars get all the advantages, but that's not so. The third crucial difference between them and ICE vehicles is how efficient a motor is compared to a combustion engine. While that may look like a benefit, it is a feasibility requirement: battery packs cannot hold that much energy. If electric motors wasted as much energy as combustion engines do, no current battery technology would make BEVs work.

A good example comes from Jason Fenske. The Engineering Explained host made a 1,963-mile (3,159 km) road trip spending 560 kWh with his Model 3. That's the energy 16.6 gallons of gasoline contain. It was as if a 1988 BMW 3 Series ran 1,963 miles with a topped-up tank. The bad news is that Fenske's Model 3 had a battery pack that held only the equivalent of around 2 gallons of gas in energy, which theoretically would have forced him to stop eight times to charge. He actually needed to visit charging stations 12 times. How does that harm BEVs? They have no fat to burn.

Generally speaking, combustion engines throw out the window 80% of the chemical energy of fuels as heat – the most efficient mills reduce that to 60%. When an ICE vehicle needs heating, it can extract it from what it wastes, and that will not interfere that much with its range. In a BEV, all heating demands have to come from the same battery pack that also feeds the motors. That will drastically reduce the range in cold weather. At high speeds, an ICE vehicle still has plenty of energy in the fuel tank to ignore aerodynamic deficiencies. In a BEV, fighting the airflow will have a direct impact on how far the vehicle will be able to travel.

These fundamental differences imply that the range of a combustion-engined vehicle increases if it is driven on highways and drops when it remains in the city. Electric cars drive further on urban paths and have much less range on highways. How can you treat such divergent machines with the same testing standards in a fair way?

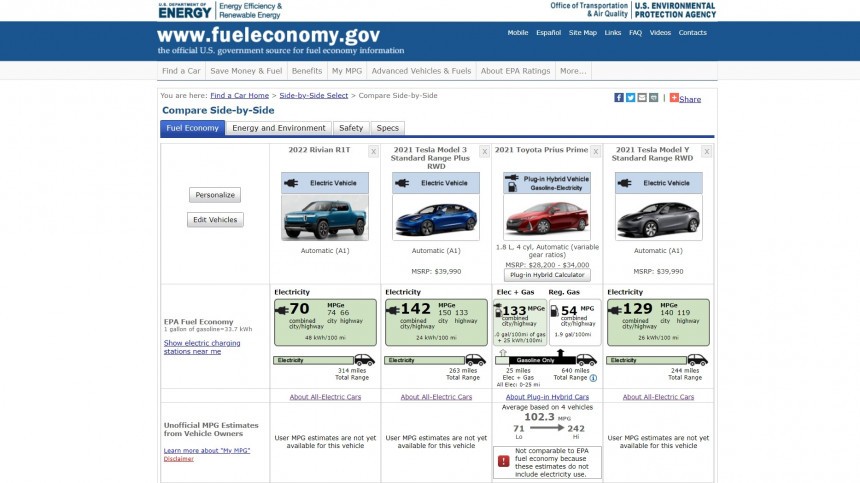

The SAE paper reminds us that the environmental agency only discloses a combined rating, with a 55% prevalence of the urban results. EPA probably does that because people usually drive through city streets most of the time and only occasionally hit a highway to travel long distances. By privileging a condition in which electric cars do better, the agency ends up suggesting BEVs present a better range than they actually do in situations in which that is not even that important.

Just think about it: how many people need to drive 300 miles a day in the city? Apart from delivery teams, no one does that. Electric car owners get back home and put their vehicles to charge. The range only becomes crucial when you need to make a road trip and want to be sure you'll get there. That's when the rosy numbers EPA presents become a burden.

According to the paper, ICE vehicles present 4% better fuel economy on average in the tests Car and Driver made than they scored in EPA tests. When it comes to BEVs, the ranges are, on average, 12.5% worse. Knowing that Tesla and Polestar follow the five-cycle test procedure, I have tried to find all Car and Driver's 75 mph test results for BEVs to measure the impact these vehicles had on the average. The closest to this complete list I got was a story published in April 2021 and updated in August 2022.

Surprisingly, several BEVs present worse numbers than the -12.5% average the paper mentions. In a list with 33 tests, only eight show better results than that figure, and only three exceed it. The worst one is the Hyundai Kona Electric, with a range that is 38% inferior to the already appalling average for BEVs that the SAE paper disclosed.

The paper discussed a concerning issue and made two recommendations to solve it. The first is that EPA discloses both range numbers: one for highway and one for city cycles. The second is that EPA adopts a single testing standard, one that submits all vehicles to the same conditions instead of offering the optional five-cycle procedure. Although that seems like a logical step to compare apples to apples, can that apply to apples and blackberries? How can you test the same way machines that are so intrinsically different? SAE members may consider that a worthy challenge.

The paper intends to bring EPA numbers closer to reality, but how can you do that when the reality of electric cars and ICE vehicles is so different? The document itself reminds us of their discrepancies. They are so fundamental that they make it challenging – perhaps even impossible – to include them under the same umbrella.

Electric cars present the opposite behavior: they perform better in the city, where the lower speeds do not put them to fight the air as much as they would have to if traveling on highways. The second major difference between them is that regenerative braking can stretch the range of electric cars. It harvests energy that would be lost as heat in ICE cars while they brake several times in traffic. What is a handicap for combustion-engined vehicles in EPA's tests is an edge for BEVs.

A good example comes from Jason Fenske. The Engineering Explained host made a 1,963-mile (3,159 km) road trip spending 560 kWh with his Model 3. That's the energy 16.6 gallons of gasoline contain. It was as if a 1988 BMW 3 Series ran 1,963 miles with a topped-up tank. The bad news is that Fenske's Model 3 had a battery pack that held only the equivalent of around 2 gallons of gas in energy, which theoretically would have forced him to stop eight times to charge. He actually needed to visit charging stations 12 times. How does that harm BEVs? They have no fat to burn.

These fundamental differences imply that the range of a combustion-engined vehicle increases if it is driven on highways and drops when it remains in the city. Electric cars drive further on urban paths and have much less range on highways. How can you treat such divergent machines with the same testing standards in a fair way?

Just think about it: how many people need to drive 300 miles a day in the city? Apart from delivery teams, no one does that. Electric car owners get back home and put their vehicles to charge. The range only becomes crucial when you need to make a road trip and want to be sure you'll get there. That's when the rosy numbers EPA presents become a burden.

Surprisingly, several BEVs present worse numbers than the -12.5% average the paper mentions. In a list with 33 tests, only eight show better results than that figure, and only three exceed it. The worst one is the Hyundai Kona Electric, with a range that is 38% inferior to the already appalling average for BEVs that the SAE paper disclosed.