Sometime in the first few months of 2022, NASA will be launching the most powerful rocket ever made, carrying with it the most advanced spaceship humans ever created. The mission is called Artemis I, and it marks the beginning of the second lunar exploration program of our species and, hopefully, the start of humanity’s expansion into the solar system.

With the preparation of both the Space Launch System rocket and Orion capsule in their final stages, NASA has begun taking a deeper look into how the entire make-it-or-break-it mission is supposed to go. Sure, it’s a dry run, with no actual humans on board, and with the ship meant just to circle the Moon and come back, but it is one that will let us know if everything is ready and safe for humans to begin their exploration efforts.

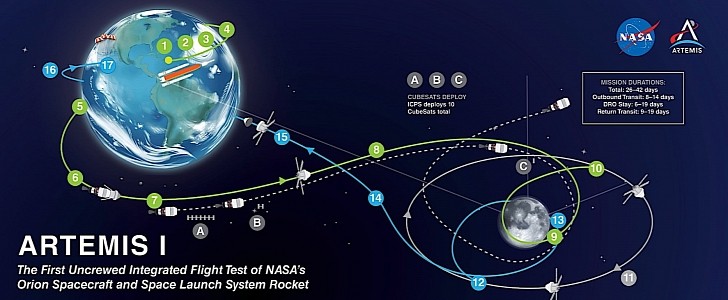

To help us all get a better understanding of how the Artemis I mission is going to go, NASA released some time ago something it calls the Artemis I map. We dusted it off from the agency's archives and brought it back into focus as, in theory, only four months now separate us from the historic flight.

As a side note, before we dive into it, remember these are pretty much the same steps all subsequent Artemis missions to the Moon will have to go through (plus the actual landing), so take notes if you plan on really understanding how this goes.

As said, Artemis I is the first integrated flight test of the SLS-Orion combo. Like most other historic space missions, it would take its first step, the launch, from Launch Complex 39B at the Kennedy Space Center – that's from where Apollo missions departed for the Moon.

SLS will lift the Orion thanks to the immense power provided by the core stage and two solid rocket boosters. Once the needed altitude is reached, the SLS becomes useless, and this is where the second step comes in, the jettison of the rocket, boosters, fairings, and launch abort system.

The cutoff and separation of the core stage will take place, and the Orion will be on its own, in Earth orbit. This is where a perigee raise maneuver meant to place the capsule into position comes in.

Up next is the systems check and solar panel adjustments, operations that take place while the Orion is still circling Earth. If everything checks out, mission control down at the Kennedy Space Center will move to a trans-lunar injection (TLI) burn of the Orion’s engines.

This procedure should take about 20 minutes, and will put the spaceship on a course to the Moon. After the ship is committed, interim cryogenic propulsion stage (ICPS) separation and disposal take place.

Next on the list are outbound trajectory correction (OTC) burns, conducted as necessary to steer the capsule to its target. Then comes the actual flight to the satellite, something NASA calls outbound powered flyby (OPF). The flight should take Orion to within 60 nautical miles from the surface, opening the doors for orbit insertion.

After this is achieved, the ship will perform something called distant retrograde orbit (DRO), moving around the Moon one and a half times at a distance of 38,000 nautical miles. Once the orbits are completed, Orion will start heading back to Earth by performing something called return powered flyby (RPF).

On the way back, as it did on the way out, the ship will probably have to perform return trajectory correction (RTC) burns to keep it aimed at our planet.

As it approaches Earth, Orion will split, separating the crew module from the service one. The crew module will enter the Earth’s atmosphere (something NASA calls EI, or Earth Interface) and splash down in the Pacific Ocean, from where it will be recovered by the U.S. Navy. The entire mission duration is estimated at between 26 to 42 days, which is a hell of a lot more than Apollo.

And that’s how you make space exploration history. In a more compact way, the entire mission should go a bit like this:

Launch – drop boosters – drop core stage – perigee raise maneuver – in-orbit systems checks – lunar injection burn – cryogen stage separation – trip to the moon – lunar orbit insertion – spin around the Moon – leave Moon orbit – make trip back – adjust course as needed – separate crew module – enter atmosphere – splashdown – get saved.

Or, if you prefer acronyms:

Launch – drop boosters – drop core stage - perigee raise maneuver – in-orbit systems checks – TLI – ICPS – OTC – OPF – DRO – DRO – RPF – RTC - separate crew module – EI – splashdown - get saved.

To help us all get a better understanding of how the Artemis I mission is going to go, NASA released some time ago something it calls the Artemis I map. We dusted it off from the agency's archives and brought it back into focus as, in theory, only four months now separate us from the historic flight.

As a side note, before we dive into it, remember these are pretty much the same steps all subsequent Artemis missions to the Moon will have to go through (plus the actual landing), so take notes if you plan on really understanding how this goes.

As said, Artemis I is the first integrated flight test of the SLS-Orion combo. Like most other historic space missions, it would take its first step, the launch, from Launch Complex 39B at the Kennedy Space Center – that's from where Apollo missions departed for the Moon.

The cutoff and separation of the core stage will take place, and the Orion will be on its own, in Earth orbit. This is where a perigee raise maneuver meant to place the capsule into position comes in.

Up next is the systems check and solar panel adjustments, operations that take place while the Orion is still circling Earth. If everything checks out, mission control down at the Kennedy Space Center will move to a trans-lunar injection (TLI) burn of the Orion’s engines.

This procedure should take about 20 minutes, and will put the spaceship on a course to the Moon. After the ship is committed, interim cryogenic propulsion stage (ICPS) separation and disposal take place.

After this is achieved, the ship will perform something called distant retrograde orbit (DRO), moving around the Moon one and a half times at a distance of 38,000 nautical miles. Once the orbits are completed, Orion will start heading back to Earth by performing something called return powered flyby (RPF).

On the way back, as it did on the way out, the ship will probably have to perform return trajectory correction (RTC) burns to keep it aimed at our planet.

As it approaches Earth, Orion will split, separating the crew module from the service one. The crew module will enter the Earth’s atmosphere (something NASA calls EI, or Earth Interface) and splash down in the Pacific Ocean, from where it will be recovered by the U.S. Navy. The entire mission duration is estimated at between 26 to 42 days, which is a hell of a lot more than Apollo.

Launch – drop boosters – drop core stage – perigee raise maneuver – in-orbit systems checks – lunar injection burn – cryogen stage separation – trip to the moon – lunar orbit insertion – spin around the Moon – leave Moon orbit – make trip back – adjust course as needed – separate crew module – enter atmosphere – splashdown – get saved.

Or, if you prefer acronyms:

Launch – drop boosters – drop core stage - perigee raise maneuver – in-orbit systems checks – TLI – ICPS – OTC – OPF – DRO – DRO – RPF – RTC - separate crew module – EI – splashdown - get saved.