In recent years, there has been an increased interest in bendable electronics. And to be fair, the idea of having a mini-computer that you can mold into your hands like play-dough does sound quite fascinating. Well, as futuristic as it might be, it appears that we are closer to seeing it happen than we might think.

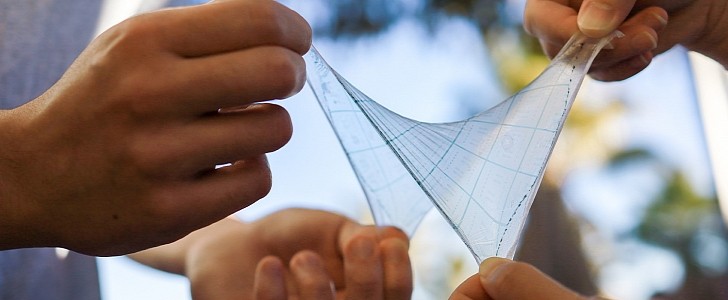

Stanford University researchers have been working on skin-like integrated circuits that can be stretched, bent, twisted, and folded while still functioning at full capacity. This may sound like something out of a sci-fi movie, but companies like Samsung are already on their way to develop a stretchy "electronic skin."

The engineers from Stanford have been focusing on the commercialization of this product, namely how to produce this new technology in large quantities for the public. Zhenan Bao, a chemical engineer, and her colleagues have recently published a new study describing how they have been working on printing stretchy integrated circuits on rubbery, skin-like materials. For this method, the group used the same equipment that makes solid silicon chips.

This allowed them to fit over 40,000 transistors in a single square centimeter of stretchable material. And if these digits sound like a lot, the team is pretty confident that it can double them. According to the team, that number would be enough to make simple circuits for on-skin sensors, body-scale networks, and possibly implantable bioelectronics.

The method they used is called photolithography, and it enhances elastic-transistor density by up to 100 times. It uses UV light to transfer a circuit layer by layer onto a solid surface. It's not a new process. It has been used for a long time in the semiconductor industry, but stretchable circuits were just not a thing up until now.

The issue was that the chemicals used to dissolve and wash away the light-resistant materials also washed away the skin-like polymers, aka the base for stretchy circuits. Scientists used the new discovery to create flexible circuits with electrical performance comparable to transistors used in today's computer displays.

For now, the method is still being tested and developed, but who knows, we might actually see stretchable electronics commercially available sooner than we might have thought.

The engineers from Stanford have been focusing on the commercialization of this product, namely how to produce this new technology in large quantities for the public. Zhenan Bao, a chemical engineer, and her colleagues have recently published a new study describing how they have been working on printing stretchy integrated circuits on rubbery, skin-like materials. For this method, the group used the same equipment that makes solid silicon chips.

This allowed them to fit over 40,000 transistors in a single square centimeter of stretchable material. And if these digits sound like a lot, the team is pretty confident that it can double them. According to the team, that number would be enough to make simple circuits for on-skin sensors, body-scale networks, and possibly implantable bioelectronics.

The method they used is called photolithography, and it enhances elastic-transistor density by up to 100 times. It uses UV light to transfer a circuit layer by layer onto a solid surface. It's not a new process. It has been used for a long time in the semiconductor industry, but stretchable circuits were just not a thing up until now.

The issue was that the chemicals used to dissolve and wash away the light-resistant materials also washed away the skin-like polymers, aka the base for stretchy circuits. Scientists used the new discovery to create flexible circuits with electrical performance comparable to transistors used in today's computer displays.

For now, the method is still being tested and developed, but who knows, we might actually see stretchable electronics commercially available sooner than we might have thought.