Ground effects were first implemented in Formula One by Lotus designer Colin Chapman. In a time when equalizing the performances of F1 engines was not an option – in the 1970s that is – the teams using Cosworth power plants were trying to find a viable solution to make up for the loss in performances as compared to richer F1 manufacturers. And maximizing the power of their engines through some clever aerodynamics was the only way they knew how.

The term “ground effects” was given to the innovatory aerodynamic package created to set up a sucking-like effect under an F1 car when cornering. What that means is that F1 machineries were practically “glued” to the track through some rather interesting under-car styling, leading to out-of-this-world cornering speeds.

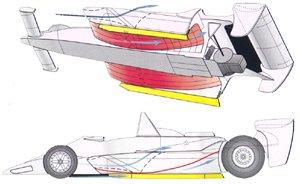

The principle behind the ground effect is quite simple. What the F1 engineers tried to obtain was a low pressure area beneath the car which, combined with the high pressure above it, would create a tremendous force pushing the car downwards. In Formula One, the solution found by Chapman was to create a revolutionary design for the car's underside. It's curved styling – like inverted airfoils – allowed the air that entered the car's underbody to accelerate through a narrow mid-section between the car and the ground, therefore creating a low-pressure section.

However, the aforementioned design was not enough to create the expected ground effect, as the air coming from both sides of the car (from underneath) would have ruined the entire vacuum effect. In order to prevent that from happening, the Lotus engineers fitted the cars with flexible side skirts, therefore sealing its underside section. While initially built out of brushes or plastic, the best solution proved to be rubber-build skirts, as they didn't wear out during races.

Colin Chapman – with the help of fellow engineers Peter Wright and Tony Rudd – developed the entire concept through the 1976 season and eventually implemented it on the famous Lotus 78 (also known as the John Player Special Mk III) starting the 1977 Argentine Grand Prix.

Like all starts, however, the 1977-build Lotus 78 suffered from several reliability problems. First of all, the airflow coming from beneath the car interacted with the large rear wing, causing plenty of drag at high speeds. What practically happened was that all the advantage gained at corners was counteracted by the poor performances of the Cosworth engines in straight line. The next step, made by Ford, was to try and improve the performances of their V8 powerplant. However, race to race adjustments on the engine often led to poor reliability, and the season ended with no less than 5 engine failures for 2nd placed Mario Andretti.

The next season was going to be one for the books for Lotus, as the team managed to make all the necessary adjustments over the winter, including a new design for the rear wing for the newly-developed Lotus 79. The Lotus 78 took one more win in 1978, after which it was replaced by the more effective 79 model. With it, the team powered to 7 more wins in the series, a world class dominance that led to both drivers' (Andretti) and manufacturers' titles that year.

The season ended in tragedy for the Lotus team, though, as Ronnie Peterson died of complications following a crash in the 1978 Italian Grand Prix. Having damaged his Lotus 79 in the practice sessions, Peterson was sent to race on Sunday with a poor-developed version of the 78 model. He was caught in a start line incident during the Italian race, with his 78 hitting the barriers in the process.

Trying to challenge the Lotus 79 for championship wins in 1978 was another ingenious car, this time developed by Gordon Murray, the Brabham BT46B. Murray, however, decided to use a different working principle in order to create the vacuum effect underneath the car – as the Alfa Romeo engines that powered the BT46 were too wide to permit such an underside designs as the Lotus 79 – by using a giant fan in the rear of the car. Taking the example of the Chaparral 2J “sucker” sports car in 1970, Murray fitted a fan in the rear of the car that was powered by the engine itself. The faster the engine ran, the more air was sucked by the fan from the underside of the car, creating the aforementioned effect. Just like Chapman at Lotus, the BT46B was fitted with side skirts to maintain a low pressure section underneath it, without exterior alterations.

As moveable aerodynamic devices were banned by F1's ruling body, Murray argued the use of the fan by its cooling function. While working as an air-sucking device, the fan was also used to assist engine cooling, as it drew air from the radiator. And that was perfectly legal.

When Lotus' Chapman realized what was going on, he began working on a “fancar” himself. However, during the course of the same year, Brabham owner Bernie Ecclestone decided to take the car out of the series in order to avoid a conflict with the other teams, with FIA later labeling the fan used by the BT46B as a “moveable aerodynamic device” and therefore banning it for good. Hadn't it been for that ban, it would have been quite a fight between the Lotus 79 and the Brabham BT46B for the 1979 World Championship.

Due to the increased level of cornering speeds in Formula One during the 1979 season – which led to lap times some 6 seconds quicker than in previous years – the FIA decided to introduce a mandatory flat underside for the F1 cars. However, the rules stated that the underneath side of the car should be flat (only) at the pits. It was the same Gordon Murray to come up with an innovative solution to counteract that rule, as he invented a device that would automatically lower his Brabham BT49 when on the track.

So basically, the cars at the pits were as legal as sunshine, while suddenly becoming illegal as soon as they left the pit lane. It wasn't for long that other F1 engineers realized what was going on and, by mid-1981, all cars were built after the same concept. The side skirts ban was practically useless, with the FIA finally realizing it at the end of 1981. By that time, they had no other choice by to declare the devices legal again.

As the upcoming season would prove, that was to be a rather uninspired decision by the FIA. Due to some of the teams using powerful turbocharged engines, it soon became unbearable for the drivers to resist the high temperatures and the quick cornering speeds. A series of incidents/accidents (namely Nelson Piquet fainting on the podium of the Brazilian GP after an exhausting race, the death of Ferrari's Gilles Villeneuve, Rene Arnoux’s Renault being projected into the tire barriers due to ground effect pressure, Jochen Mass's burning car was sent into the crowd because of the same pressure, Didier Pironi's accident during the German Grand Prix) finally triggered a quick response from the FISA, with the ruling body deciding to ban ground effects in the final stages of the 1983 season.

The term “ground effects” was given to the innovatory aerodynamic package created to set up a sucking-like effect under an F1 car when cornering. What that means is that F1 machineries were practically “glued” to the track through some rather interesting under-car styling, leading to out-of-this-world cornering speeds.

The principle behind the ground effect is quite simple. What the F1 engineers tried to obtain was a low pressure area beneath the car which, combined with the high pressure above it, would create a tremendous force pushing the car downwards. In Formula One, the solution found by Chapman was to create a revolutionary design for the car's underside. It's curved styling – like inverted airfoils – allowed the air that entered the car's underbody to accelerate through a narrow mid-section between the car and the ground, therefore creating a low-pressure section.

However, the aforementioned design was not enough to create the expected ground effect, as the air coming from both sides of the car (from underneath) would have ruined the entire vacuum effect. In order to prevent that from happening, the Lotus engineers fitted the cars with flexible side skirts, therefore sealing its underside section. While initially built out of brushes or plastic, the best solution proved to be rubber-build skirts, as they didn't wear out during races.

Colin Chapman – with the help of fellow engineers Peter Wright and Tony Rudd – developed the entire concept through the 1976 season and eventually implemented it on the famous Lotus 78 (also known as the John Player Special Mk III) starting the 1977 Argentine Grand Prix.

Like all starts, however, the 1977-build Lotus 78 suffered from several reliability problems. First of all, the airflow coming from beneath the car interacted with the large rear wing, causing plenty of drag at high speeds. What practically happened was that all the advantage gained at corners was counteracted by the poor performances of the Cosworth engines in straight line. The next step, made by Ford, was to try and improve the performances of their V8 powerplant. However, race to race adjustments on the engine often led to poor reliability, and the season ended with no less than 5 engine failures for 2nd placed Mario Andretti.

The next season was going to be one for the books for Lotus, as the team managed to make all the necessary adjustments over the winter, including a new design for the rear wing for the newly-developed Lotus 79. The Lotus 78 took one more win in 1978, after which it was replaced by the more effective 79 model. With it, the team powered to 7 more wins in the series, a world class dominance that led to both drivers' (Andretti) and manufacturers' titles that year.

The season ended in tragedy for the Lotus team, though, as Ronnie Peterson died of complications following a crash in the 1978 Italian Grand Prix. Having damaged his Lotus 79 in the practice sessions, Peterson was sent to race on Sunday with a poor-developed version of the 78 model. He was caught in a start line incident during the Italian race, with his 78 hitting the barriers in the process.

Trying to challenge the Lotus 79 for championship wins in 1978 was another ingenious car, this time developed by Gordon Murray, the Brabham BT46B. Murray, however, decided to use a different working principle in order to create the vacuum effect underneath the car – as the Alfa Romeo engines that powered the BT46 were too wide to permit such an underside designs as the Lotus 79 – by using a giant fan in the rear of the car. Taking the example of the Chaparral 2J “sucker” sports car in 1970, Murray fitted a fan in the rear of the car that was powered by the engine itself. The faster the engine ran, the more air was sucked by the fan from the underside of the car, creating the aforementioned effect. Just like Chapman at Lotus, the BT46B was fitted with side skirts to maintain a low pressure section underneath it, without exterior alterations.

As moveable aerodynamic devices were banned by F1's ruling body, Murray argued the use of the fan by its cooling function. While working as an air-sucking device, the fan was also used to assist engine cooling, as it drew air from the radiator. And that was perfectly legal.

When Lotus' Chapman realized what was going on, he began working on a “fancar” himself. However, during the course of the same year, Brabham owner Bernie Ecclestone decided to take the car out of the series in order to avoid a conflict with the other teams, with FIA later labeling the fan used by the BT46B as a “moveable aerodynamic device” and therefore banning it for good. Hadn't it been for that ban, it would have been quite a fight between the Lotus 79 and the Brabham BT46B for the 1979 World Championship.

Due to the increased level of cornering speeds in Formula One during the 1979 season – which led to lap times some 6 seconds quicker than in previous years – the FIA decided to introduce a mandatory flat underside for the F1 cars. However, the rules stated that the underneath side of the car should be flat (only) at the pits. It was the same Gordon Murray to come up with an innovative solution to counteract that rule, as he invented a device that would automatically lower his Brabham BT49 when on the track.

So basically, the cars at the pits were as legal as sunshine, while suddenly becoming illegal as soon as they left the pit lane. It wasn't for long that other F1 engineers realized what was going on and, by mid-1981, all cars were built after the same concept. The side skirts ban was practically useless, with the FIA finally realizing it at the end of 1981. By that time, they had no other choice by to declare the devices legal again.

As the upcoming season would prove, that was to be a rather uninspired decision by the FIA. Due to some of the teams using powerful turbocharged engines, it soon became unbearable for the drivers to resist the high temperatures and the quick cornering speeds. A series of incidents/accidents (namely Nelson Piquet fainting on the podium of the Brazilian GP after an exhausting race, the death of Ferrari's Gilles Villeneuve, Rene Arnoux’s Renault being projected into the tire barriers due to ground effect pressure, Jochen Mass's burning car was sent into the crowd because of the same pressure, Didier Pironi's accident during the German Grand Prix) finally triggered a quick response from the FISA, with the ruling body deciding to ban ground effects in the final stages of the 1983 season.