Now that we know there are countless planets spread throughout our galaxy, the race to learn more about them is on. And with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) out there looking at some of them, it’s going to be a very interesting race.

Webb has been up there for more than a year now, using an array of instruments to look at distant places in our galaxy in ways never before possible. And the rate at which it returns incredible science is simply stunning, making the 10 billion dollars spent on its development seem to have been more than worth it.

The latest gimmick from this incredible telescope has to do with a small rocky planet called TRAPPIST-1 b. It is one of seven such balls of rock that orbit an ultracool red dwarf star (they call these things M dwarfs), located some 40 light years away from Earth in a constellation called Aquarius.

That’s a system we’ll probably learn more and more about in the near future, because according to scientists the place is “a great laboratory” if we want to study the “habitability around M stars.”

TRAPPIST-1 b is the innermost planet of the seven, and it’s a little over ten percent larger than our own Earth. It spins around its star at a distance about one hundred times smaller than the one between our planet and the Sun, and it’s tidally locked with its star, meaning one face of it is a burning hell and the other a freezing dark nightmare.

Being so close to the star means the side that always faces the light receives a lot of energy – about four times more than our planet gets from its Sun. And that also means the planet releases a lot of thermal emissions in the form of infrared light.

It is exactly this kind of light Webb was able to spot when looking at TRAPPIST-1 b. It might not seem all that spectacular at first glance, but this is “the first detection of any form of light emitted by an exoplanet as small and as cool as the rocky planets in our own solar system,” according to the team of scientists doing this research.

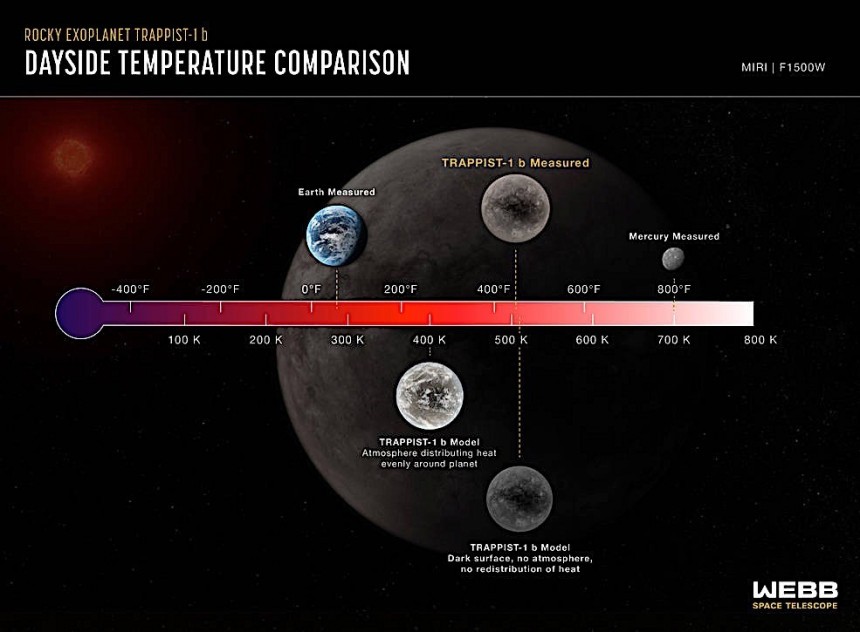

Seeing thermal emissions allowed people to estimate the temperature on the star-facing side of the planet, and according to them, that would be 450 degrees F (232 Celsius). Such a hot environment eliminates the chance of the place having a significant atmosphere and, by extension, being capable of supporting life as we know it.

True, TRAPPIST-1 b is not exactly in its system’s habitable zone, so that kind of was to be expected. What Webb proved though by being able to “measure such dim mid-infrared light” is that it can easily do the same for the other planets spinning around their M dwarfs, but others as well. And that ability should give us a proper sense of planets such as these having atmospheres capable of supporting life.

The latest gimmick from this incredible telescope has to do with a small rocky planet called TRAPPIST-1 b. It is one of seven such balls of rock that orbit an ultracool red dwarf star (they call these things M dwarfs), located some 40 light years away from Earth in a constellation called Aquarius.

That’s a system we’ll probably learn more and more about in the near future, because according to scientists the place is “a great laboratory” if we want to study the “habitability around M stars.”

TRAPPIST-1 b is the innermost planet of the seven, and it’s a little over ten percent larger than our own Earth. It spins around its star at a distance about one hundred times smaller than the one between our planet and the Sun, and it’s tidally locked with its star, meaning one face of it is a burning hell and the other a freezing dark nightmare.

Being so close to the star means the side that always faces the light receives a lot of energy – about four times more than our planet gets from its Sun. And that also means the planet releases a lot of thermal emissions in the form of infrared light.

Seeing thermal emissions allowed people to estimate the temperature on the star-facing side of the planet, and according to them, that would be 450 degrees F (232 Celsius). Such a hot environment eliminates the chance of the place having a significant atmosphere and, by extension, being capable of supporting life as we know it.

True, TRAPPIST-1 b is not exactly in its system’s habitable zone, so that kind of was to be expected. What Webb proved though by being able to “measure such dim mid-infrared light” is that it can easily do the same for the other planets spinning around their M dwarfs, but others as well. And that ability should give us a proper sense of planets such as these having atmospheres capable of supporting life.