Suppose you don't think something as mundane as an airplane can elicit a genuine emotional response. In that case, we recommend you make the trip to the Steven Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia, ASAP.

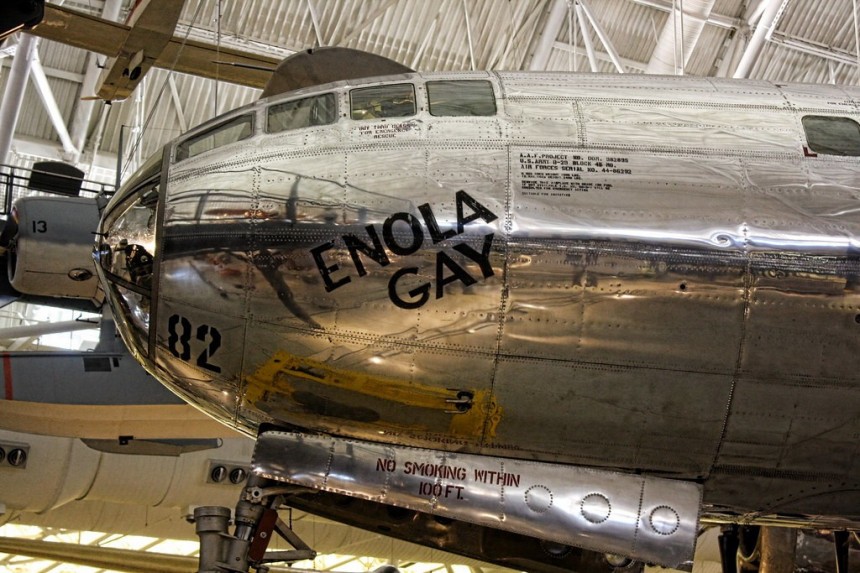

Because on display at this official annex of the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum is a plane that caused more profound amazement and abject horror all at the same time than any other in history. An aircraft that genuinely changed the course of history. Not that it needs any introduction, say hello to Enola Gay. The most controversial single plane in the history of aviation, bar none. On the outside, Enola Gay is a perfectly normal Boeing B-29 Superfortress Strategic Bomber. Don't be fooled, friend. There's a heck of a lot more to the story than that.

Firstly, Enola Gay was not just any Superfortress. It was one of only 65 ever built to the Army Air Force's "Silverplate" designation. These modified bombers were upgraded over standard B-29s to carry nuclear ordinance as its primary mission. Enola Gay was manufactured under license by Glenn. L Martin company, the eventual second half of Lockheed Martin. It rolled off the assembly lie in Omaha, Nebraska, on May 18th, 1945.

Some of its modifications included new pneumatic bomb bay doors and clever British release mechanisms to keep nuclear bombs in place until ready to drop them on target. Allied forces thought that the British Avro Lancaster could be suited for the role of nuclear payload delivery if production on the Superfortress ran into problems.

Ultimately, Enola Gay was selected personally by Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, Commander of the 509th Composite Group, on May 9th, 1945, while it still hadn't touched its landing gears down on the factory floor. He then assigned it to the 383rd Bombardment Squadron, Heavy, 509th Composite Group. After a brief pitstop at Wendover Field in Utah, Enola Gay made the voyage to the Pacific Theater. Landing first in Guam for checks to ensure the bomb bay was ready for its mission.

Meanwhile, the weapon Enola Gay was meant to carry was nearly ready for deployment. The "Little Boy" Uranium Bomb contained a little over 140 (60kg) pounds of radioactive material on board out of almost 10,000 (4,400 kg) pounds of other material. In truth, it only needed a fraction of that to undergo nuclear fission for the bomb to have its intended effect. That being the utter demoralization of the Japanese homeland.

Just before the mission began, Colonel Tibbets christened his Superfortress. Naming it after his mother, Enola Gay Tibbets. At 8:15 p.m. on August 5th, 1945, Enola Gay's Crew released the bomb from its bay doors. Fifty-three seconds later, tens of thousands were vaporized by humanity's violent entry into the Atomic Age. Some 75,000 people died as a direct result of Little Boy's explosion and subsequent radioactive fallout. A great thump hit the aircraft as the shockwave shot across the landscape in all directions.

Otherwise, the crew was totally unharmed. Enola Gay would then serve as a spotter plane for the second Atomic Bombing of Nagasaki. A site chosen after the crew of the Enola confirmed less than ideal cloud conditions at the primary target of Kokura. After the war, it was decided by the United States Army Air Force that the Enola Gay must be preserved. Its title was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution in 1946 and removed from USAAF inventory.

The airframe was stored at several airbases in the continental US until August 10th, 1960. Nearly 15 years to the day after its historic mission. The airframe was disassembled and stored at the official Smithsonian archival facility in Suitland-Silver Hill, Maryland. Enola Gay remained in this state until a former B-52 Stratofortress pilot named Walter J Boyne assumed the position of director of the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum. The new director made its complete restoration a top priority. Over 300,000 hours of labor stood between Boyne and his goal.

The museum initially planned to display Enola Gay's fuselage as a part of the 50th anniversary of the Hiroshima mission in the summer of 1995. Accusations came from a range of reasons and backgrounds. From the exhibit being insensitive to the hundreds of thousands of civilians who died in the attacks and their loved ones, to that it focused too much on the human loss side and not nearly enough on the scientific achievements achieved with the American nuclear program.

The exhibit went on public on the 28th of June, 1995. Three people were arrested for throwing human blood and human ashes onto Enola Gay's aluminum skin. The unfinished project was returned to its restoration hangar, where The fuselage and wings were reunited for the first time in decades on April 10th 2003. Just in time for the opening of the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, where it sits today.

With all this in mind, maybe it's a bit easier to understand why you can't help but get somewhat misty-eyed when you see Enola Gay in the flesh. The museum's series of catwalks give you access to peek right into the cockpit of the Silverplate B-29. It's so easy in one's mind's eye to envision the look of horror, awe, and astonishment as they looked upon destruction on a scale never before seen in the history of mankind.

It's an experience that alone merits a trip to Chantilly to see the plane for yourself. But be warned, be respectful when around Enola Gay. That means no obnoxious selfies with it in the background. This plane means so much to so many people. So you may as well put some respect on the name. Many many thanks to the PR team and floor staff at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center for allowing us to bring you the full story of the most polarizing singular aircraft in human history.

Firstly, Enola Gay was not just any Superfortress. It was one of only 65 ever built to the Army Air Force's "Silverplate" designation. These modified bombers were upgraded over standard B-29s to carry nuclear ordinance as its primary mission. Enola Gay was manufactured under license by Glenn. L Martin company, the eventual second half of Lockheed Martin. It rolled off the assembly lie in Omaha, Nebraska, on May 18th, 1945.

Some of its modifications included new pneumatic bomb bay doors and clever British release mechanisms to keep nuclear bombs in place until ready to drop them on target. Allied forces thought that the British Avro Lancaster could be suited for the role of nuclear payload delivery if production on the Superfortress ran into problems.

Ultimately, Enola Gay was selected personally by Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, Commander of the 509th Composite Group, on May 9th, 1945, while it still hadn't touched its landing gears down on the factory floor. He then assigned it to the 383rd Bombardment Squadron, Heavy, 509th Composite Group. After a brief pitstop at Wendover Field in Utah, Enola Gay made the voyage to the Pacific Theater. Landing first in Guam for checks to ensure the bomb bay was ready for its mission.

Just before the mission began, Colonel Tibbets christened his Superfortress. Naming it after his mother, Enola Gay Tibbets. At 8:15 p.m. on August 5th, 1945, Enola Gay's Crew released the bomb from its bay doors. Fifty-three seconds later, tens of thousands were vaporized by humanity's violent entry into the Atomic Age. Some 75,000 people died as a direct result of Little Boy's explosion and subsequent radioactive fallout. A great thump hit the aircraft as the shockwave shot across the landscape in all directions.

Otherwise, the crew was totally unharmed. Enola Gay would then serve as a spotter plane for the second Atomic Bombing of Nagasaki. A site chosen after the crew of the Enola confirmed less than ideal cloud conditions at the primary target of Kokura. After the war, it was decided by the United States Army Air Force that the Enola Gay must be preserved. Its title was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution in 1946 and removed from USAAF inventory.

The airframe was stored at several airbases in the continental US until August 10th, 1960. Nearly 15 years to the day after its historic mission. The airframe was disassembled and stored at the official Smithsonian archival facility in Suitland-Silver Hill, Maryland. Enola Gay remained in this state until a former B-52 Stratofortress pilot named Walter J Boyne assumed the position of director of the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum. The new director made its complete restoration a top priority. Over 300,000 hours of labor stood between Boyne and his goal.

The exhibit went on public on the 28th of June, 1995. Three people were arrested for throwing human blood and human ashes onto Enola Gay's aluminum skin. The unfinished project was returned to its restoration hangar, where The fuselage and wings were reunited for the first time in decades on April 10th 2003. Just in time for the opening of the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, where it sits today.

With all this in mind, maybe it's a bit easier to understand why you can't help but get somewhat misty-eyed when you see Enola Gay in the flesh. The museum's series of catwalks give you access to peek right into the cockpit of the Silverplate B-29. It's so easy in one's mind's eye to envision the look of horror, awe, and astonishment as they looked upon destruction on a scale never before seen in the history of mankind.

It's an experience that alone merits a trip to Chantilly to see the plane for yourself. But be warned, be respectful when around Enola Gay. That means no obnoxious selfies with it in the background. This plane means so much to so many people. So you may as well put some respect on the name. Many many thanks to the PR team and floor staff at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center for allowing us to bring you the full story of the most polarizing singular aircraft in human history.