The Moon has no way of escaping the arrival of humans. The Artemis crewed missions scheduled to begin next year are just the tip of the iceberg, the early stages of a planetary-size invasion that will eventually end with the Moon becoming a second home for humanity.

The above is the realization of decades-old dreams by sci-fi writers and visionaries who have always seen the Moon as the perfect staging point for humanity's expansion into the solar system.

The Moon is far from being a suitable place for terraforming, so we'll probably never have large, green open spaces up there, lakes and rivers, and a blue sky. But we will have habitats, road networks, and facilities that will likely be used and served by thousands.

That's a picture from very far in a future whose seeds are already being planted through the many research projects ongoing all over the world. Seeds like something called the PAVER, a possible precursor of future Moon roads building technologies.

PAVER is a project run by a number of European institutions, including Germany's BAM Institute of Materials Research and Testing, Aalen University, Clausthal University of Technology, the German Aerospace Center, and the Austrian Liquifer Systems Group. The project is backed by the European Space Agency (ESA).

PAVER more or less stands for "paving the road for large area sintering of regolith" and its main goal is to turn the lunar surface into something vehicles can drive over. After all, a road network is essential to any civilization, especially nascent ones on other worlds.

But there's more to PAVER than just the need to provide a friendlier running surface for wheeled or tracked machines. Hardening the lunar surface will also act as a barrier against the very damaging lunar dust, perhaps the biggest danger colonizers will ever have to face up there.

The stuff is not the usual, fine grain you find on Earth's beaches. It's sharp and abrasive, it flies everywhere due to the low gravity, and it tends to stick to the stuff it lands on, to the point that during the Apollo missions, it ate away layers upon layers of the astronauts' spacesuits.

Lunar dust is not only dangerous to humans and their garments, but also to machines. During the Apollo 17 mission, for instance, the rover got drowned in the stuff after it lost its rear fender, while the Russian Lunokod 2 completely succumbed after its radiator got clogged with the stuff.

So why not use this same harmful material to make something useful? That's what PAVER proposes, and it plans to use solely sunlight and a clever way to concentrate it.

The idea calls for deploying a Fresnel lens to the Moon to concentrate sunlight and deliver enough melting power to the surface of the satellite. A Fresnel lens is something that was extensively used, for instance, in lighthouses, and it would act more or less as a huge magnifying glass up there.

On the Moon the hardware would have to be a couple of meters (6.5 feet) across to have the desired effect. And by that I mean melt a large enough portion of the lunar surface, and then another, and then another, until a stretch of road, or a landing pad, could be created.

The idea is already being put to the test here Earth, at the Clausthal University of Technology, not by using a Fresnel lens, but a 12-kilowatt carbon dioxide laser meant to simulate concentrated sunlight, fired onto simulated moondust.

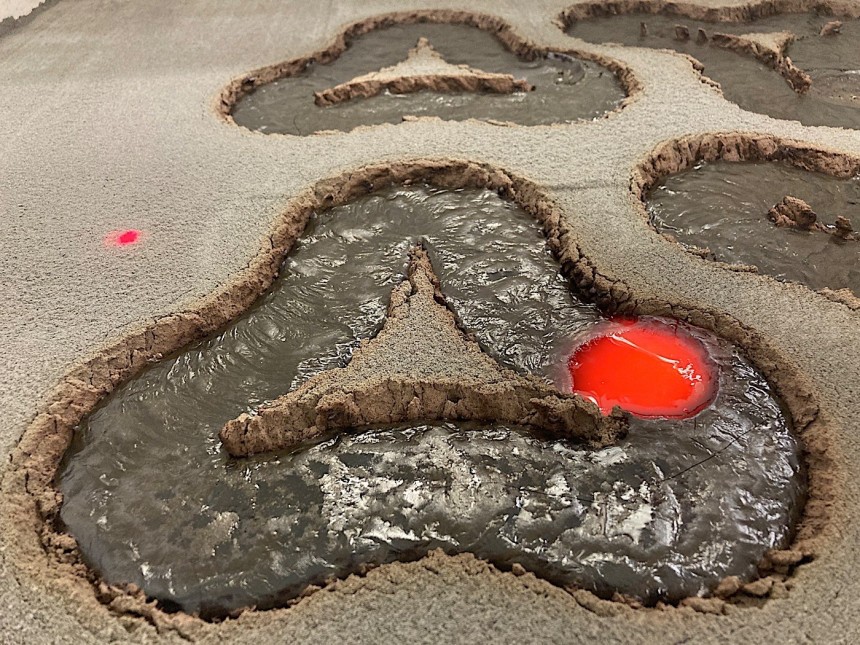

The teams behind the project found that laser beams 4.5 cm (1.8 inches) in diameter and produce molten surfaces in triangular geometric shapes 20 cm (eight inches) across. These shapes could theoretically be interlocked to create larger solid surfaces.

When melted, the lunar soil should turn into a glass-like material. It's not the strongest thing in the world, and it'll probably break quite easily, but it would still be far better than nothing at all.

Also, PAVER people seem to be convinced such surfaces could be easily repaired. Moreover, depending on the exploitation needs of the moment, the melted lunar surface could have various depths, thus becoming more resistant.

The ones working on this idea believe that should a 100 square meters (1,000 square feet) landing pad be required, a Fresnel lens system would be capable of producing it in about 115 days, while providing a two cm deep (0.8-inch) solid surface.

The simple yet at the same time complex workings of such a system are detailed by the team behind the project in a paper published this week in Nature. ESA makes no statement as to whether it sees any actual merit in the tech, but does say it was one of 69 projects that were received as part of a call for ideas for off-world manufacturing and construction.

Can't wait to uncover the rest of them…

The Moon is far from being a suitable place for terraforming, so we'll probably never have large, green open spaces up there, lakes and rivers, and a blue sky. But we will have habitats, road networks, and facilities that will likely be used and served by thousands.

That's a picture from very far in a future whose seeds are already being planted through the many research projects ongoing all over the world. Seeds like something called the PAVER, a possible precursor of future Moon roads building technologies.

PAVER is a project run by a number of European institutions, including Germany's BAM Institute of Materials Research and Testing, Aalen University, Clausthal University of Technology, the German Aerospace Center, and the Austrian Liquifer Systems Group. The project is backed by the European Space Agency (ESA).

PAVER more or less stands for "paving the road for large area sintering of regolith" and its main goal is to turn the lunar surface into something vehicles can drive over. After all, a road network is essential to any civilization, especially nascent ones on other worlds.

But there's more to PAVER than just the need to provide a friendlier running surface for wheeled or tracked machines. Hardening the lunar surface will also act as a barrier against the very damaging lunar dust, perhaps the biggest danger colonizers will ever have to face up there.

Lunar dust is not only dangerous to humans and their garments, but also to machines. During the Apollo 17 mission, for instance, the rover got drowned in the stuff after it lost its rear fender, while the Russian Lunokod 2 completely succumbed after its radiator got clogged with the stuff.

So why not use this same harmful material to make something useful? That's what PAVER proposes, and it plans to use solely sunlight and a clever way to concentrate it.

The idea calls for deploying a Fresnel lens to the Moon to concentrate sunlight and deliver enough melting power to the surface of the satellite. A Fresnel lens is something that was extensively used, for instance, in lighthouses, and it would act more or less as a huge magnifying glass up there.

On the Moon the hardware would have to be a couple of meters (6.5 feet) across to have the desired effect. And by that I mean melt a large enough portion of the lunar surface, and then another, and then another, until a stretch of road, or a landing pad, could be created.

The idea is already being put to the test here Earth, at the Clausthal University of Technology, not by using a Fresnel lens, but a 12-kilowatt carbon dioxide laser meant to simulate concentrated sunlight, fired onto simulated moondust.

When melted, the lunar soil should turn into a glass-like material. It's not the strongest thing in the world, and it'll probably break quite easily, but it would still be far better than nothing at all.

Also, PAVER people seem to be convinced such surfaces could be easily repaired. Moreover, depending on the exploitation needs of the moment, the melted lunar surface could have various depths, thus becoming more resistant.

The ones working on this idea believe that should a 100 square meters (1,000 square feet) landing pad be required, a Fresnel lens system would be capable of producing it in about 115 days, while providing a two cm deep (0.8-inch) solid surface.

The simple yet at the same time complex workings of such a system are detailed by the team behind the project in a paper published this week in Nature. ESA makes no statement as to whether it sees any actual merit in the tech, but does say it was one of 69 projects that were received as part of a call for ideas for off-world manufacturing and construction.

Can't wait to uncover the rest of them…