To win a World War, you can't start without a foundation of excellent engines. History teaches us this many times over. Be it with the Liberty V12 in World War I or the Rolls-Royce Merlin of World War II. No great warplane is complete without one. But oftentimes, one of these great names finds itself perpetually snubbed by more famous models.

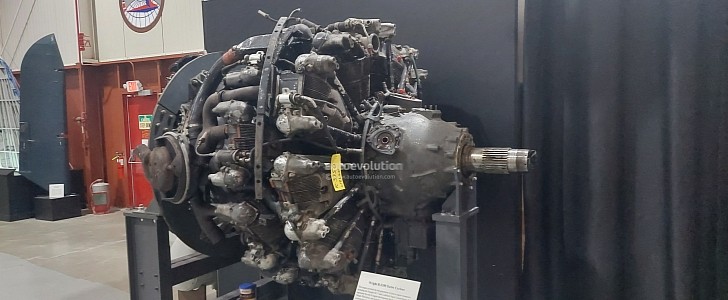

The Wright R-3350 is a classic case in point. Though it was larger, more powerful, and more capable than a Merlin, or even the Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp, the Duplex-Cyclone, as it was known, doesn't carry even half of the name recognition as the more famous World War II piston engines. Though it must be said, the Duplex-Clone was first run several years before America's entry into the war, back in 1937.

It was in preparation to fly with an experimental super-heavy bomber that even many in wargaming and war history circles have never heard of it before. It's easy to get the wrong impression of the single Douglas XB-19 ever made. Apart from being utterly colossal with a 212-foot (64.6 m) wingspan, it was also the operational debut of the venerable Duplex-Cyclone. Though other aspects of its design, like lack of speed or maneuverability, plagued the XB-19 program, the one positive point USAAF pilots all raved about was its Wright R-3350 engines.

These radial engines with two rows of nine cylinders on offer and sharing a common prop-shaft measured in a massive 3,350 cubic inches (54.9 L). In general, radial, or reciprocating engines, as they used to be called, acted a role a bit like semi-truck diesel engines in the sky. Gargantuan, relatively powerful low RPMs and often supremely reliable machines that used turbulent air at high speeds needed for the sustained flight to cool themselves instead of liquid coolant.

Every molecule of the Duplex-Cyclone's construction was forged with the finest components the American war machine had at its disposal. It was honed in to be more reliable and powerful as WWII progressed through the crucible of combat. Early models of the 3350 used carburetors.

Yet the problems with fuel/air ratios at altitude this caused, further muddled by issues with the supercharger, prompted Wright to switch to a very early version of gasoline direct-injection (GDI), a technology the automotive wouldn't utilize fully until five or six decades later.

With an estimated total power output exceeding 2,000 horsepower, it was possible for aircraft of any size equipped with this engine to haul many times as much cargo or ordinance as airframes with other, lesser engines. It's said the single-engined Douglas A-1 Skyraider Cold War attacker could carry a bigger payload than a quad-engined Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress of WWII vintage for this reason. A single-stage, two-speed supercharger ensured the Duplex-Cyclone could handle heavy load demands even at exceedingly higher and higher altitudes.

Because of the high magnesium content in the crankcases of early Duplex-Cyclones, there was always a lingering danger that any engine fire could spiral out of control as the highly reactive metal under extreme heat fanned the flames to over 5,600°F (3,100 °C). For some context, Space Shuttle heat titles only needed to shrug off 3000°F (1,648 °C) during atmospheric reentry. In short, such a magnesium-fueled engine fire would've ripped the wings off any airplane it was attached to.

Once most of the issues were fixed as the development of the engine continued, the result was nothing short of spectacular. Everything from the B-29 Superfortresses that dropped both atomic weapons over Japan to colossal Martin JRM Mars super heavy seaplane, the Douglas A-1 Skyraider attack aircraft, and the iconic Douglas DC-7 and Lockheed Constellation post-war airliners all made use of the Duplex-Cyclone among a list of airframes over 30 names long.

Furthermore, the engine became a fixture of civilian air racing later in life, powering Rare Bare, a modified Grumman F8F Bearcat named Rare Bear, to a record-breaking speed of 528.33 mph (850.26 km/h) set on August 21, 1989, a record in the three-kilometer sprint category that still stands to this day for piston-engined airplanes. As many as 40,000 Wright 3350 Duplex-Cyclone engines were built at Wright Aeronautical's factories in both Cincinnati, Ohio, and Woodbridge, New Jersey, respectively.

Today, this example is displayed at the Glenn H Curtiss Museum in Hammondsport, New York, a facility dedicated to the man whose company would one day go on to work with Wright to play a pivotal role in the Duplex-Cyclone's development. We end by saying this, you can't fully comprehend how massive this engine is until it's towering over you in the flesh.

Check out some of our other pieces from our trip to the Glenn H Curtiss Museum right here on autoevolution.

It was in preparation to fly with an experimental super-heavy bomber that even many in wargaming and war history circles have never heard of it before. It's easy to get the wrong impression of the single Douglas XB-19 ever made. Apart from being utterly colossal with a 212-foot (64.6 m) wingspan, it was also the operational debut of the venerable Duplex-Cyclone. Though other aspects of its design, like lack of speed or maneuverability, plagued the XB-19 program, the one positive point USAAF pilots all raved about was its Wright R-3350 engines.

These radial engines with two rows of nine cylinders on offer and sharing a common prop-shaft measured in a massive 3,350 cubic inches (54.9 L). In general, radial, or reciprocating engines, as they used to be called, acted a role a bit like semi-truck diesel engines in the sky. Gargantuan, relatively powerful low RPMs and often supremely reliable machines that used turbulent air at high speeds needed for the sustained flight to cool themselves instead of liquid coolant.

Every molecule of the Duplex-Cyclone's construction was forged with the finest components the American war machine had at its disposal. It was honed in to be more reliable and powerful as WWII progressed through the crucible of combat. Early models of the 3350 used carburetors.

With an estimated total power output exceeding 2,000 horsepower, it was possible for aircraft of any size equipped with this engine to haul many times as much cargo or ordinance as airframes with other, lesser engines. It's said the single-engined Douglas A-1 Skyraider Cold War attacker could carry a bigger payload than a quad-engined Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress of WWII vintage for this reason. A single-stage, two-speed supercharger ensured the Duplex-Cyclone could handle heavy load demands even at exceedingly higher and higher altitudes.

Because of the high magnesium content in the crankcases of early Duplex-Cyclones, there was always a lingering danger that any engine fire could spiral out of control as the highly reactive metal under extreme heat fanned the flames to over 5,600°F (3,100 °C). For some context, Space Shuttle heat titles only needed to shrug off 3000°F (1,648 °C) during atmospheric reentry. In short, such a magnesium-fueled engine fire would've ripped the wings off any airplane it was attached to.

Once most of the issues were fixed as the development of the engine continued, the result was nothing short of spectacular. Everything from the B-29 Superfortresses that dropped both atomic weapons over Japan to colossal Martin JRM Mars super heavy seaplane, the Douglas A-1 Skyraider attack aircraft, and the iconic Douglas DC-7 and Lockheed Constellation post-war airliners all made use of the Duplex-Cyclone among a list of airframes over 30 names long.

Today, this example is displayed at the Glenn H Curtiss Museum in Hammondsport, New York, a facility dedicated to the man whose company would one day go on to work with Wright to play a pivotal role in the Duplex-Cyclone's development. We end by saying this, you can't fully comprehend how massive this engine is until it's towering over you in the flesh.

Check out some of our other pieces from our trip to the Glenn H Curtiss Museum right here on autoevolution.