Depicted in countless movies and written works of art, micrometeoroid impacts with a living person or the hardware that keeps them alive in space are also an astronaut’s worst nightmare. Unlike any mechanical failure, which with a bit of skill and luck can be fixed, micrometeoroid impacts can not only end space missions, but lives as well.

Technically speaking, a micrometeoroid is a tiny piece of rock that under normal circumstances (like say after passing through Earth’s atmosphere) would pose no danger. The problem is these things are never to be found in normal circumstances, and are known to travel through space at speeds of over 22,000 mph (35,400 kph). At those speeds, and with virtually no way to detect them in time, they’re like cannon shells for anyone or anything standing in their way.

The people that have gone up to the International Space Station (ISS) over the years have gotten used to this ever-present danger, comfortable in the knowledge that the materials the spaceships and their suits are made of can do more than a decent job in protecting them against impacts.

But later this decade we’re going to the Moon, and there’s an entirely new ball game up there. Sure, we’ve been there before, but enough time has passed since to make us both wiser and more cautious.

Artemis is how the new Moon exploration program is called, and everything in it is brand new compared to Apollo, from the spacecraft to the mission and procedures. The astronauts' suits, their habitats, and even their vehicles are new, not only in design, but also in terms of materials as well.

We have the technology here on Earth to test how various materials would resist micrometeoroid impacts, and NASA is not shying away from using it. With the first Artemis launch just around the corner, knowing what works and what doesn’t is essential.

The Glenn Research Center is the place where something called Ballistic Impact Lab resides. That would be a facility that houses a 40-foot-long air gun capable of shooting out one end various projectiles at speeds that can reach 2,000 mph (3,200 kph). Not quite the speed of a meteorite, but given how they shoot steel ball bearings, among other things, the results should come close enough.

A number of textiles and fabrics for Artemis have already been tested by NASA engineers this way, as the race is on to find out things like how many layers would be needed to stop micrometeoroid penetration.

The first series of tests also included materials being considered as building solutions for habitats, which need to be soft and flexible when left alone, but capable of turning very stiff is struck. Kind of like some non-Newtonian fluids, if you like.

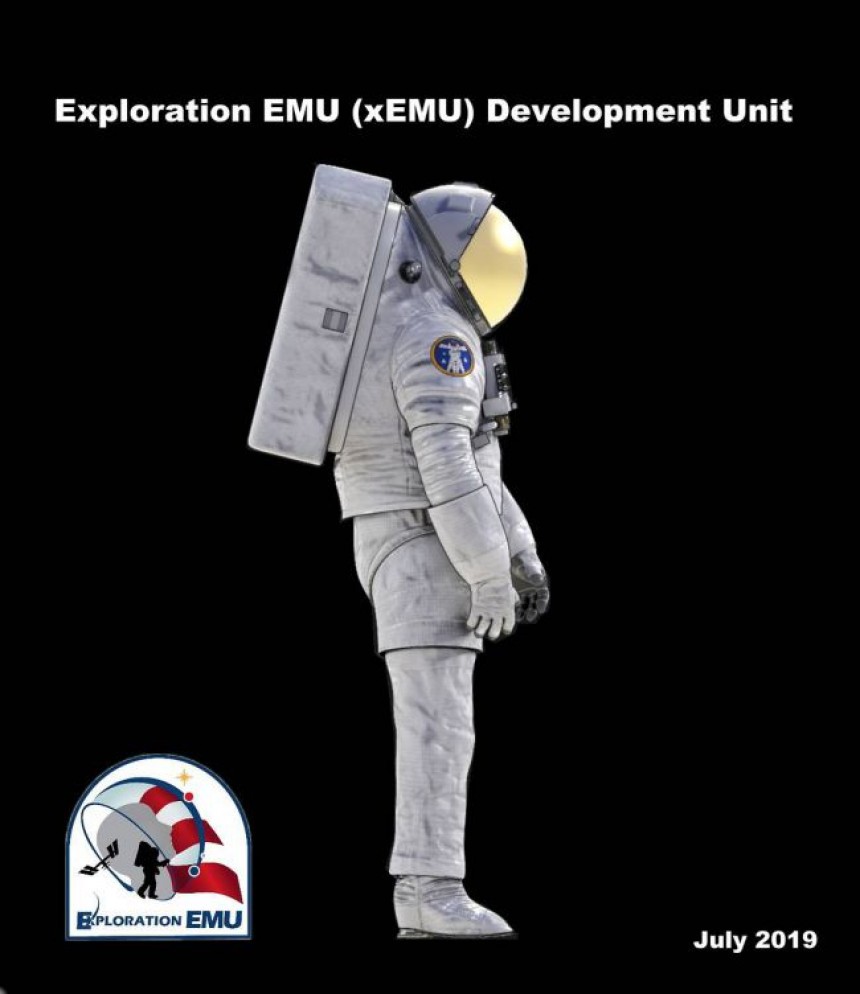

As for the actual spacesuits to be used for moonwalks, we already have a pretty good idea of how they’ll be like. NASA announced the first details back in 2019, saying it’s called Exploration Extravehicular Mobility Unit (xEMU). The thing is still in testing stages, with the official launch scheduled for 2023 (the first Artemis missions scheduled before that will have no use for it, as they will not land on the Moon).

The thing is based on the current EMU, but will of course come with upgrades. We’re not told if those changes pertain to the materials used in its construction, but we do know the new ones will be capable of withstanding temperatures ranging between minus 250 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 157 Celsius) in the shade and up to 250 degrees (121 Celsius) in the sun, keep fine dust particles out, and of course do the same for micrometeoroids.

Work at the Impact Lab will not end, and will continue for the foreseeable future, until NASA finds what it’s looking for. Next up is trying to come up with new types of aerogels than could be applied on materials and allow them to capture space debris without being damaged.

The people that have gone up to the International Space Station (ISS) over the years have gotten used to this ever-present danger, comfortable in the knowledge that the materials the spaceships and their suits are made of can do more than a decent job in protecting them against impacts.

But later this decade we’re going to the Moon, and there’s an entirely new ball game up there. Sure, we’ve been there before, but enough time has passed since to make us both wiser and more cautious.

Artemis is how the new Moon exploration program is called, and everything in it is brand new compared to Apollo, from the spacecraft to the mission and procedures. The astronauts' suits, their habitats, and even their vehicles are new, not only in design, but also in terms of materials as well.

The Glenn Research Center is the place where something called Ballistic Impact Lab resides. That would be a facility that houses a 40-foot-long air gun capable of shooting out one end various projectiles at speeds that can reach 2,000 mph (3,200 kph). Not quite the speed of a meteorite, but given how they shoot steel ball bearings, among other things, the results should come close enough.

A number of textiles and fabrics for Artemis have already been tested by NASA engineers this way, as the race is on to find out things like how many layers would be needed to stop micrometeoroid penetration.

The first series of tests also included materials being considered as building solutions for habitats, which need to be soft and flexible when left alone, but capable of turning very stiff is struck. Kind of like some non-Newtonian fluids, if you like.

The thing is based on the current EMU, but will of course come with upgrades. We’re not told if those changes pertain to the materials used in its construction, but we do know the new ones will be capable of withstanding temperatures ranging between minus 250 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 157 Celsius) in the shade and up to 250 degrees (121 Celsius) in the sun, keep fine dust particles out, and of course do the same for micrometeoroids.

Work at the Impact Lab will not end, and will continue for the foreseeable future, until NASA finds what it’s looking for. Next up is trying to come up with new types of aerogels than could be applied on materials and allow them to capture space debris without being damaged.