Carriages were the first vehicles that required something to light their way. The very first things conceived to do that were lamps powered by candles, which suited these vehicles powered by horses pretty well. When horseless carriages first emerged, carriage lamps proved not to resist the higher speeds they could achieve. That was when engineers faced a new challenge: the new vehicle they had conceived would need more changes to be viable.

The deal was that people also had to leave their homes at night. The higher the speed, the further you have to be able to see to avoid obstacles. According to the Injury Facts study from the National Safety Council (NSC), 44.2% of all deadly accidents in 2021 occurred from 4 PM until midnight, despite the fact that night driving accounts for only around a quarter of overall traffic in the US. Although drowsiness plays a crucial role in these crashes, poor visibility must also take its toll. That's where better lighting can help.

The first electric headlamp was used in an early battery electric vehicle (BEV) in 1898. The Columbia was manufactured by a company appropriately called the Electric Vehicle Company. That early attempt was optional and faced challenges such as light filaments that would not stand automotive use. That was an early example of a lack of automotive-grade components.

Just try to imagine how hard it was for the filaments to keep it together in a vehicle that shook just like a carriage – and used the same kind of suspension – on roads that were far from being even. Phillips tried to address that in 1906 with a lamp that had a tungsten filament, which was – and still is – resistant to vibrations. Still, cold air could invade the headlights and cause thermal shocks, while dynamos were yet to be replaced by alternators in vehicles with internal combustion engines, among other issues. It would take years of testing before electric headlights were ready for the mainstream. Alternators in cars emerged in 1913 with Hispano Suiza, but they were very expensive and only started replacing dynamos in the 1960s – when silicon-diode rectifiers helped bring their prices down.

Ironically, the first vehicle to present a viable electric headlight was also the one that killed early BEVs. In 1912, the Cadillac Model 30 became the first car with an electric system. Apart from the new headlamps that could be used even during rain or snow, it also had an electric ignition and an electric starter instead of a hand crank that broke arms and often killed those trying to start a car. With the better range, lower weight, and higher convenience compared to the electric vehicles of the time, ICE cars prevailed.

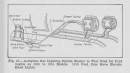

Drivers would also have to get out of their vehicles to turn the headlights on and off, which was quite inconvenient on rainy and cold days. Cadillac fixed that in 1917 in the Model 55 and Model 57, which presented a lever to turn the lights on inside the cabin. It was possible to lower the light beam – a solution called dipping headlamps – through a mechanical system of rods and linkages connected to the reflectors and operated by another lever on the steering column. However, other solutions emerged to avoid flash blinding other drivers and road users.

In 1924, Osram presented the Bilux bulb, which had individual filaments for the high and low beams. It had a performance of 60 meters (65.6 yards) and an illuminance of 1 lux. Modern halogen headlights present around 750 lux. The Guide Lamp Company presented a similar product called Duplo in 1925. Engineers also developed the headlight dimmer pedal, which first appeared in 1927 and allowed drivers to regulate the beam with their feet. As unusual as that may sound, the system remained in production until the early 1990s.

In 1939, General Electric developed the first sealed-beam lamp for automotive use, which came with its own reflector and a resistant glass lens. Curiously, the US government determined in 1940 that all cars sold in the country would have to go with two 7-inch (178 millimeters) round sealed-beam headlights. It is not clear if that was because of how superior the equipment was or if General Electric persuaded the American government at the time that it sold the right parts for night driving.

Whatever the reason was, it restricted the design of vehicles, which had to have the same headlights. That lasted until 1957 – when the US government gave carmakers the option to use four 5.75-in (146 mm) round sealed-beam headlamps. In 1974, rectangular sealed-beam components became another option. The rest of the world did not face the same restrictions.

After the automotive industry was on the same page, the next challenge was to achieve smarter and more efficient lighting means. That was when it came up with high-intensity discharge (HID) systems, also known as xenon headlights. They made their premiere on the second-generation BMW 7 Series (E32) in 1991. People soon got fascinated with the blue light these headlights emitted, and it became a status symbol among car enthusiasts. They were a lot less thrilled by the price to fix these headlights should anything go wrong.

All HID lights require a ballast, including an ignitor, which controls the current sent to the bulb. The ignitor comes as a stand-alone element in D2 and D4 systems and as a bulb-integrated element in D1 and D3 assemblies. Compared to the other types of headlamps, xenon units provide way more light, obviously improving visibility when driving at night. However, don't imagine that using high-intensity discharge lights is only milk and honey.

First of all, xenon lights produce considerably more glare than the other types of headlamps. Secondly, all systems have to be equipped with headlight lens cleaning systems and automatic beam leveling control to reduce the amount of glare produced by these lamps. Last but not least, HID is way more expensive than any of the other types of lights, counting here both the purchase and the installation process. Prices have dropped as the production scale increased, but HID headlights also lost their position as the latest tech to light-emitting diode (LED) headlights, which made their premiere on the Lexus LS 600h in 2006.

According to Car and Driver, xenon lights last around 15,000 hours, while LED lights can have a lifespan of 45,000 hours (three times that of their older siblings). They are also very bright and energy-efficient, which is the reason they equip most BEVs produced nowadays. That also created an issue that automakers probably did not anticipate until the first complaints started to emerge.

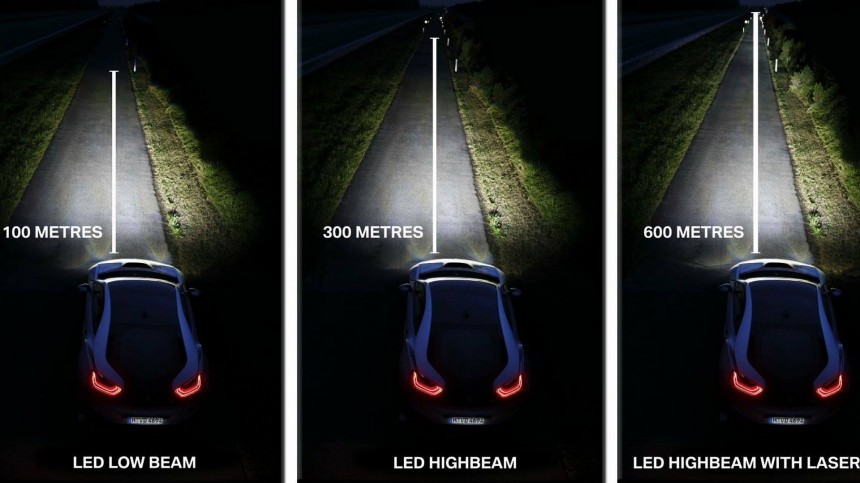

That did not stop innovation in automotive lighting. The latest developments are laser headlights and the Advanced Front-Lighting System (AFS, aka adaptive headlights). The former made their official debut in production cars on the BMW i8 in 2014. The system works with mirrors that direct a laser beam into phosphors. The resulting light is very bright and demands half of the energy LED headlights consume. By now, it should be in several new vehicles if it was not so expensive. One of the vehicles that use the technology is the eighth-generation Rolls-Royce Phantom. Its high beam has a reach of 600 m (656 yards) – ten times that of the 1924 Osram Bilux bulb.

As for AFS, it is basically a high-end technology relying on a series of factors, including steering angle and a number of sensors, to determine the driving direction and slightly adjust the focus of the front-lighting system. A few prototypes rely on GPS and navigation details to anticipate road curves and adjust the lighting directions before entering a turn. In addition, numerous automakers installed light sensors to determine the moment the driver needs the lights (such as in tunnels and even during the night) and automatically turn on the headlamps without driver assistance. Toyota, Skoda, Nissan, Ferrari, Mazda, and several other carmakers are installing adaptive headlights in their cars. According to Hella, low-beam lamps are a compromise solution that AFS should fix for good. The technology can use HID or LEDs as its light source.

Curiously, the more things evolve, the closer they resemble sealed-beam headlights in the sense that you often have to replace the entire component, not just the bulb. That is particularly true in vehicles with LED daytime running lights (DRLs).

If an LED DRL fails, you may have to replace the entire headlight. Considering light bulbs should always be replaced in pairs, it may be the same story with these components, which doubles the probable expense.

Even though they are often regarded as safety enhancers, DRLs have caused quite some controversy worldwide. European regulators, for instance, raised questions regarding how they alter fuel economy and CO2 emissions. The lights are powered by electric power, which the alternator in an ICE vehicle generates. That means the engine is helping produce it by burning fuel. In electric cars, that energy comes from the battery pack, which makes it less efficient. The good news is that this does not generate direct CO2 emissions in these vehicles. Depending on how much safer DRLs make vehicles, this is a discussion that regulators should be embarrassed to bring up. Unless they think people should drive in the dark, they should celebrate technology advancements, particularly those that take repairability into consideration. It may be the case that they don't want us to drive at all, but that's a different discussion.

When did the first car headlight come out?

The first vehicle headlamps were officially introduced during the 1880s and were based on acetylene and oil, similar to the old gas lamps. In essence, these two substances were used to fuel the headlamps. Although they were often praised for their resistance to air currents and challenging weather conditions – such as snow and rain – carbide lamps could present leaks and even explosions. They were also optional: Ford only turned them into standard equipment in 1909 on the open car Model T. These headlights became the preferred industry solution for driving at night until something better and more practical came to replace them.The first electric headlamp was used in an early battery electric vehicle (BEV) in 1898. The Columbia was manufactured by a company appropriately called the Electric Vehicle Company. That early attempt was optional and faced challenges such as light filaments that would not stand automotive use. That was an early example of a lack of automotive-grade components.

Just try to imagine how hard it was for the filaments to keep it together in a vehicle that shook just like a carriage – and used the same kind of suspension – on roads that were far from being even. Phillips tried to address that in 1906 with a lamp that had a tungsten filament, which was – and still is – resistant to vibrations. Still, cold air could invade the headlights and cause thermal shocks, while dynamos were yet to be replaced by alternators in vehicles with internal combustion engines, among other issues. It would take years of testing before electric headlights were ready for the mainstream. Alternators in cars emerged in 1913 with Hispano Suiza, but they were very expensive and only started replacing dynamos in the 1960s – when silicon-diode rectifiers helped bring their prices down.

Low-beam headlights to kill flash blindness

Soon people started noticing that you could not have the same light for every situation. Flash blindness episodes and even some crashes were probably what led the Guide Lamp Company to introduce low-beam headlights in 1915. It was not as convenient as what you now have in your car: the headlights were adjustable, but you had to step out of the vehicle to regulate them. That was the same year Ford made electric headlamps standard on the Model T. While one company was trying to address safety concerns related to headlights, the other did not have time to incorporate that into its products. In those early days, there were plenty of details yet to fix, such as how to put headlamps to work.Drivers would also have to get out of their vehicles to turn the headlights on and off, which was quite inconvenient on rainy and cold days. Cadillac fixed that in 1917 in the Model 55 and Model 57, which presented a lever to turn the lights on inside the cabin. It was possible to lower the light beam – a solution called dipping headlamps – through a mechanical system of rods and linkages connected to the reflectors and operated by another lever on the steering column. However, other solutions emerged to avoid flash blinding other drivers and road users.

In 1924, Osram presented the Bilux bulb, which had individual filaments for the high and low beams. It had a performance of 60 meters (65.6 yards) and an illuminance of 1 lux. Modern halogen headlights present around 750 lux. The Guide Lamp Company presented a similar product called Duplo in 1925. Engineers also developed the headlight dimmer pedal, which first appeared in 1927 and allowed drivers to regulate the beam with their feet. As unusual as that may sound, the system remained in production until the early 1990s.

Whatever the reason was, it restricted the design of vehicles, which had to have the same headlights. That lasted until 1957 – when the US government gave carmakers the option to use four 5.75-in (146 mm) round sealed-beam headlamps. In 1974, rectangular sealed-beam components became another option. The rest of the world did not face the same restrictions.

Replaceable halogen bulbs caused a revolution, but the US had to wait

A European consortium of lighting companies presented the first replaceable halogen headlamp bulb in 1962, the H1. Other formats were eventually introduced, such as H4, but the deal with the H1 was that it prevented having to spend a lot of money on new headlights just because the lamp died. Halogen light bulbs also lasted much longer than those that only had tungsten filaments, which turned the inside of the glass dark as they deteriorated. With halogen inside that glass chamber, the tungsten combines with the gas and returns to the filament, extending the component's life. The US government only thought that was a good idea in 1983 – after Ford petitioned to use swappable halogen lamps and polycarbonate lenses in its cars. The American automaker asked for that in 1981.After the automotive industry was on the same page, the next challenge was to achieve smarter and more efficient lighting means. That was when it came up with high-intensity discharge (HID) systems, also known as xenon headlights. They made their premiere on the second-generation BMW 7 Series (E32) in 1991. People soon got fascinated with the blue light these headlights emitted, and it became a status symbol among car enthusiasts. They were a lot less thrilled by the price to fix these headlights should anything go wrong.

First of all, xenon lights produce considerably more glare than the other types of headlamps. Secondly, all systems have to be equipped with headlight lens cleaning systems and automatic beam leveling control to reduce the amount of glare produced by these lamps. Last but not least, HID is way more expensive than any of the other types of lights, counting here both the purchase and the installation process. Prices have dropped as the production scale increased, but HID headlights also lost their position as the latest tech to light-emitting diode (LED) headlights, which made their premiere on the Lexus LS 600h in 2006.

According to Car and Driver, xenon lights last around 15,000 hours, while LED lights can have a lifespan of 45,000 hours (three times that of their older siblings). They are also very bright and energy-efficient, which is the reason they equip most BEVs produced nowadays. That also created an issue that automakers probably did not anticipate until the first complaints started to emerge.

LED headlights have problems with cold weather

LED headlamps do not emit infrared energy, also known as invisible heat. In cold weather, that keeps the lenses cold, which stimulates ice to build up over them. Companies that duly tested their cars know about the problem and tried to transfer the heat in the back of LEDs to the inner part of the lenses. Those that ignored this part of vehicle development are either giving their customers lame excuses or pretending the issue does not exist.That did not stop innovation in automotive lighting. The latest developments are laser headlights and the Advanced Front-Lighting System (AFS, aka adaptive headlights). The former made their official debut in production cars on the BMW i8 in 2014. The system works with mirrors that direct a laser beam into phosphors. The resulting light is very bright and demands half of the energy LED headlights consume. By now, it should be in several new vehicles if it was not so expensive. One of the vehicles that use the technology is the eighth-generation Rolls-Royce Phantom. Its high beam has a reach of 600 m (656 yards) – ten times that of the 1924 Osram Bilux bulb.

Curiously, the more things evolve, the closer they resemble sealed-beam headlights in the sense that you often have to replace the entire component, not just the bulb. That is particularly true in vehicles with LED daytime running lights (DRLs).

DRLs enhance safety, so let them spend energy

The first countries to impose strict regulations regarding these lights were those located in Scandinavia. Sweden was the first nation to adopt special laws in 1977, followed by Norway in 1986, Iceland in 1988, and Denmark in 1990. Finland made DRLs mandatory on all roads in 1997. They are supposed to be used at all times, regardless of weather conditions or other factors. This type of lighting allows other drivers on the road to better notice an incoming vehicle, especially on highway or country roads.Even though they are often regarded as safety enhancers, DRLs have caused quite some controversy worldwide. European regulators, for instance, raised questions regarding how they alter fuel economy and CO2 emissions. The lights are powered by electric power, which the alternator in an ICE vehicle generates. That means the engine is helping produce it by burning fuel. In electric cars, that energy comes from the battery pack, which makes it less efficient. The good news is that this does not generate direct CO2 emissions in these vehicles. Depending on how much safer DRLs make vehicles, this is a discussion that regulators should be embarrassed to bring up. Unless they think people should drive in the dark, they should celebrate technology advancements, particularly those that take repairability into consideration. It may be the case that they don't want us to drive at all, but that's a different discussion.