The European Union wants to curb early obsolescence and greenwashing. The idea is to give customers better means to select products that are really aligned with their environmental concerns. Although this need did not emerge from car buyers, the auto industry is probably the best one to kick off a deep change in how we run the economy and care for the planet. For the sake of both, we should kill planned obsolescence as soon as possible – in all economy segments that apply it.

If you are not familiar with the concept, it is frequently attributed to Alfred P. Sloan. The long-time GM CEO suggested model-year changes in the 1920s to make customers desire “something a little newer, a little better, a little sooner than is necessary," as Brooke Stevens would define planned obsolescence in the 1950s.

The commercial strategy is as simple as it is brilliant. The issue is that its foundation was reckless. Economic success was and still is defined as producing and selling increasingly more goods to obtain maximum profits. Sloan is famous for having coined a defining motto for the automotive industry. In his book “My Years With General Motors,” he said General Motors existed not to make cars: it was born to make money making cars.

There are famous stories of companies that created products so durable that they eventually went bankrupt. As their merchandise would not break, people would buy them only once and use them for a lifetime – sometimes, more than one, as it happened with Wallig stoves in Brazil, for example. Each country must know at least one similar story.

This was what Sloan tried to prevent: sales stagnation. Ironically, the idea was not his. He just applied something the bike industry was using at the time. If GM cars presented improvements, even if small ones, that could convince customers to trade their old rides for those on dealership lots. After the idea was tried with bicycles and cars, it worked with everything else.

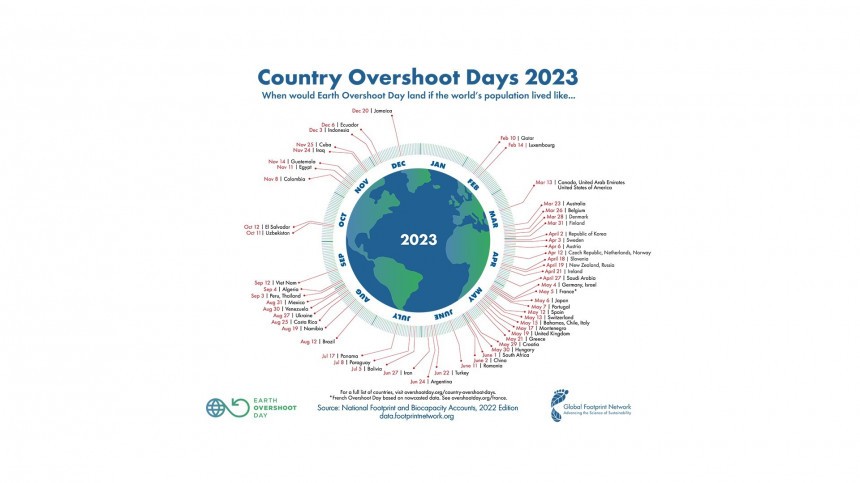

The problem is that most companies now depend on selling more of whatever they make in a world with limited resources. Low-profit goods need even higher sales volumes to prove they can make money. Earth Overshoot Day was created because of that, and it demonstrates how extreme this has become. Every year, the day in which we spend all the raw materials and resources the planet can generate annually arrives earlier. The population is also growing, and more people have access to modern-life comforts, which explains the need for higher production numbers. Planned obsolescence makes that scenario worse. One hundred years ago, it may have seemed it made sense, but not anymore.

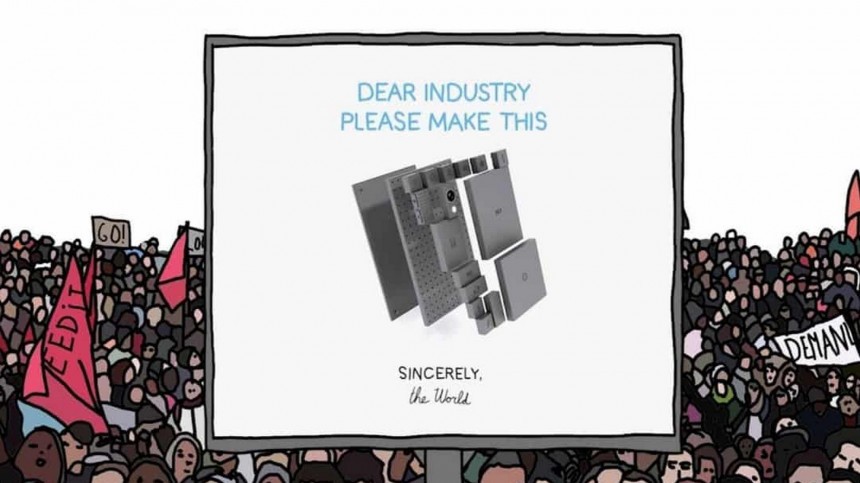

Putting this strategy to rest is already happening in some industries, even if still in baby steps. In 2014, I wrote about two companies that were trying to change the business models we follow in their respective market segments. One was Riversimple – an automotive startup I have often talked about here – and the other was Phonebloks.

The latter proposed to create a modular and upgradeable smartphone. It would allow users to buy different modules for specific tasks, such as one for better pictures, larger batteries for more autonomy, a better screen, 5G capability instead of 4G, and so forth. If a module broke or had issues, you would not have to throw everything away in the recycling bin: you’d just replace what wasn’t working or needed an upgrade. Google liked the idea and started Project Ara. Sadly, it did not move forward with it.

The good news is that other companies liked the concept and developed it in different industries. The best example nowadays comes from Framework. It started its activities with a modular laptop, and it is now expanding to more uses. The company incentivizes developers to come up with new ideas for its laptop modules, which makes them go beyond their original application. One recent example is a case for the mainboard that helped create a portable desktop computer.

While we have these isolated initiatives, people still have to fight for the right to repair in several American states and also in Europe. They need more than only being able to have something fixed instead of replaced: the products they buy must also have been conceived to be repaired, which is not always the case.

Sometimes, the merchandise is designed so that servicing is not economically feasible. Either the repair itself or the damaged component replacement – when that is possible – is so expensive compared to the product’s costs that it is just not worth it. If anything breaks, just buy a new one: that’s the motto. Weirdly, the automaker that claims that curbing climate change is its primary mission has several examples of these harmful practices.

On March 15, Reuters said Tesla was sued by two different class actions under accusations that the company was “unlawfully curbing competition for maintenance and replacement parts for its electric vehicles.” The lawsuits allege that this forces its customers to go to Tesla Service Center to have their vehicles fixed at higher prices than independent shops would charge. And this is just one example of all the EV maker’s attitudes against the right to repair.

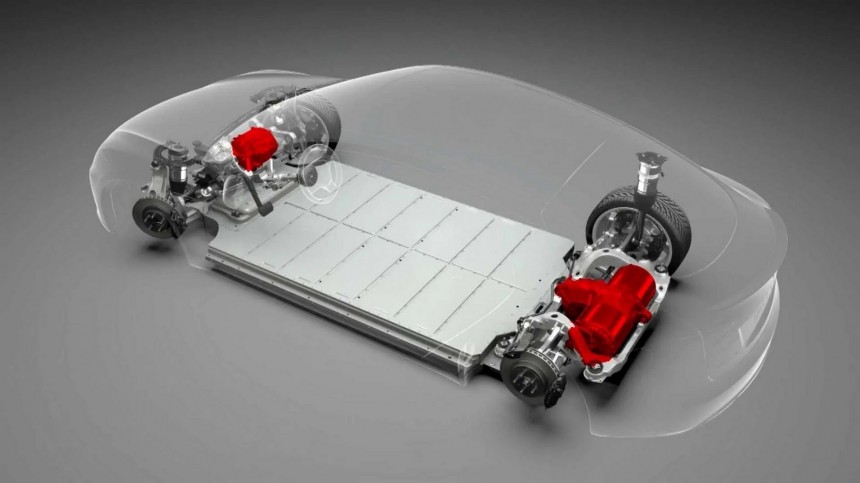

In November 2020, Tesla recommended its customers in Massachusetts vote against a right-to-repair bill. It did not work: the bill passed by a landslide. Finally, the EV maker’s battery packs demand a lot of work to service, which makes it just replace them and charge its customers $15,000 to more than $20,000 – depending on the component capacity.

For the record, Tesla does that with several car subsystems. It almost charged Jennifer Sensiba with replacing an entire second-row seat assembly because her dog puked on the seat belt clickers during a test drive. Tesla Service Centers are not equipped to remove just the clickers, and any repair in these seats demands removing the whole assembly – or replacing it, as technicians told Sensiba it could be the case. Although that would be pretty expensive – around $4,000, from what I have heard – it does not compare to battery pack issues.

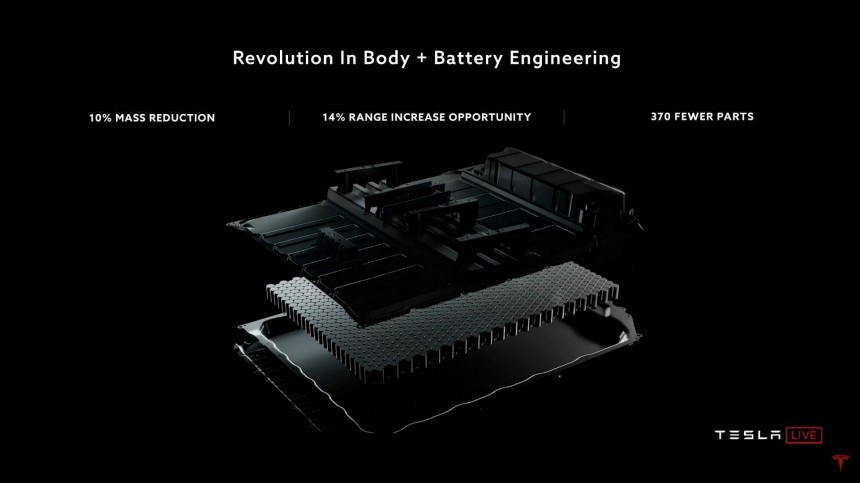

According to Sandy Munro, the new 4680 structural battery pack in the Model Y is not repairable. If you have any issue with it, you just dump the whole thing into a shredder to recover the raw materials.

Well, the EU wants that to end. The European Parliament voted to blacklist seven common practices described by the European Environment Bureau (EEB). Four of them have to do with planned obsolescence, and three with greenwashing, defined as presenting something as more environmentally responsible than it actually is.

Saying that a product or service is carbon-neutral has become a fever among several companies – regardless of dealing with food or automobiles. What the EU ruled is that no enterprise can claim that because carbon neutrality can only be achieved collectively. It is perfectly fine if you get the idea and still do not agree with EEB’s absolute definition of what this concept means. After all, what those bragging about carbon neutrality are saying is that they do not help put more carbon in the atmosphere, so it is mostly semantics.

EEB’s argument is that most of these claims are not based on the production process or anything like it. According to that bureau, a large portion relies on buying carbon credits, some of which are proving to be worthless. The EEB is also unhappy with claims to reach carbon neutrality in the future without concrete plans to back them up.

The way the EU found to try to fix that was by forbidding unsubstantiated claims – future or present. The only exception is getting them through strict certification processes such as EU Ecolabel. In other words, companies will have to prove they are serious about any measures they take or intend to in order to fight climate change. Summing that up, no more cheap talk or empty promises.

Regarding planned obsolescence, the EU does not want industries building anything with weak parts that will eventually force the products to be replaced. It also does not want over-the-air (OTA) updates turning these products into useless machines. Blocking self-repairs or third parties from performing them is also on the blacklist. Finally, the EU does not want companies charging unreasonable prices for components which could make repairing the product not worth it. From what you have read so far, you can already see this will cause some issues in the EU.

Remember how much Tesla charges for a battery pack replacement? Nissan also had cases of charging around €20,000 or even $35,000 for LEAF battery packs. Honestly, any BEV manufacturer will eventually face a similar situation. It is inherent to how these vehicles are designed, with a massive battery pack. How can the EU promote battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and ban combustion engines while ruling companies can’t sell repair parts so expensive that this will make the products impossible to fix? Again, battery packs are prohibitively costly, and there is no way to reduce their prices as they are.

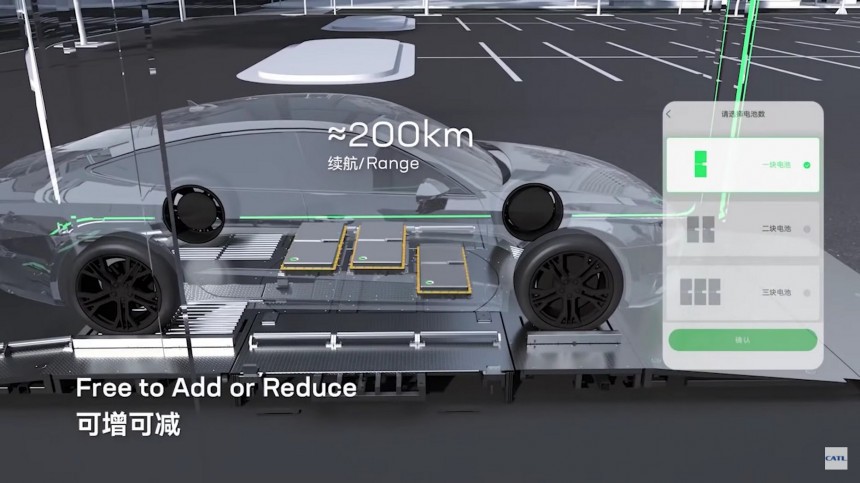

One way to solve that would be to use battery modules – just like the Choco-SEBs CATL created – and not a large battery pack. If any module presents problems, replacing it will be much cheaper than the whole pack, as it is often necessary today. It will be more complex than dealing with a single part, but how good is this solution when a failure may kill the entire car?

Brand-new EVs are being totaled even if they only get scratches in their battery packs: insurance companies complain they cannot determine if it is still safe to use them or not. Being so expensive, insurers have no other option but just to write off the BEVs and give their owners a check. If the only issue with these cars happens to be the battery pack, sending them to junkyards is the opposite of sustainability.

It will be interesting to see how the EU will solve this paradox. How will it force the BEVs we have today to comply with its new rules on planned obsolescence? How will it deal with Tesla and its notorious aversion to the right to repair? If there is any vehicle that deserves to live for decades considering its environmental impact, it is the electric car. Yet, it will not do so with the current battery technology and even in the way they are evolving.

This story does not end without its most refined irony. If BEVs are not easily repairable, how green are they? If the idea is to produce millions and to replace them more frequently than we replace ICE cars, how sustainable is that? Isn’t that the very definition of greenwashing? The European Parliament will have a lot to discuss – as will all other legislators around the world. A shift to electric motors that preserves planned obsolescence is just a different way to keep everything the same.

The commercial strategy is as simple as it is brilliant. The issue is that its foundation was reckless. Economic success was and still is defined as producing and selling increasingly more goods to obtain maximum profits. Sloan is famous for having coined a defining motto for the automotive industry. In his book “My Years With General Motors,” he said General Motors existed not to make cars: it was born to make money making cars.

This was what Sloan tried to prevent: sales stagnation. Ironically, the idea was not his. He just applied something the bike industry was using at the time. If GM cars presented improvements, even if small ones, that could convince customers to trade their old rides for those on dealership lots. After the idea was tried with bicycles and cars, it worked with everything else.

Putting this strategy to rest is already happening in some industries, even if still in baby steps. In 2014, I wrote about two companies that were trying to change the business models we follow in their respective market segments. One was Riversimple – an automotive startup I have often talked about here – and the other was Phonebloks.

The good news is that other companies liked the concept and developed it in different industries. The best example nowadays comes from Framework. It started its activities with a modular laptop, and it is now expanding to more uses. The company incentivizes developers to come up with new ideas for its laptop modules, which makes them go beyond their original application. One recent example is a case for the mainboard that helped create a portable desktop computer.

Sometimes, the merchandise is designed so that servicing is not economically feasible. Either the repair itself or the damaged component replacement – when that is possible – is so expensive compared to the product’s costs that it is just not worth it. If anything breaks, just buy a new one: that’s the motto. Weirdly, the automaker that claims that curbing climate change is its primary mission has several examples of these harmful practices.

In November 2020, Tesla recommended its customers in Massachusetts vote against a right-to-repair bill. It did not work: the bill passed by a landslide. Finally, the EV maker’s battery packs demand a lot of work to service, which makes it just replace them and charge its customers $15,000 to more than $20,000 – depending on the component capacity.

According to Sandy Munro, the new 4680 structural battery pack in the Model Y is not repairable. If you have any issue with it, you just dump the whole thing into a shredder to recover the raw materials.

Saying that a product or service is carbon-neutral has become a fever among several companies – regardless of dealing with food or automobiles. What the EU ruled is that no enterprise can claim that because carbon neutrality can only be achieved collectively. It is perfectly fine if you get the idea and still do not agree with EEB’s absolute definition of what this concept means. After all, what those bragging about carbon neutrality are saying is that they do not help put more carbon in the atmosphere, so it is mostly semantics.

The way the EU found to try to fix that was by forbidding unsubstantiated claims – future or present. The only exception is getting them through strict certification processes such as EU Ecolabel. In other words, companies will have to prove they are serious about any measures they take or intend to in order to fight climate change. Summing that up, no more cheap talk or empty promises.

Remember how much Tesla charges for a battery pack replacement? Nissan also had cases of charging around €20,000 or even $35,000 for LEAF battery packs. Honestly, any BEV manufacturer will eventually face a similar situation. It is inherent to how these vehicles are designed, with a massive battery pack. How can the EU promote battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and ban combustion engines while ruling companies can’t sell repair parts so expensive that this will make the products impossible to fix? Again, battery packs are prohibitively costly, and there is no way to reduce their prices as they are.

Brand-new EVs are being totaled even if they only get scratches in their battery packs: insurance companies complain they cannot determine if it is still safe to use them or not. Being so expensive, insurers have no other option but just to write off the BEVs and give their owners a check. If the only issue with these cars happens to be the battery pack, sending them to junkyards is the opposite of sustainability.

It will be interesting to see how the EU will solve this paradox. How will it force the BEVs we have today to comply with its new rules on planned obsolescence? How will it deal with Tesla and its notorious aversion to the right to repair? If there is any vehicle that deserves to live for decades considering its environmental impact, it is the electric car. Yet, it will not do so with the current battery technology and even in the way they are evolving.

This story does not end without its most refined irony. If BEVs are not easily repairable, how green are they? If the idea is to produce millions and to replace them more frequently than we replace ICE cars, how sustainable is that? Isn’t that the very definition of greenwashing? The European Parliament will have a lot to discuss – as will all other legislators around the world. A shift to electric motors that preserves planned obsolescence is just a different way to keep everything the same.