The Italians are known the world over for not giving a rat's behind about what foreign nationals think of their engineering. More to the point, it's because the Italians really know how to build exciting machines. In the automotive world, the Lamborghini Countach and the Ferrari F40 are classic cases in point. But this philosophy applies to aviation as well.

This is the remarkable story of the Caproni Ca.60 Transaero, a nine-winged flying boat airliner that could have only been built in Italy. By 1921, the world's very first transatlantic flight had only occurred two years prior. John Alcock and Arthur Brown may have crash-landed their British Vickers Vimy biplane after flying from Nova Scotia, Canada, all the way to County Galway, Ireland.

But that didn't stop aeronautical engineers the world over from thinking they could do it better. More specifically, an Italian engineer by the name of Giovanni Battista Caproni had a vision for something far grander. If a modified First World War bomber going transatlantic knocked people's socks off, imagine how they'd react to a 100-seater flying boat passenger airliner managing the same feat.

At least, that's what people with modern sensibilities are left to assume about the genesis of this creation. During the First World War, "Gianni" Caproni busied himself building some of the very first heavy bombers used in combat on either side of the conflict. One of Caproni's designs, the Ca.36 biplane bomber, is preserved to this day at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio, which should only speak to how important and innovative Caproni's designs could be in their day.

But even before the war, Caproni envisioned a day where 100-plus passenger transatlantic airliners were more routine than a novelty. The mass conversion of many of his WWI bomber designs into some of the first passenger airliners in Europe ensured Caproni had the experience to make it happen. In some ways, the patent that Gianni Caproni took out for his design in 1919 resembled a modern airliner in layout far more than it did a conventional aircraft of the day.

At a time when most airplanes struggled to haul ten passengers, the notion one could carry 100 or more across the expanse of the Atlantic Ocean might as well have been witchcraft. As a result, Caproni's design with met with mild skepticism from some people and outright rejection by experts. Most notably, the former Italian WWI general and aviation theorist Giulio Douhet believed that Caproni's idea was wrong-headed in the most polite terms. What if a flying boat laden with passengers flies into the drink unexpectedly? That would spell doom for anyone on board.

Or at least that's the rationale behind Caproni's detractors. On the face of it, these criticisms had a point. But Gianni Caproni was prepared for the haters. In response, a number of measures were implemented with the goal of increasing safety. Key trinkets like engine redundancy allowed Caproni's design to land safely in the event of engine failure, which is a stalwart feature of modern aviation.

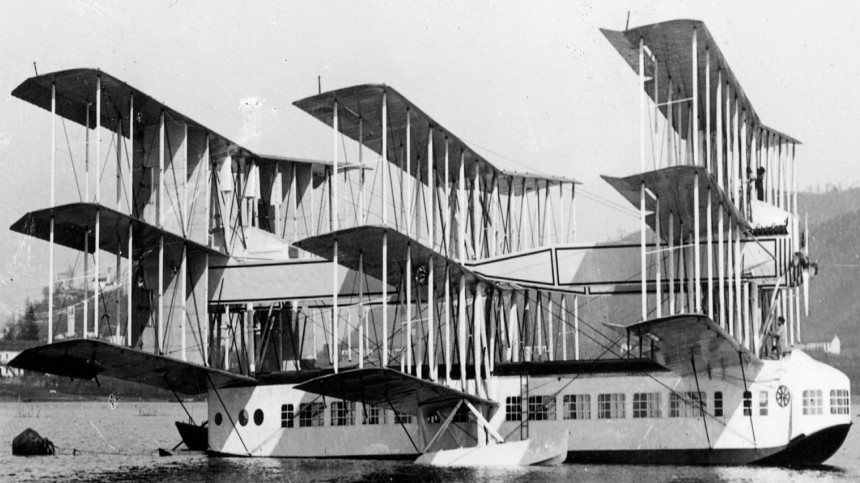

In the days when it was assumed two or more sets of wings provided optimal lift, Caproni's plan called for a set of nine massive wings arranged three a piece down the length of the concept's fuselage. Of course, we in the modern day know that extra wings cause far more parasitic drag than the lift they generate. That didn't stop a novel Noviplano (nine-wing) layout from becoming the standard for what Caproni called the Transaero.

The design with the same amount of wings as your average B-Dubs order began production at Caproni's facility in Taliedo, on the outskirts of Milan, in late 1919. Anyone familiar with the story of the infernal Christmas Bullet knows the story of the Liberty L-12 V12 aeronautical engine. The very same engines that powered the two doomed Christmas Bullets also powered the Caproni Transaero. It's as if the U.S. Military didn't get the hint the first time someone asked to use their flagship engine in untested experimental airframes of questionable origin.

But unlike Dr. William Whitney Christmas, Gianni Caproni was at least a legit aerospace engineer. With roughly 400 horsepower from each engine to play with, the Ca.60 Transaero had respectable power for its day, nearly 3,200 horsepower in total. In theory, Gianni Caproni hoped the Transaero would cruise at 80 miles per hour (130 kph) while transporting upwards of 100 people across the vast oceans in abject comfort. From a modern perspective, the Ca.60 was the Airbus A380 of its day, the largest airliner around.

The 26,000 kg (57,320 lb) fully loaded Caproni Ca.60 Transaero was ready for its first flight by the beginning of 1921, leaving its production hangar for photographic posterity's sake in January of that year. Upon each of the 30-meter long (98 ft 5 in) wings, a set of ailerons was mounted. Through differentiation in the positions of the left-side and right-side ailerons, the aircraft could ascend and descend in the same way it would with conventional elevators. Interestingly, the airframe lacked a horizontal stabilizer.

Though most aerospace engineers today are liable to think that's a little "sus," Gianni Caproni was eager to get his creation airborne. On the waters of Lake Maggiore in the Alps between Italy and Southern Switzerland, Caproni introduced his creation in February 1921. Some of Gianni Caproni's aerospace buddies were present for the Ca.60's first water taxi test. With famous names like Alessandro Tonini and Giulio Macchi of the Aermacchi Company and Raffaele Conflenti of the SIAI-Marhchetti group in attendance, the Transaero had decent handling traits in the water.

But good handling in the water doesn't necessarily mean the same in the air. Because record-keeping was pretty suspect at times in early aviation, it's a bit unclear when exactly the Ca.60 took its first flight. Some sources peg the date as February 12th or Mach 2nd, 1921, with Caproni's pilot Federico Semprini at the controls. Whatever the case, this feat made the Ca.60 Transaero one of the largest aircraft ever to fly.

Even if a few hundred kilos of ballast was needed to make it happen, it was a remarkable feat nonetheless. But it would be the last time the Transaero landed in one piece. Two days later, on March 4th, 1921, Federico Semprini is believed to have pulled back on the control yoke for takeoff too quickly, causing the aircraft to pitch up violently, stall out, and flop right back down to the water tail-first.

The resulting crash rippled the aircraft in two, with only the rear-facing two-thirds remaining entirely intact. Even if the aircraft was theoretically salvageable, the cost of repair would be astronomical. As such, the heavily damaged airframe was scrapped, leaving its true abilities up in the air forever. Ever since that fateful day, mild conspiracy theories regarding the particulars of that accident continued to make their rounds in aviation enthusiast circles.

Some claimed the Ca.60s pilot was attempting to steer clear of a steamboat in its immediate takeoff path. Others claim the sand-based ballast used to help lift the plane into the air came loose on takeoff and shifted the aircraft's center of mass to a dangerous degree. In the end, the answer will probably never be known for certain.

Today, bits and pieces that remain of Caproni's grandest idea are housed on display at the Gianni Caproni Museum of Aeronautics right beside the Trento Airport in Trento, Northern Italy. As the oldest aviation museum in all of Italy, the remains of one of the most ambitious, outrageous, and ironically respectable designs of the late pioneer age of aviation serve as the museum's main attraction.

It's easy to mock very overtly Italian designs with as many engines as a Lamborghini Urus has cylinders. But always remember, there'd be no Boeing 747, no Airbus A380, without the Caproni Ca.60 Transaero. For that, we owe Gianni Caproni our utmost thanks.

But that didn't stop aeronautical engineers the world over from thinking they could do it better. More specifically, an Italian engineer by the name of Giovanni Battista Caproni had a vision for something far grander. If a modified First World War bomber going transatlantic knocked people's socks off, imagine how they'd react to a 100-seater flying boat passenger airliner managing the same feat.

At least, that's what people with modern sensibilities are left to assume about the genesis of this creation. During the First World War, "Gianni" Caproni busied himself building some of the very first heavy bombers used in combat on either side of the conflict. One of Caproni's designs, the Ca.36 biplane bomber, is preserved to this day at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio, which should only speak to how important and innovative Caproni's designs could be in their day.

But even before the war, Caproni envisioned a day where 100-plus passenger transatlantic airliners were more routine than a novelty. The mass conversion of many of his WWI bomber designs into some of the first passenger airliners in Europe ensured Caproni had the experience to make it happen. In some ways, the patent that Gianni Caproni took out for his design in 1919 resembled a modern airliner in layout far more than it did a conventional aircraft of the day.

Or at least that's the rationale behind Caproni's detractors. On the face of it, these criticisms had a point. But Gianni Caproni was prepared for the haters. In response, a number of measures were implemented with the goal of increasing safety. Key trinkets like engine redundancy allowed Caproni's design to land safely in the event of engine failure, which is a stalwart feature of modern aviation.

In the days when it was assumed two or more sets of wings provided optimal lift, Caproni's plan called for a set of nine massive wings arranged three a piece down the length of the concept's fuselage. Of course, we in the modern day know that extra wings cause far more parasitic drag than the lift they generate. That didn't stop a novel Noviplano (nine-wing) layout from becoming the standard for what Caproni called the Transaero.

The design with the same amount of wings as your average B-Dubs order began production at Caproni's facility in Taliedo, on the outskirts of Milan, in late 1919. Anyone familiar with the story of the infernal Christmas Bullet knows the story of the Liberty L-12 V12 aeronautical engine. The very same engines that powered the two doomed Christmas Bullets also powered the Caproni Transaero. It's as if the U.S. Military didn't get the hint the first time someone asked to use their flagship engine in untested experimental airframes of questionable origin.

The 26,000 kg (57,320 lb) fully loaded Caproni Ca.60 Transaero was ready for its first flight by the beginning of 1921, leaving its production hangar for photographic posterity's sake in January of that year. Upon each of the 30-meter long (98 ft 5 in) wings, a set of ailerons was mounted. Through differentiation in the positions of the left-side and right-side ailerons, the aircraft could ascend and descend in the same way it would with conventional elevators. Interestingly, the airframe lacked a horizontal stabilizer.

Though most aerospace engineers today are liable to think that's a little "sus," Gianni Caproni was eager to get his creation airborne. On the waters of Lake Maggiore in the Alps between Italy and Southern Switzerland, Caproni introduced his creation in February 1921. Some of Gianni Caproni's aerospace buddies were present for the Ca.60's first water taxi test. With famous names like Alessandro Tonini and Giulio Macchi of the Aermacchi Company and Raffaele Conflenti of the SIAI-Marhchetti group in attendance, the Transaero had decent handling traits in the water.

But good handling in the water doesn't necessarily mean the same in the air. Because record-keeping was pretty suspect at times in early aviation, it's a bit unclear when exactly the Ca.60 took its first flight. Some sources peg the date as February 12th or Mach 2nd, 1921, with Caproni's pilot Federico Semprini at the controls. Whatever the case, this feat made the Ca.60 Transaero one of the largest aircraft ever to fly.

The resulting crash rippled the aircraft in two, with only the rear-facing two-thirds remaining entirely intact. Even if the aircraft was theoretically salvageable, the cost of repair would be astronomical. As such, the heavily damaged airframe was scrapped, leaving its true abilities up in the air forever. Ever since that fateful day, mild conspiracy theories regarding the particulars of that accident continued to make their rounds in aviation enthusiast circles.

Some claimed the Ca.60s pilot was attempting to steer clear of a steamboat in its immediate takeoff path. Others claim the sand-based ballast used to help lift the plane into the air came loose on takeoff and shifted the aircraft's center of mass to a dangerous degree. In the end, the answer will probably never be known for certain.

Today, bits and pieces that remain of Caproni's grandest idea are housed on display at the Gianni Caproni Museum of Aeronautics right beside the Trento Airport in Trento, Northern Italy. As the oldest aviation museum in all of Italy, the remains of one of the most ambitious, outrageous, and ironically respectable designs of the late pioneer age of aviation serve as the museum's main attraction.