The Lockheed U-2 is a spy plane so exemplary at its job that the US Air Force is still hesitant to get rid of it, even almost 70 years after its first flight. The Dragon Lady, as people often call it, leaves a legacy unlike any other in the history of aviation. But you can't say the same about the ostensible Soviet/Russian equivalent. Almost nobody in the West has even heard of the thing.

This is the low-down on the Myasishchev M-55, the Soviet answer to high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft. Thanks to a grueling Russo-Ukrainian conflict, which both sides appear sick and tired of fighting, the once defunct Russian spy jet might be on the cusp of something practically unheard of. The feat in question is none other than rising from the dead, a return to service after having once been condemned to museums and boneyards. That's right, this no-name recon jet is getting the treatment F-14 Tomcat and Avro Arrow fans could only dream of.

But what gives? Out of all the phenomenal third and fourth-generation fighter jets lost passed to history that could still theoretically be useful in a modern battlefield setting, why the hell is this the one? The answer can't be explained definitively at the moment, with only small tidbits of information leaking out over time from a Russian war machine keen on being tight-lipped with its military operations. But for all the question marks about its tentative potential return to service, the M-55 is a jet that deserves its place in the history of high-altitude spycraft.

To get an idea of what it was like to be a Soviet aeronautical engineer in the late 1970s, it's important to understand the particulars of life behind the Iron Curtain at that time. By this stage in the Cold War, many communist nations in Eastern Europe within the Soviet sphere of influence started to see their once-cozy relationships with the Kremlin begin to sour. From Yugoslavia to Poland and Hungary to Romania, the non-Soviet wing of the Warsaw Pact was eager to air their grievances after being freed from Joseph Stalin's vile grip when the vilest son ever born to a Georgian mother died in 1953.

The Soviets imposed varying degrees of resistance to this regional tension depending on the particulars of each respective nation. Ranging from full-blown political splits from the USSR in the case of Yugoslavia, Albania, and Romania to full-on military violence in Hungary and Czechoslovakia. Whatever the case, the conditions brought on by this perennial chaos in the era of de-Stalinization led to an aerospace sector nowhere near as Soviet-dominant as is often portrayed in the West.

Bespoke national aviation firms in Eastern Bloc nations and individual states in the Soviet Union-proper made for an eclectic group of war vehicles in the armies and air forces of the region. It was a group less homogenously full of MiGs, Sukhois, and Tupolevs than one might expect. In the land that was once the Tsar's Russia, the V. M. Myasishchev Experimental Design Bureau, or simply OKB-23, was one of the smaller Russo-Soviet aviation firms duking it out for Kremlin contracts.

Apart from a Soviet state initiative to build something very similar to Lockheed Skunkworks' U-2, Myasishchev was also responsible for building the M-4 'Molot' supersonic bomber (Russian for Hammer, NATO Codename: Bison) as a rival to the American Boeing B-52 Stratofortress. The firm even had a hand in a couple of Soviet and Russian spaceplane design studies at the tail end of the 20th century. Today, the Myasishchev firm is under the control of the monolithic United Aircraft Corporation, a Russian state-subsidized company set to oversee all domestic military aircraft production on home soil.

But in the late 1970s, Myasishchev's chief initiative was firmly set on high-altitude jet reconnaissance aircraft. The firm certainly didn't have luck on its side; the last Soviet attempt at a U-2 spy plane equivalent, the Beriev S-13, was axed before its first prototype could be completed despite practically being reverse-engineered from a shot-down U-2 in its own right. But Myasishchev's approach was altogether different. Instead of using a single engine like the S-13 and the U-2, what was first christened Subject 34 was designed to employ two smaller jet engines to propel itself.

Forty-five years before the notorious F-22 balloon shootdown incident, Subject 34 was the Soviet solution to identifying American spy balloons at high altitudes before relaying targeting data to ground control for interceptor squadrons to dispatch. Initial blueprints called for Subject 34 to carry two GSh-23 23 mm autocannons with 600 rounds each in dorsal turrets, as if like a strategic bomber. It also called for an unspecified variant of a Soviet air-to-air missile, potentially the R-33, which debuted in 1981. Over time, these additions were omitted in subsequent design phases.

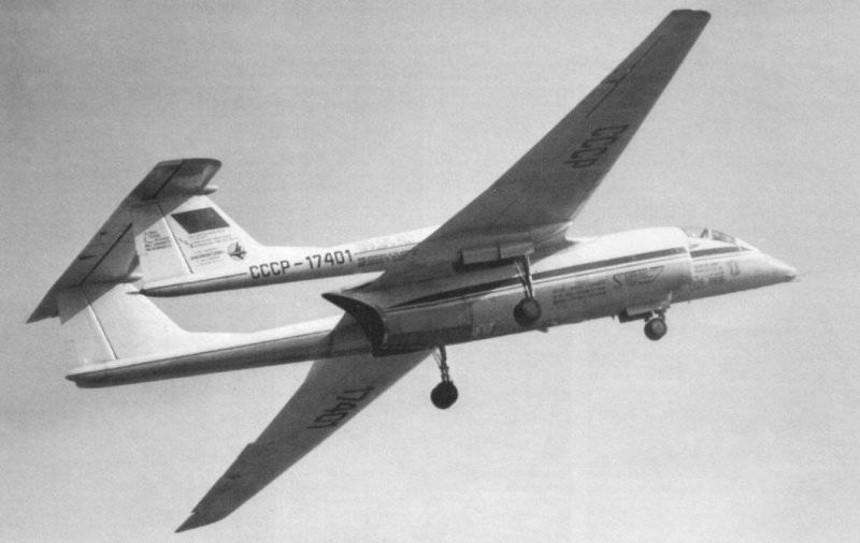

Finally, the single Subject 34 prototype made its maiden flight in December 1978 out of the Kumertau helicopter production plant in Western Russia with test pilot K.V. Chernobrovkin at the stick. He'd later die in a crash during taxi tests when he took off and stalled trying to avoid a snow bank in zero visibility. The aircraft, dubbed Chaika, was destroyed on impact with a hillside. But from the blueprints of Chaika, a production-grade aircraft complete with the same Kolesov RD-36 turbojets as the Tupolev Tu-144 supersonic airliner, was ready to make its first flight on May 26th, 1982.

With dimensions of 24 meters (78.7 ft) and a 40.7-meter (133.5-ft) wingspan, the M-17 Stratosphera was actually slightly larger than the equivalent U-2S of the period with its upgraded General Electric F118 borrowed from the B-2 Spirit. But in the all-important area of maximum operating altitude, the M-17 was nothing short of a force. In its day, the Stratosphera set 12 World Air Sports Federation (FAI), all while reaching a maximum altitude of 21,830 meters (71,620 ft) with Vladimir Arkhipenko at the controls.

From the proverbial rib of the M-17 came an all-new design featuring an even longer fuselage and two Soloviev D-30 low-bypass turbofan engines also found in the Tupolev Tu-134 and Tu-154 airliners as well as the Mikoyan MiG-31 interceptor and the Sukhoi Su-47 prototype fighter, albeit without an afterburner. First flown on August 16th, 1988, the M-55 Geophysica pushed the platform's top speed up to 332 kph (206 mph, 179 kn). With an increased capacity for carrying experimental Earth-science payloads as well as military payloads, the M-55 conducted high-altitude reconnaissance in a wide array of different environments, including the harsh skies over Antarctica.

Even into the very late 1990s, the five M-55s built were flying on the ragged edge of the stratosphere, not too far below the farthest heights an American U-2 can muster. But the aeronautical grim reaper comes to all airframes at some point, meaning the start of the 2000s saw the M-55 go into a state of dormancy in ostensible retirement. But earlier this year, intelligence sourced from the battlefields of Ukraine by the British Ministry of Defense appeared to indicate Russia slated at least one M-55 to come out of retirement in a very nearly unprecedented move by modern military aviation's standards.

How British intelligence gathered this information and the exact nature of Russia's plans for the M-55's tentative mission remain unclear. Although given the circumstances, the prospects of a Russian M-55 Geophysica combing the tundra of a Ukrainian winter spotting for clues to potential movements before another enemy counter-offensive seems to make logical sense. Whatever the case, the notion that a sub-sonic high-altitude spy plane could make a strategic difference in the age of hypersonic cruise missiles and laser-based anti-air defenses might be a tall order by some sensibilities.

For now, the nature of the future of the M-55 is caked in mystery, far more so than any other military aircraft its age. That alone is somewhat remarkable.

But what gives? Out of all the phenomenal third and fourth-generation fighter jets lost passed to history that could still theoretically be useful in a modern battlefield setting, why the hell is this the one? The answer can't be explained definitively at the moment, with only small tidbits of information leaking out over time from a Russian war machine keen on being tight-lipped with its military operations. But for all the question marks about its tentative potential return to service, the M-55 is a jet that deserves its place in the history of high-altitude spycraft.

To get an idea of what it was like to be a Soviet aeronautical engineer in the late 1970s, it's important to understand the particulars of life behind the Iron Curtain at that time. By this stage in the Cold War, many communist nations in Eastern Europe within the Soviet sphere of influence started to see their once-cozy relationships with the Kremlin begin to sour. From Yugoslavia to Poland and Hungary to Romania, the non-Soviet wing of the Warsaw Pact was eager to air their grievances after being freed from Joseph Stalin's vile grip when the vilest son ever born to a Georgian mother died in 1953.

The Soviets imposed varying degrees of resistance to this regional tension depending on the particulars of each respective nation. Ranging from full-blown political splits from the USSR in the case of Yugoslavia, Albania, and Romania to full-on military violence in Hungary and Czechoslovakia. Whatever the case, the conditions brought on by this perennial chaos in the era of de-Stalinization led to an aerospace sector nowhere near as Soviet-dominant as is often portrayed in the West.

Apart from a Soviet state initiative to build something very similar to Lockheed Skunkworks' U-2, Myasishchev was also responsible for building the M-4 'Molot' supersonic bomber (Russian for Hammer, NATO Codename: Bison) as a rival to the American Boeing B-52 Stratofortress. The firm even had a hand in a couple of Soviet and Russian spaceplane design studies at the tail end of the 20th century. Today, the Myasishchev firm is under the control of the monolithic United Aircraft Corporation, a Russian state-subsidized company set to oversee all domestic military aircraft production on home soil.

But in the late 1970s, Myasishchev's chief initiative was firmly set on high-altitude jet reconnaissance aircraft. The firm certainly didn't have luck on its side; the last Soviet attempt at a U-2 spy plane equivalent, the Beriev S-13, was axed before its first prototype could be completed despite practically being reverse-engineered from a shot-down U-2 in its own right. But Myasishchev's approach was altogether different. Instead of using a single engine like the S-13 and the U-2, what was first christened Subject 34 was designed to employ two smaller jet engines to propel itself.

Forty-five years before the notorious F-22 balloon shootdown incident, Subject 34 was the Soviet solution to identifying American spy balloons at high altitudes before relaying targeting data to ground control for interceptor squadrons to dispatch. Initial blueprints called for Subject 34 to carry two GSh-23 23 mm autocannons with 600 rounds each in dorsal turrets, as if like a strategic bomber. It also called for an unspecified variant of a Soviet air-to-air missile, potentially the R-33, which debuted in 1981. Over time, these additions were omitted in subsequent design phases.

With dimensions of 24 meters (78.7 ft) and a 40.7-meter (133.5-ft) wingspan, the M-17 Stratosphera was actually slightly larger than the equivalent U-2S of the period with its upgraded General Electric F118 borrowed from the B-2 Spirit. But in the all-important area of maximum operating altitude, the M-17 was nothing short of a force. In its day, the Stratosphera set 12 World Air Sports Federation (FAI), all while reaching a maximum altitude of 21,830 meters (71,620 ft) with Vladimir Arkhipenko at the controls.

From the proverbial rib of the M-17 came an all-new design featuring an even longer fuselage and two Soloviev D-30 low-bypass turbofan engines also found in the Tupolev Tu-134 and Tu-154 airliners as well as the Mikoyan MiG-31 interceptor and the Sukhoi Su-47 prototype fighter, albeit without an afterburner. First flown on August 16th, 1988, the M-55 Geophysica pushed the platform's top speed up to 332 kph (206 mph, 179 kn). With an increased capacity for carrying experimental Earth-science payloads as well as military payloads, the M-55 conducted high-altitude reconnaissance in a wide array of different environments, including the harsh skies over Antarctica.

Even into the very late 1990s, the five M-55s built were flying on the ragged edge of the stratosphere, not too far below the farthest heights an American U-2 can muster. But the aeronautical grim reaper comes to all airframes at some point, meaning the start of the 2000s saw the M-55 go into a state of dormancy in ostensible retirement. But earlier this year, intelligence sourced from the battlefields of Ukraine by the British Ministry of Defense appeared to indicate Russia slated at least one M-55 to come out of retirement in a very nearly unprecedented move by modern military aviation's standards.

For now, the nature of the future of the M-55 is caked in mystery, far more so than any other military aircraft its age. That alone is somewhat remarkable.