Airports are kind of a pain in the you-know-what for most cities. They take up more land than most zip codes, fill the air with CO2 and noise pollution, and in some cases, the property values of the homes near a major international airport are still just as expensive as the surrounding city. Just with more turbofan engines spooling ferociously at all hours of the day.

Taking the tarmac and the runway out of the equation and replacing them with natural stretches of open water won't solve all of these problems. But in the early days of aviation, most pilots would have probably told you they'd prefer to take off from the sea than on dry land. Of course, aviation had its beginnings in a grassy field in North Carolina. But it didn't take early aviators long to understand the benefits of long, open spaces to take off on top of.

In an era when aero engines were underpowered and spat oil in your face for most of the flight, the more space, the better was a popular viewpoint. For this purpose, bodies of water were all nothing but perfection. It's generally agreed upon that the first example of a seaplane, i.e., either a flying boat with a ship-like hull or a float plane with pontoons for landing gear, was built in 1898 by the Austrian inventor Wilhelm Kress.

However, blueprint patents for similar designs precede him at least somewhat. His invention was named the Kress Drachenflieger (Dragon-flier). The Drachenflieger's automotive-derived Daimler produced 30 horsepower and wiped out during a taxiing test before it could ever get out of the water.

Over the next decade, Kress's design philosophies were modified to fit a growing understanding of the ins and outs of how powered aviation truly worked. French aviator François Denhaut is credited with designing the first seaplane with a boat-like hull. Or, as we call it, a flying boat.

Before long, seaplanes had made their way overseas to the United States in earnest. New York State native and iconic pioneer aviator Glenn Curtiss especially used seaplane designs to make his name in aviation after a career building motorcycles and bicycles. Curtiss's Model E first took off from Keuka Lake in New York's Finger Lakes region on 25 February 1911, with the faster Model F taking off in January 1912.

Curtiss was awarded the U.S. National Aeronautic Association's Collier Trophy for excellence in the innovation of aviation back to back in 1911 and 1912 for his efforts in the field of "hydro-aeroplanes," as they were called at the time. Before long, seaplanes began to form the backbone of an ever-expanding global aviation sector that struggled to find plots of flat, solid land to launch airplanes on.

Companies like Curtiss, but also Sopwith, Saunders-Roe, and Felixstowe from Great Britain, Fokker in the Netherlands, and Hansa-Brandenburg in Germany were all testing and manufacturing water-dwelling seaplanes even before the start of the First World War in some cases. The type would become a vital part of the war effort for both the Allied and Central powers.

If the advancements in seaplane technology before the war laid the groundwork for a renaissance, the end of said war kicked it into action. Once peace was signed in 1918, the importance of seaplanes in a global peacetime economy would only grow exponentially. One that, in the beginning, was largely formed on the backs of ex-Army Air Service airplanes repurposed for civil use.

Around the world, services like cargo and mail transport, military trainer airplanes, and even the earliest airliners opted for a water-based takeoff and landing in the years before World War II. At this time, the Curtiss NC-4 became the first airplane to cross the Atlantic Ocean.With several landings along the way to rest and refuel, of course.

The first commercial passenger transport seaplane business was founded in 1923 as a puddle jumper service between the Channel Islands between the U.K. and France. Soon after, wealthy residents of New York State's Long Island region began riding commercial seaplanes as their daily commute between their homes on the affluent North Short to their offices on Wall Street in Manhattan via the East and Hudson Rivers.

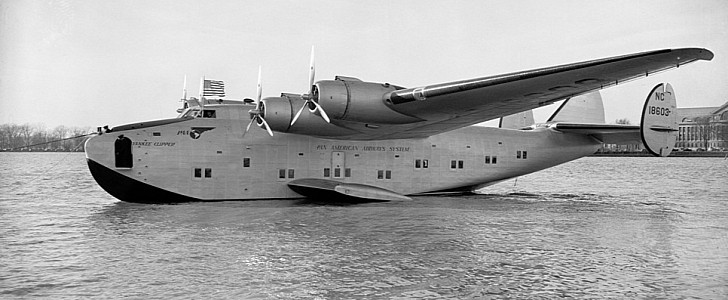

Across the ocean in Germany, the Dornier Do X became the largest, heaviest commercial airliner ever to fly in July 1929. The largest airplane in the United Kingdom at that time, the Short Sarafand, was also a flying boat with a biplane wing configuration, first flying in 1932. By 1939, the Boeing 314 Clipper monoplane took to the skies for the first time.

Based in part on the failed XB-15 heavy bomber prototype and one of the first flagship airplanes of the Pan Am airline, the Clipper flying boat paved the way for the iconic 707 and 747. Doing so by helping to generate the revenue Boeing needed to be able to innovate. Of course, building a fair percent of every American Second World War strategic bomber of significance also helped tremendously.

During World War II, the seaplane evolved with the changes in contemporary warfare. On both the Allied and Axis sides, seaplanes grew larger, more powerful, and carried deadlier armament than ever before. On the Allied side, flying boats like the Grumman G-21 Goose, Consolidated PBY Catalina, and Short S.25 Sunderland flew adversarially against German and Japanese flying boats like the Blohm and Voss BV-138 Wiking, and Kawanishi H8K "Emily."

The U.S. Army Air Corps even managed to fit a pair of pontoons underneath a Grumman F4F Wildcat and a Douglas C-47 Skytrain for a trial run during this time. The Axis did a very similar test with the Japanese A6M Zero among a host of Imperial Japanese floatplanes. But with the war's conclusion in 1945, the era of dominance by seaplanes was well and truly finished.

Years of warfare taught militaries and civilians alike how to build large land-based airfields in relatively short periods. More powerful aero engines that could take off at shorter distances meant the smoothness of a tarmac takeoff quickly rendered sea planes largely obsolete. A handful last hurrahs came from the British Saunders-Roe Princess turboprop airliner and the positively colossal American Hughes H-4 Hercules-Spruce Goose. The Martin JRM Mars also deserves a mention in this time period, among a few other outliers.

The Hughes H-4 specifically, was the largest airplane ever flown for a staggering period between 1947 and 2019. Today, only a handful of companies globally produce flying boats. Almost all turboprop cargo transports, most often built in either China, Japan, or Canada. As for their seaplane cousin float planes, they're almost strictly the domain of small private airplanes like Cessnas, with a few exceptions.

In 2022, it's almost unfathomable to believe that in the distant past, takeoff and landing by water were by far the preferred method.

Check back soon for more from Sea Month here on autoevolution.

In an era when aero engines were underpowered and spat oil in your face for most of the flight, the more space, the better was a popular viewpoint. For this purpose, bodies of water were all nothing but perfection. It's generally agreed upon that the first example of a seaplane, i.e., either a flying boat with a ship-like hull or a float plane with pontoons for landing gear, was built in 1898 by the Austrian inventor Wilhelm Kress.

However, blueprint patents for similar designs precede him at least somewhat. His invention was named the Kress Drachenflieger (Dragon-flier). The Drachenflieger's automotive-derived Daimler produced 30 horsepower and wiped out during a taxiing test before it could ever get out of the water.

Over the next decade, Kress's design philosophies were modified to fit a growing understanding of the ins and outs of how powered aviation truly worked. French aviator François Denhaut is credited with designing the first seaplane with a boat-like hull. Or, as we call it, a flying boat.

Curtiss was awarded the U.S. National Aeronautic Association's Collier Trophy for excellence in the innovation of aviation back to back in 1911 and 1912 for his efforts in the field of "hydro-aeroplanes," as they were called at the time. Before long, seaplanes began to form the backbone of an ever-expanding global aviation sector that struggled to find plots of flat, solid land to launch airplanes on.

Companies like Curtiss, but also Sopwith, Saunders-Roe, and Felixstowe from Great Britain, Fokker in the Netherlands, and Hansa-Brandenburg in Germany were all testing and manufacturing water-dwelling seaplanes even before the start of the First World War in some cases. The type would become a vital part of the war effort for both the Allied and Central powers.

If the advancements in seaplane technology before the war laid the groundwork for a renaissance, the end of said war kicked it into action. Once peace was signed in 1918, the importance of seaplanes in a global peacetime economy would only grow exponentially. One that, in the beginning, was largely formed on the backs of ex-Army Air Service airplanes repurposed for civil use.

The first commercial passenger transport seaplane business was founded in 1923 as a puddle jumper service between the Channel Islands between the U.K. and France. Soon after, wealthy residents of New York State's Long Island region began riding commercial seaplanes as their daily commute between their homes on the affluent North Short to their offices on Wall Street in Manhattan via the East and Hudson Rivers.

Across the ocean in Germany, the Dornier Do X became the largest, heaviest commercial airliner ever to fly in July 1929. The largest airplane in the United Kingdom at that time, the Short Sarafand, was also a flying boat with a biplane wing configuration, first flying in 1932. By 1939, the Boeing 314 Clipper monoplane took to the skies for the first time.

Based in part on the failed XB-15 heavy bomber prototype and one of the first flagship airplanes of the Pan Am airline, the Clipper flying boat paved the way for the iconic 707 and 747. Doing so by helping to generate the revenue Boeing needed to be able to innovate. Of course, building a fair percent of every American Second World War strategic bomber of significance also helped tremendously.

The U.S. Army Air Corps even managed to fit a pair of pontoons underneath a Grumman F4F Wildcat and a Douglas C-47 Skytrain for a trial run during this time. The Axis did a very similar test with the Japanese A6M Zero among a host of Imperial Japanese floatplanes. But with the war's conclusion in 1945, the era of dominance by seaplanes was well and truly finished.

Years of warfare taught militaries and civilians alike how to build large land-based airfields in relatively short periods. More powerful aero engines that could take off at shorter distances meant the smoothness of a tarmac takeoff quickly rendered sea planes largely obsolete. A handful last hurrahs came from the British Saunders-Roe Princess turboprop airliner and the positively colossal American Hughes H-4 Hercules-Spruce Goose. The Martin JRM Mars also deserves a mention in this time period, among a few other outliers.

The Hughes H-4 specifically, was the largest airplane ever flown for a staggering period between 1947 and 2019. Today, only a handful of companies globally produce flying boats. Almost all turboprop cargo transports, most often built in either China, Japan, or Canada. As for their seaplane cousin float planes, they're almost strictly the domain of small private airplanes like Cessnas, with a few exceptions.

Check back soon for more from Sea Month here on autoevolution.