Plutonium is not a fun word to speak, hear, or write. Used to depict an actinide metal we've known about for some time, it has become synonymous with human-caused destruction on a hard-to-comprehend scale.

Plutonium was used to form the cores of the nuclear bombs developed in the U.S. under the Manhattan Project, and later dropped on the Japanese city of Nagasaki (the one dropped on Hiroshima had a uranium core).

That's probably why the word stirs so many negative emotions in people. Yet, as with all other things on this planet, there's nothing innately evil in it, and its maliciousness only comes from how humans choose to use the metal.

You could argue that the "there's nothing innately evil in it" statement is not entirely accurate. After all, plutonium is radioactive. It's most dangerous when inhaled on account of it emitting alpha particles. These get lodged in the lungs and begin killing lung cells, resulting in deadly complications. The stuff can also enter the bloodstream and spread to other organs, causing the same kind of failure.

True, but do remember plutonium can hardly be found on our planet in a natural state, and it is mostly present in our lives as a byproduct of the nuclear power industry. So, again, its maliciousness only comes from how humans choose to use the metal and its derivatives.

Because of their fissile properties (they split and achieve nuclear fission in certain conditions, releasing vast amounts of energy), isotopes the likes of plutonium-239 or plutonium-241 are ideal for use in nuclear bombs. Plutonium-238, on the other hand, is ideal as a power source for, including for spacecraft.

It's exactly this isotope that got NASA all excited this week, thanks to the most recent shipment of the stuff it received from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). It was a large enough quantity (one pound or 0.5 kg) for the space agency to proudly say it was now one step closer to fueling future space missions with it.

Although it may seem small to the rest of us, the quantity DOE produced at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory for NASA's needs is the "largest since the domestic restart of plutonium-238 production over a decade ago."

NASA is using plutonium-238 as a fuel source for the so-called radioisotope power systems, and it has done so for the past 60 years. RPS for short, they are key components in some of the space agency's most high-profile missions ever undertaken (three dozen missions in all), including the Voyager 1 and 2, Cassini-Hyugens, or the still recent Perseverance Martian rover.

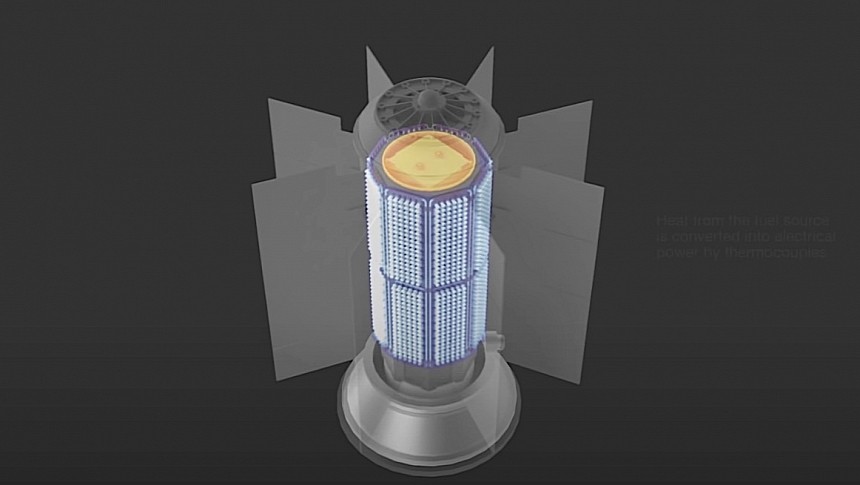

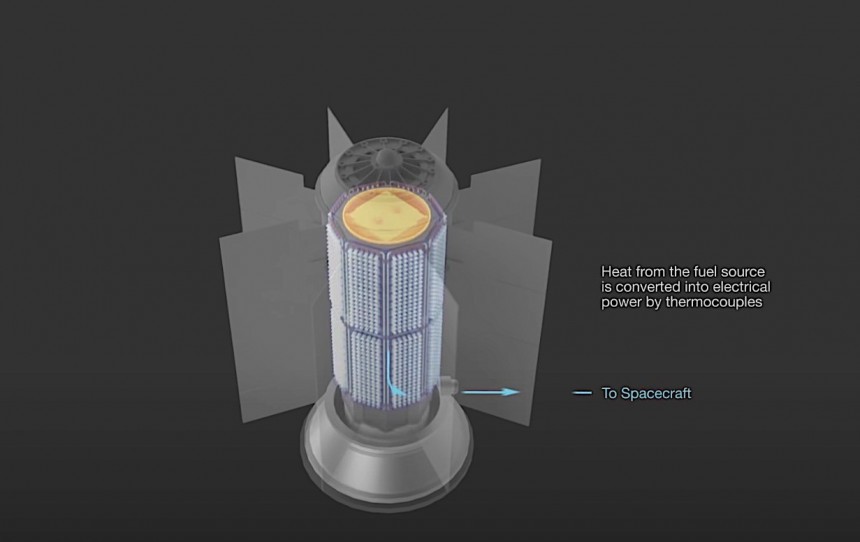

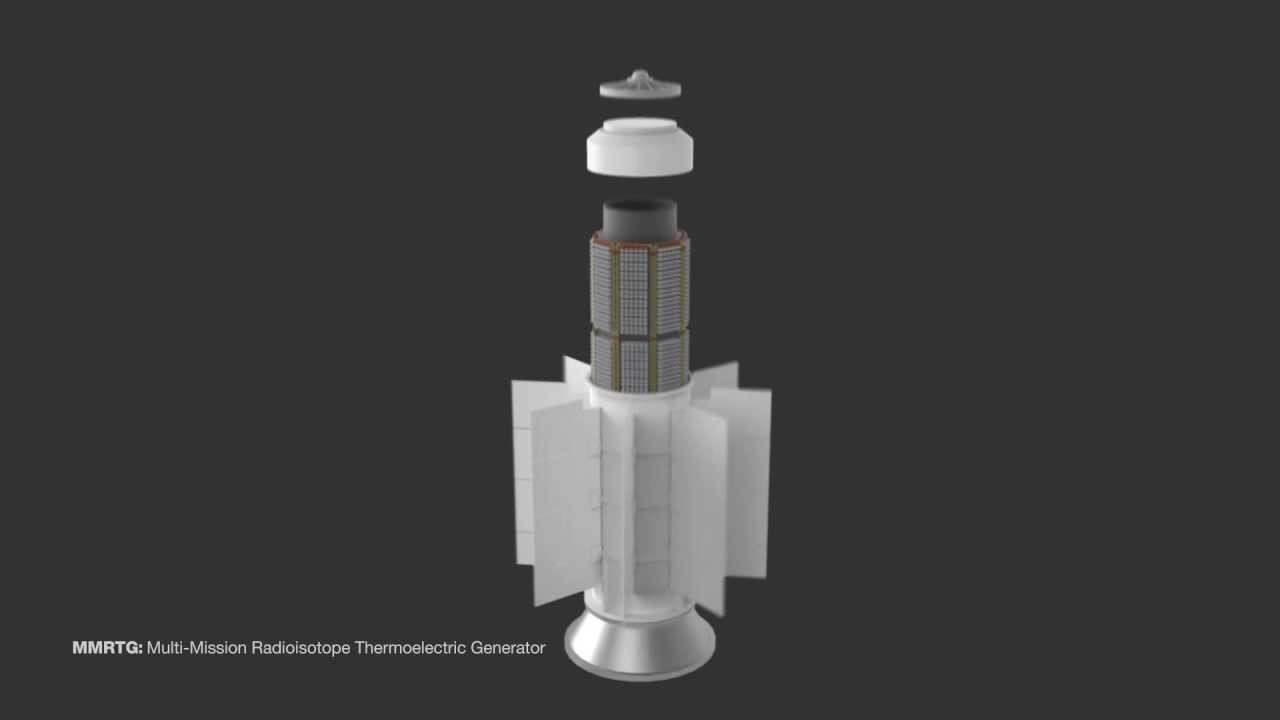

In the rover application, the RPS comes as something called the Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator. MMRTG for short, it's a reactor built by Aerojet Rocketdyne and Teledyne that turns heat from the natural decay of plutonium-238 into electricity.

More precisely 110 watts of the stuff, about as much as a light bulb needs to work here on Earth, but more than enough for the Perseverance to conduct the science missions it was sent to Mars for.

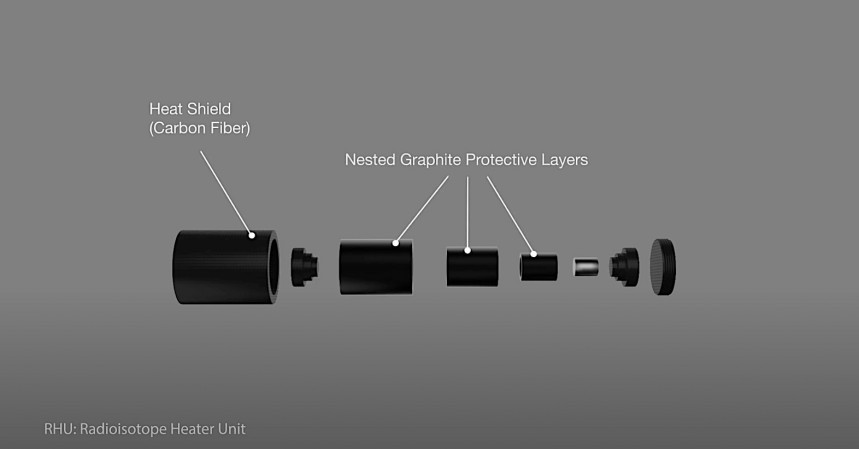

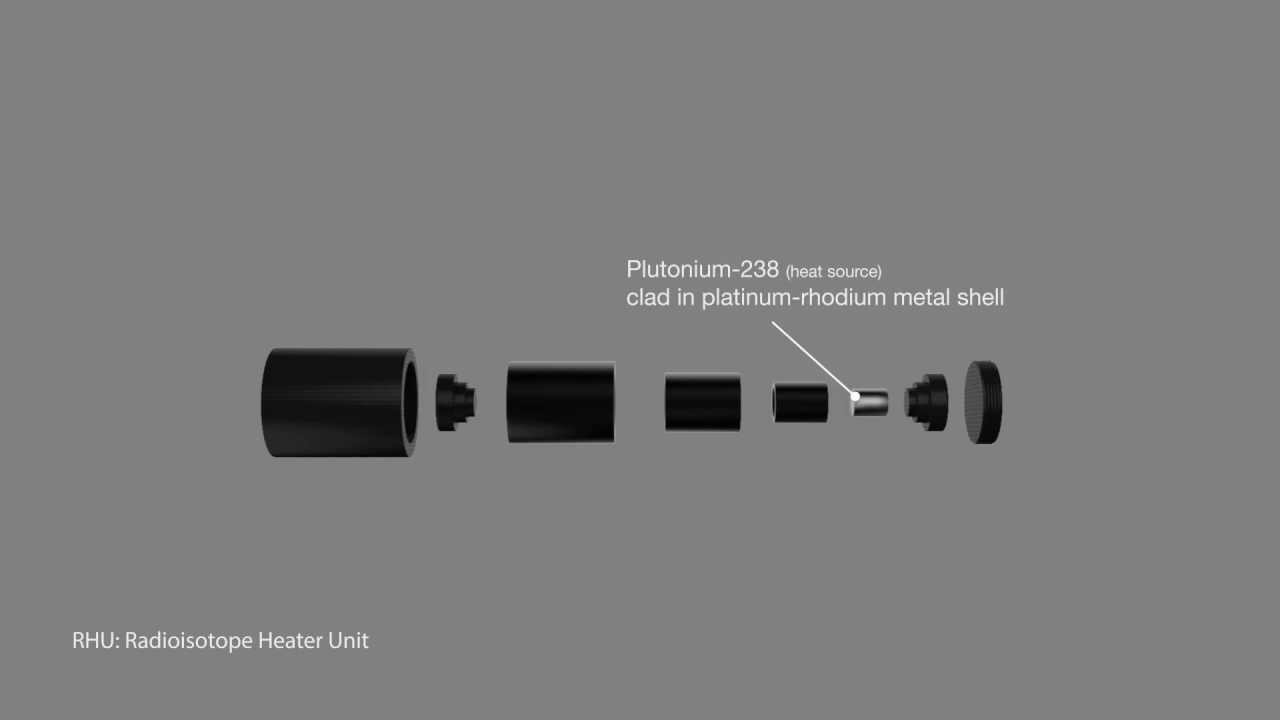

In another application called Light Weight Radioisotope Heater Unit (LWRHU), the radioactive material's decay is transformed into heat. That heat is used to keep the spacecraft components and systems warm enough to be able to do their thing in the cold vastness of space.

Generally speaking NASA tends to use a number of LWRHU on spacecraft, depending on the needs of the mission, size of the spaceship, and so on. For instance, the Apollo 11 mission had two sets of 15 such units, while the Galileo mission relied on no less than 120 of them.

That may seem like a lot, but for reference consider the fact a single LWRHU (which is about the size of a C-cell battery) consists of a single plutonium-238 pellet that outputs about 1 Watts of heat.

The recent delivery of fresh plutonium-238 is seen by NASA as a milestone toward "achieving the constant rate production average target of 1.5 kilograms per year by 2026." The need for more fuel such as this arises from the fact the space agency is planning an increasing number of space missions in the coming years, including the Artemis Moon exploration program and some even bolder attempts at reaching other planets, Mars included.

NASA does not say specifically for what it will use the plutonium it got this week from the DOE, but I'm pretty certain you can bet on these guys not to waste it or put it to harmful use.

Just as a reminder, in 2024 alone NASA has no less than nine missions planned, including the launch of the Intuitive Machines lunar lander, the Europa Clipper, and the Blue Ghost lunar lander.

We'll cover them all in the year ahead, so stay close for more exciting details about humanity's most daring space exploration projects. In the meantime, you can view the two videos below for visual details on the MMRTG and the LWRHU.

That's probably why the word stirs so many negative emotions in people. Yet, as with all other things on this planet, there's nothing innately evil in it, and its maliciousness only comes from how humans choose to use the metal.

You could argue that the "there's nothing innately evil in it" statement is not entirely accurate. After all, plutonium is radioactive. It's most dangerous when inhaled on account of it emitting alpha particles. These get lodged in the lungs and begin killing lung cells, resulting in deadly complications. The stuff can also enter the bloodstream and spread to other organs, causing the same kind of failure.

True, but do remember plutonium can hardly be found on our planet in a natural state, and it is mostly present in our lives as a byproduct of the nuclear power industry. So, again, its maliciousness only comes from how humans choose to use the metal and its derivatives.

Because of their fissile properties (they split and achieve nuclear fission in certain conditions, releasing vast amounts of energy), isotopes the likes of plutonium-239 or plutonium-241 are ideal for use in nuclear bombs. Plutonium-238, on the other hand, is ideal as a power source for, including for spacecraft.

It's exactly this isotope that got NASA all excited this week, thanks to the most recent shipment of the stuff it received from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). It was a large enough quantity (one pound or 0.5 kg) for the space agency to proudly say it was now one step closer to fueling future space missions with it.

NASA is using plutonium-238 as a fuel source for the so-called radioisotope power systems, and it has done so for the past 60 years. RPS for short, they are key components in some of the space agency's most high-profile missions ever undertaken (three dozen missions in all), including the Voyager 1 and 2, Cassini-Hyugens, or the still recent Perseverance Martian rover.

In the rover application, the RPS comes as something called the Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator. MMRTG for short, it's a reactor built by Aerojet Rocketdyne and Teledyne that turns heat from the natural decay of plutonium-238 into electricity.

More precisely 110 watts of the stuff, about as much as a light bulb needs to work here on Earth, but more than enough for the Perseverance to conduct the science missions it was sent to Mars for.

In another application called Light Weight Radioisotope Heater Unit (LWRHU), the radioactive material's decay is transformed into heat. That heat is used to keep the spacecraft components and systems warm enough to be able to do their thing in the cold vastness of space.

Generally speaking NASA tends to use a number of LWRHU on spacecraft, depending on the needs of the mission, size of the spaceship, and so on. For instance, the Apollo 11 mission had two sets of 15 such units, while the Galileo mission relied on no less than 120 of them.

The recent delivery of fresh plutonium-238 is seen by NASA as a milestone toward "achieving the constant rate production average target of 1.5 kilograms per year by 2026." The need for more fuel such as this arises from the fact the space agency is planning an increasing number of space missions in the coming years, including the Artemis Moon exploration program and some even bolder attempts at reaching other planets, Mars included.

NASA does not say specifically for what it will use the plutonium it got this week from the DOE, but I'm pretty certain you can bet on these guys not to waste it or put it to harmful use.

Just as a reminder, in 2024 alone NASA has no less than nine missions planned, including the launch of the Intuitive Machines lunar lander, the Europa Clipper, and the Blue Ghost lunar lander.

We'll cover them all in the year ahead, so stay close for more exciting details about humanity's most daring space exploration projects. In the meantime, you can view the two videos below for visual details on the MMRTG and the LWRHU.