It can be genuinely difficult to conceptualize the power trip the US Air Force underwent in the immediate aftermath of World War II. While most of Europe and East Asia busied themselves building back from the ashes of battle, the US, safe from most of the bloodshed, was free to go hog-wild with its military production. The end result was one or two designs for war machines that made sense in the minds of handsomely paid military contractors and the generals who greenlit their ideas and very few besides.

In no other scenario would a design as bat-you-know-what crazy as the Douglas 1211-J bomber even become conceptualized. Few have heard of it, and even fewer have seen the concept art. But as we're about to explain, it's probably for the best that the B-52 Stratofortress was chosen instead. But to understand why a quad turboprop-powered mega bomber with provisions for two parasite jet fighters underneath the wings, we need to understand the kind of people in charge of the Air Force in the decade and change following the fall of the Axis powers.

Generals like Carl A. Spaatz, commander of the American Strategic Air Forces in Europe following D-Day in 1944, Haywood S. Hansell, a key mastermind behind the B-29 Superfortress' deployment to the Pacific Theater, and the leading man behind it all, a man often considered the father of American daylight bombing campaigns, a man called Harold Lee George. Though these bombing raids were far bloodless, just read anything about life as a B-17 pilot, these generals proved vindicated by war's end, with the defeated Nazy Germany and Imperial Japan largely reduced to rubble and cinders. Regardless of the distinction between a necessary act of war or a crime against humanity, the outcome at war's end wasn't up for debate.

High off the sensation of Axis "copium," this group of generals and their understudies pushed an agenda in the Air Force's ranks practically before the ink dried on the Japanese articles of surrender. At the heart of this new post-war aerial doctrine were the principles of bomber supremacy. If the results in Europe and Japan were any form of reference, the notion that a heavily armed bomber would always make it to the target was at the heart of the US Air Force philosophy in the very early Cold War. With or without a fighter escort, the idea that at least one in a squadron of strategic bombers could slug it out on the way to the Soviet Union to drop a single devastating nuclear payload was a hill these generals appeared willing to die on.

These men, as a collective, would go by a sinister nickname in civilian-military circles, cheekily christened the Bomber Mafia. But despite the menacing nickname, this group of generals was keen to not involve themselves in more daylight strategic bombing campaigns that disproportionally affected civilians. Efforts to this effect started even before the end of World War II, with inventions like precision bomb sites intended to help bomber crews drop ordinance with far more precision, theoretically sparing non-military collateral damage.

But the next generation of post-war American bombers would go even farther. With the advent of newfangled turbine engines, early Cold War American bombers would fly higher, faster, and drop bombs with more precision than their piston-powered forbearers. At least, that was in the best interests of Bomber Mafia members who were interested in avoiding future war crime tribunals. This group also had a vested interest in keeping nuclear bombers out of the hands of the Navy, then dead set on building a new supercarrier capable of launching nuclear-capable jet bombers and dubbed the United States class.

Thus, the next generation of American strategic bombers would soon be at hand. In 1946, the Army Air Corps, not yet renamed to the Air Force, began fielding offers from domestic manufacturers to build supplemental aircraft to accompany the first in a line of American jet bombers like the North American B-45 Tornado, the Boeing B-47 Stratojet, as well as the colossal Convair B-36 Peacemaker jet-piston hybrid.

It was from this competition that the design for the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress, originally conceptualized as a straight-wing airframe with six turboprop engines vis a vis what the Soviet Tu-95 ultimately became. The bomber mafia personally consulted other notable aerospace manufacturers like the Glenn L. Martin Company, makers of the B-26 Marauder from World War II and contributor to the first generation of jet bomber prototypes via the XB-48 and XB-51, and Consolidated Aircraft, later renamed to Convair and responsible for building the B-24 Liberator during World War II and the B-36 Peacemaker and B-58 Hustler bombers after the war.

However, there was one other applicant in the competition who was so often lost to history by the team at the Douglas Aircraft Company of Santa Monica, California. Known mostly for producing the DC-3, the forbearer to all modern American airliners that moonlit as a troop transport, and the SBD Dauntless dive bomber during the war, Douglas transitioned to some of the very earliest American jet aircraft research in the immediate aftermath of the war. Their exploits with the Douglas Douglas XB-43 Jetmaster light bomber that first flew in 1946, Douglas switched gears to a grander scale with the invitation to compete with Boeing and their XB-52.

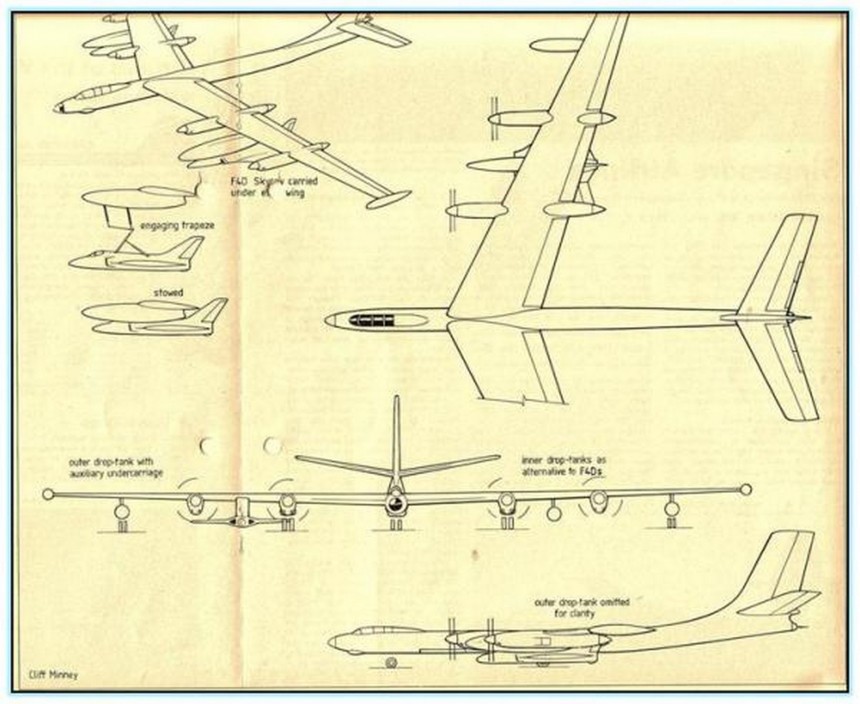

Where Boeing's design, initially dubbed Model 462, started as a straight-wing turboprop strategic bomber before transitioning to a swept-wing turbojet configuration, Douglas opted to skip right to swept wings for better high-altitude performance and increased speed tolerances. Like the original designs for the XB-52, Douglas' new aircraft would employ an unspecified American turboprop engine, possibly the Wright T35, a license-built copy of the Lockheed J37, one of the first domestic American turboprops.

With projected dimensions of 160 and half feet long (48.92 m) and a wingspan of an astounding 227 and a half feet (69.34 m), Douglas' turboprop bomber would've been a touch larger than an XB-52 and weigh a healthy 322,000 lb (146,057 kg) fully loaded with ordinance, that included room for a 43,000 pound conventional bomb on t. Had it flown, what was soon dubbed the Douglass 1211-J would've been among the fastest propeller-driven aircraft ever to fly. Though a modern Tu-95MS with a modern upgrade package can top 575 mph (925 km/h ), the 1211-J would've reached a respectable 520 mph ( 830 km/h).

Considering this prototype would've first flown in the early 1950s at the very latest, the 1211-J would've delivered world-class performance. That said, it's doubtful the 1211-J would've reached that speed with two Douglas F4D Skyray delta-wing fighters originally designed for duties aboard Essex-class aircraft carriers. Before takeoff, mechanics would attach the twin parasite fighters to the 1211-J's underwing pylons and use the combined thrust of each on takeoff tko hoist the gargantuan convoy into the air. In the event of an attack run by enemy fighters, the Skyrays would detach from their pylons and engage the threat with Sidewinder missiles and cannon fire.

In truth, the 1211-J, with its accompaniment of parasite fighters, was a silly idea and one that wasn't even remotely practical. With more powerful turbofan and turbojet engines hitting the scene in between World War II and the Korean War, US aerospace manufacturers, by and large, fully transitioned from propeller-driven bombers and fighters towards full-on jet planes by the end of the 1940s, such was the case for what eventually became the B-52 after at least five design revisions. All the while, the Douglas 1211-J appeared antiquated, outdated, and almost infantile compared to the mighty Stratofortress.

As such, the 1211-J was never even turned into a full-size mockup, let alone an airworthy prototype. But for all its lack of usefulness as a real bomber, you can't help but give props to Douglas for trying something different. That's why it's our pleasure now to showcase it to you almost 80 years after the fact.

Generals like Carl A. Spaatz, commander of the American Strategic Air Forces in Europe following D-Day in 1944, Haywood S. Hansell, a key mastermind behind the B-29 Superfortress' deployment to the Pacific Theater, and the leading man behind it all, a man often considered the father of American daylight bombing campaigns, a man called Harold Lee George. Though these bombing raids were far bloodless, just read anything about life as a B-17 pilot, these generals proved vindicated by war's end, with the defeated Nazy Germany and Imperial Japan largely reduced to rubble and cinders. Regardless of the distinction between a necessary act of war or a crime against humanity, the outcome at war's end wasn't up for debate.

High off the sensation of Axis "copium," this group of generals and their understudies pushed an agenda in the Air Force's ranks practically before the ink dried on the Japanese articles of surrender. At the heart of this new post-war aerial doctrine were the principles of bomber supremacy. If the results in Europe and Japan were any form of reference, the notion that a heavily armed bomber would always make it to the target was at the heart of the US Air Force philosophy in the very early Cold War. With or without a fighter escort, the idea that at least one in a squadron of strategic bombers could slug it out on the way to the Soviet Union to drop a single devastating nuclear payload was a hill these generals appeared willing to die on.

These men, as a collective, would go by a sinister nickname in civilian-military circles, cheekily christened the Bomber Mafia. But despite the menacing nickname, this group of generals was keen to not involve themselves in more daylight strategic bombing campaigns that disproportionally affected civilians. Efforts to this effect started even before the end of World War II, with inventions like precision bomb sites intended to help bomber crews drop ordinance with far more precision, theoretically sparing non-military collateral damage.

Thus, the next generation of American strategic bombers would soon be at hand. In 1946, the Army Air Corps, not yet renamed to the Air Force, began fielding offers from domestic manufacturers to build supplemental aircraft to accompany the first in a line of American jet bombers like the North American B-45 Tornado, the Boeing B-47 Stratojet, as well as the colossal Convair B-36 Peacemaker jet-piston hybrid.

It was from this competition that the design for the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress, originally conceptualized as a straight-wing airframe with six turboprop engines vis a vis what the Soviet Tu-95 ultimately became. The bomber mafia personally consulted other notable aerospace manufacturers like the Glenn L. Martin Company, makers of the B-26 Marauder from World War II and contributor to the first generation of jet bomber prototypes via the XB-48 and XB-51, and Consolidated Aircraft, later renamed to Convair and responsible for building the B-24 Liberator during World War II and the B-36 Peacemaker and B-58 Hustler bombers after the war.

However, there was one other applicant in the competition who was so often lost to history by the team at the Douglas Aircraft Company of Santa Monica, California. Known mostly for producing the DC-3, the forbearer to all modern American airliners that moonlit as a troop transport, and the SBD Dauntless dive bomber during the war, Douglas transitioned to some of the very earliest American jet aircraft research in the immediate aftermath of the war. Their exploits with the Douglas Douglas XB-43 Jetmaster light bomber that first flew in 1946, Douglas switched gears to a grander scale with the invitation to compete with Boeing and their XB-52.

With projected dimensions of 160 and half feet long (48.92 m) and a wingspan of an astounding 227 and a half feet (69.34 m), Douglas' turboprop bomber would've been a touch larger than an XB-52 and weigh a healthy 322,000 lb (146,057 kg) fully loaded with ordinance, that included room for a 43,000 pound conventional bomb on t. Had it flown, what was soon dubbed the Douglass 1211-J would've been among the fastest propeller-driven aircraft ever to fly. Though a modern Tu-95MS with a modern upgrade package can top 575 mph (925 km/h ), the 1211-J would've reached a respectable 520 mph ( 830 km/h).

Considering this prototype would've first flown in the early 1950s at the very latest, the 1211-J would've delivered world-class performance. That said, it's doubtful the 1211-J would've reached that speed with two Douglas F4D Skyray delta-wing fighters originally designed for duties aboard Essex-class aircraft carriers. Before takeoff, mechanics would attach the twin parasite fighters to the 1211-J's underwing pylons and use the combined thrust of each on takeoff tko hoist the gargantuan convoy into the air. In the event of an attack run by enemy fighters, the Skyrays would detach from their pylons and engage the threat with Sidewinder missiles and cannon fire.

In truth, the 1211-J, with its accompaniment of parasite fighters, was a silly idea and one that wasn't even remotely practical. With more powerful turbofan and turbojet engines hitting the scene in between World War II and the Korean War, US aerospace manufacturers, by and large, fully transitioned from propeller-driven bombers and fighters towards full-on jet planes by the end of the 1940s, such was the case for what eventually became the B-52 after at least five design revisions. All the while, the Douglas 1211-J appeared antiquated, outdated, and almost infantile compared to the mighty Stratofortress.