One of the most dangerous jobs our civilization has to offer its bravest members is that of a military pilot. In their current form, military aircraft offer high-speed rides, beautifully dangerous aerobatics capabilities, and explosive weaponry. All of that can end a pilot's life in a blink of an eye.

To be fair, people have always known flying can be dangerous. Ok, not flying itself, but the abrupt end to it. Just a few short years after the Wright brothers flew their contraption in North Carolina, people were already trying to find ways to bail out of an aircraft for whatever reason.

Early aviation pioneers already knew of a concept we now call a parachute. It was actually invented before the airplane, with Frenchman Louis-Sebastien Lenormand testing such life-saving devices by jumping out of trees and from the rooftops of city buildings in the 1800s.

Parachutes were ideal for saving the lives of pilots during aviation's early years. After all, airplanes of that era flew slow enough to allow people to simply climb out and drop to the ground. And after U.S. Army Captain Albert Berry made the first parachute jump from a moving aircraft in 1912, the role of parachutes was extended to include the drop of military forces behind enemy lines.

But as technology progressed and these flying machines became faster and more complicated, exiting a fighter airplane as you would a car was no longer viable. So something a lot better had to be invented. Enter the ejection seat.

The tech we know today by that name can trace its roots back to the 1910s, when a parachute maker by the name of Everard Calthrop patented such an idea. In the 1920s, thanks to Romanian inventor Anastase Dragomir, the modern-day layout of the ejection seat came to be.

There has been a great deal of designs since, and as fighter jets took over the world's air forces, they've become commonplace systems. They are designed to save pilots' lives in case of an emergency, and most of the time, if used timely and properly, they work as advertised.

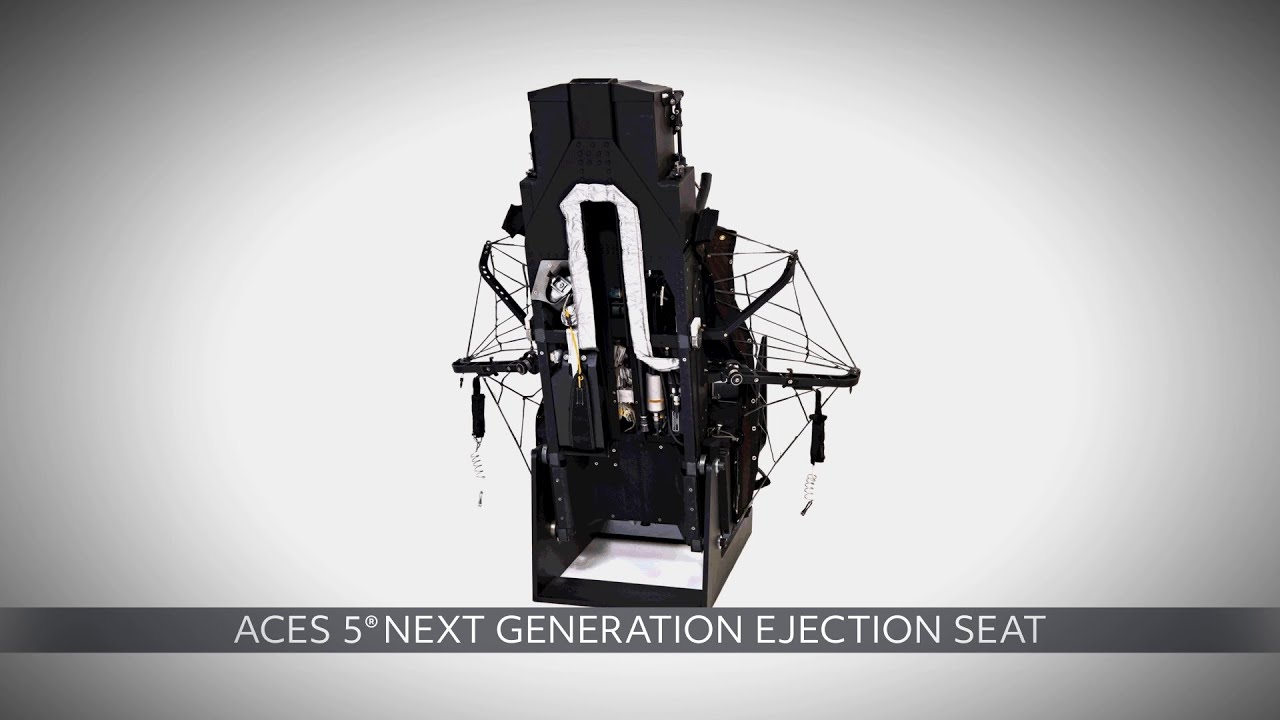

One of the companies involved in making ejection seats is Collins Aerospace. Back in the late 1970s, the company came up with something called the Advanced Concept Ejection Seat. ACES for short, it proved so successful that it rapidly spread to most of the military planes America is flying, including the A-10, F-15, F-16, F-22, and B-1, among others.

Until recently, the type of system being deployed was called ACES II, but closer to our time Collins introduced a new variant of the tech called ACES 5. Last week it made the headlines as it will become a standard feature on the T-7A Red Hawk trainer, and inspired us to have a closer look at how the thing works.

As you'll see in the two videos below this text, it's all pretty simple, really, doesn't take more than a couple of seconds, and is as safe as it can be for a system meant to push pilots out of their planes by means of rockets and explosives.

Based on the previous ACES variant, the new seat has been improved to be better than what's required for the F-35, with a risk of major head and neck injury for pilots using it of under five percent. We're also informed there's only a one percent chance of spinal injury when using the system's new catapult. As a bonus, a new parachute system should provide the "softest ride" available to ejecting pilots.

But how does the thing work? It's pretty simple, really, and, as said, it takes just a few seconds to remove the pilot from a crashing or burning plane.

The seat is just that, a seat, but with a few extras on the side. It has head, arm and leg restraints, a catapult, and a parachute.

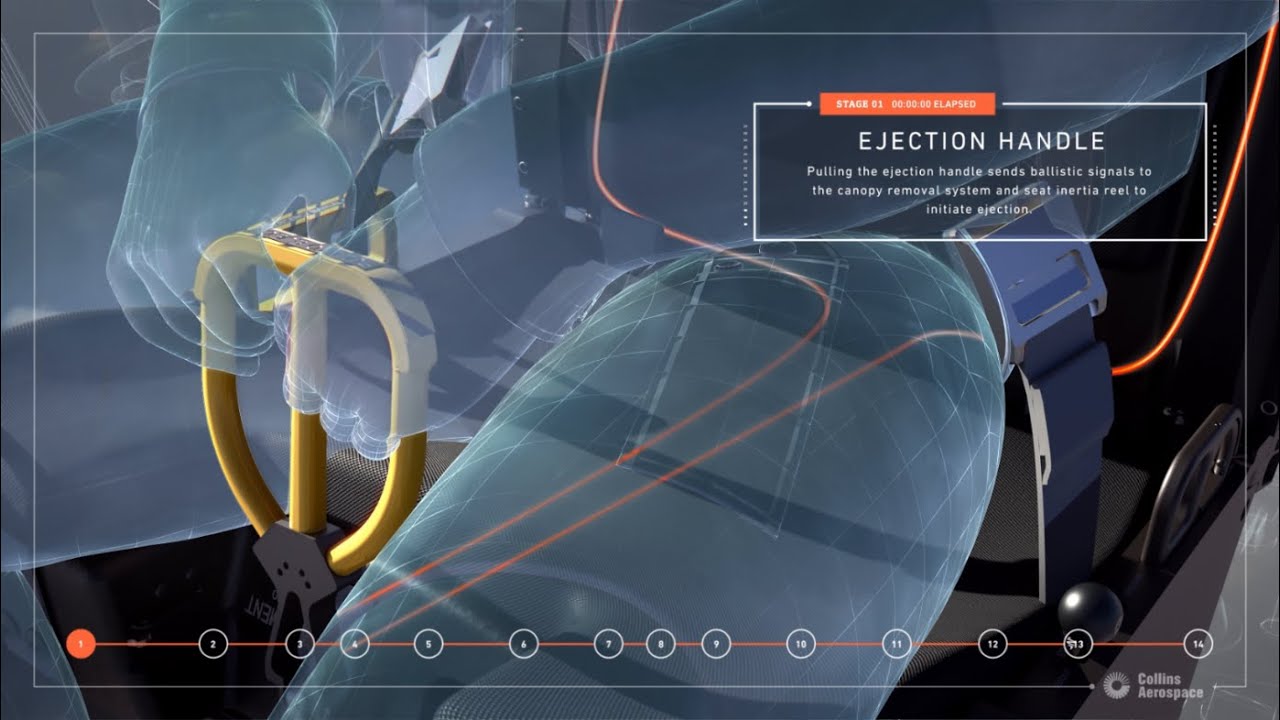

When the pilot pulls on the ejection handle, located on the bottom of the seat, between the legs, a signal is sent to the canopy removal system and the seat itself. The canopy is hit by a ballistic system and ejected first, so that the pilot doesn't slam into it.

At the same time, the seat belts, but also the head, arm and leg restraints tighten up so that the pilot remains in the seat and their arms and legs don't flap around, in danger of hitting something on the way out. The pilot's head is pushed down and secured in place.

With the canopy out of the way and the restraints firmly securing the pilot, the catapult pushes the seat out of the airplane. As soon as that happens, pitot tubes are deployed from the seat. You might be familiar with the term from the aviation industry. Pitot tubes are use to measure the air speed of an aircraft, and they do the same here, only for the seat.

These things are required because what comes next depends on the air speed and altitude of the plane at the time of the ejection. If both are high, rockets strapped to the seat kick in to control pitch and a drogue stabilization system deploys, keeping the seat stable until a more manageable speed and height are reached.

When that happens, the parachute deploys. In case of low-speed, low-altitude ejections, the parachute deploys directly, with no need for the drogue system to engage.

Unlike what you often see in movies, the pilot does not glide all the way down attached to the seat. In real life, a harness release cartridge separates the pilot from the seat.

All of the above might have taken you about a minute or two to read, but in real life everything happens in just 1.6 seconds.

As per Collins, there are thousands of ACES II systems in use with around 29 air forces worldwide, and a few hundred of the ACES 5 already. Since their introduction, these seats have been used hundreds of times, saving the lives of some 690 pilots.

Early aviation pioneers already knew of a concept we now call a parachute. It was actually invented before the airplane, with Frenchman Louis-Sebastien Lenormand testing such life-saving devices by jumping out of trees and from the rooftops of city buildings in the 1800s.

Parachutes were ideal for saving the lives of pilots during aviation's early years. After all, airplanes of that era flew slow enough to allow people to simply climb out and drop to the ground. And after U.S. Army Captain Albert Berry made the first parachute jump from a moving aircraft in 1912, the role of parachutes was extended to include the drop of military forces behind enemy lines.

But as technology progressed and these flying machines became faster and more complicated, exiting a fighter airplane as you would a car was no longer viable. So something a lot better had to be invented. Enter the ejection seat.

The tech we know today by that name can trace its roots back to the 1910s, when a parachute maker by the name of Everard Calthrop patented such an idea. In the 1920s, thanks to Romanian inventor Anastase Dragomir, the modern-day layout of the ejection seat came to be.

One of the companies involved in making ejection seats is Collins Aerospace. Back in the late 1970s, the company came up with something called the Advanced Concept Ejection Seat. ACES for short, it proved so successful that it rapidly spread to most of the military planes America is flying, including the A-10, F-15, F-16, F-22, and B-1, among others.

Until recently, the type of system being deployed was called ACES II, but closer to our time Collins introduced a new variant of the tech called ACES 5. Last week it made the headlines as it will become a standard feature on the T-7A Red Hawk trainer, and inspired us to have a closer look at how the thing works.

As you'll see in the two videos below this text, it's all pretty simple, really, doesn't take more than a couple of seconds, and is as safe as it can be for a system meant to push pilots out of their planes by means of rockets and explosives.

Based on the previous ACES variant, the new seat has been improved to be better than what's required for the F-35, with a risk of major head and neck injury for pilots using it of under five percent. We're also informed there's only a one percent chance of spinal injury when using the system's new catapult. As a bonus, a new parachute system should provide the "softest ride" available to ejecting pilots.

The seat is just that, a seat, but with a few extras on the side. It has head, arm and leg restraints, a catapult, and a parachute.

When the pilot pulls on the ejection handle, located on the bottom of the seat, between the legs, a signal is sent to the canopy removal system and the seat itself. The canopy is hit by a ballistic system and ejected first, so that the pilot doesn't slam into it.

At the same time, the seat belts, but also the head, arm and leg restraints tighten up so that the pilot remains in the seat and their arms and legs don't flap around, in danger of hitting something on the way out. The pilot's head is pushed down and secured in place.

With the canopy out of the way and the restraints firmly securing the pilot, the catapult pushes the seat out of the airplane. As soon as that happens, pitot tubes are deployed from the seat. You might be familiar with the term from the aviation industry. Pitot tubes are use to measure the air speed of an aircraft, and they do the same here, only for the seat.

These things are required because what comes next depends on the air speed and altitude of the plane at the time of the ejection. If both are high, rockets strapped to the seat kick in to control pitch and a drogue stabilization system deploys, keeping the seat stable until a more manageable speed and height are reached.

Unlike what you often see in movies, the pilot does not glide all the way down attached to the seat. In real life, a harness release cartridge separates the pilot from the seat.

All of the above might have taken you about a minute or two to read, but in real life everything happens in just 1.6 seconds.

As per Collins, there are thousands of ACES II systems in use with around 29 air forces worldwide, and a few hundred of the ACES 5 already. Since their introduction, these seats have been used hundreds of times, saving the lives of some 690 pilots.